Common Pulmonary Diseases in Dogs

Douglas Palma, DVM, DACVIM (SAIM), The Animal Medical Center, New York, New York

What should I know about common canine pulmonary diseases?

Pulmonary disease is a common cause of respiratory signs in dogs. A thorough history and examination help localize the pulmonary parenchyma rather than other parts of the respiratory system. Signalment, clinical onset and progression, geographic location, and additional organ involvement can help prioritize differential diagnoses.

Patients with pulmonary disease may exhibit coughing, increased respiratory rate, dyspnea, and/or exercise intolerance. Depending on cause and nonrespiratory involvement, nonspecific clinical signs (eg, lethargy, inappetence, weight loss) may be present. Many patients may have a mixed pattern of breathing characterized by increased inspiratory and expiratory effort, as the disease processes may involve concurrent airway obstruction and altered lung compliance. Therefore, a pure restrictive (decreased tidal volume, increased respiratory rate) or obstructive (increased expiratory effort) pattern of breathing is often not observed.

The following are pulmonary diseases frequently encountered in dogs.

Bacterial Pneumonia

Pneumonia may be community-acquired (ie, characterized by bronchopneumonia in a dog with a history of being housed in the community) or secondary to altered pulmonary defenses, aspiration, or hematogenous infection.

Community-acquired pneumonia is most common in young dogs and in dogs with recent exposure to kennels or shelters.1 Exposure to other dogs makes Bordetella bronchiseptica most common, but other opportunistic pathogens may be involved.1 Streptococcus zooepidemicus, another emerging bacterial pathogen, is associated with development of hemorrhagic pneumonia.2

Aspiration pneumonia is more common in older patients. Clinical history is important to help identify potential underlying causes. The most commonly reported causes of aspiration pneumonia in dogs include esophageal disease, vomiting, neurologic disorders, laryngeal disease, and postanesthetic aspiration.3 Opportunistic infections complicate the initial aspiration event. A mixed population of bacteria with an anaerobic population is common. Aspiration pneumonia is typically characterized by a distribution to the most dependent lung lobe (ie, right middle). However, distribution to any lung or multiple lungs is possible.4 Although respiratory signs may be present, many older patients are clinically silent; pneumonia must be considered in dogs with nonspecific signs of lethargy, inappetence, and/or fatigue.

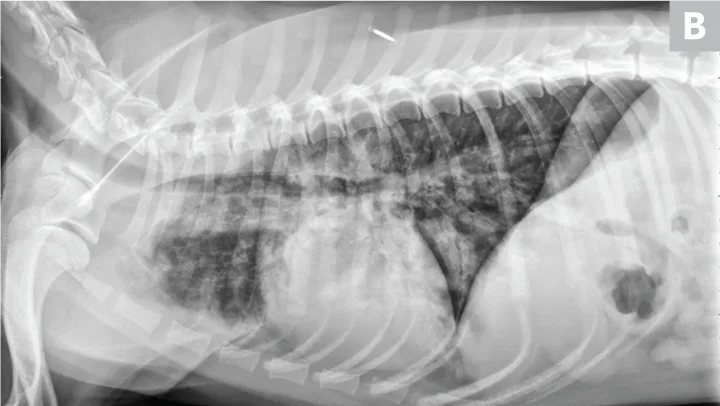

Dogs with bacterial pneumonia are typically presented with acute-onset coughing, lethargy, inappetence, and/or respiratory distress. An inflammatory leukogram and pyrexia, although common, are not always present. Radiographs may reveal an interstitial-to-alveolar pattern with a cranioventral distribution (Figure 1). Atypical distributions can also occur.5

(A) Bronchopneumonia. Cranioventral distribution of alveolar disease with air bronchograms. (B) A patchy distribution can be observed on the lateral projection. The changes overlying the heart may be missed in subtle cases.

Culture-directed therapy is ideal; however, empiric treatment with knowledge of common organisms is reasonable.6 Multidrug-resistant organisms are more common following recent antibiotic exposure.7,8

Viral Pneumonia

Viral pneumonia is generally associated with canine distemper virus (CDV) or canine influenza virus (CIV). Emerging viral pathogens (eg, canine pantropic coronavirus, canine pneumovirus) have recently been described.9 Canine herpes-virus can, albeit rarely, induce interstitial pneumonia.10,11

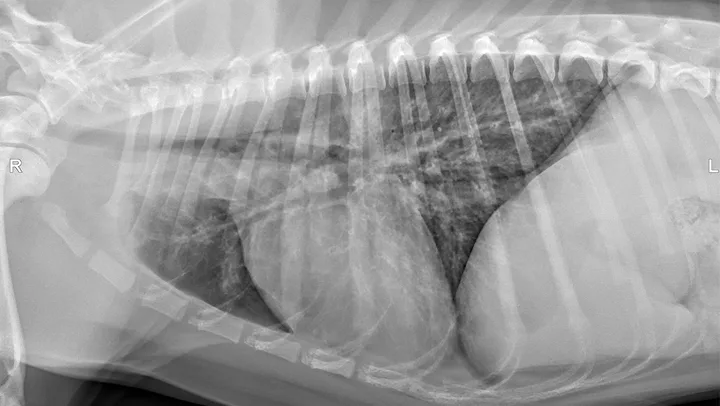

CDV should be suspected in poorly vaccinated dogs with multiorgan involvement. Dogs with CDV may have exhibited only respiratory signs before developing characteristic nonrespiratory signs.12 Radiographs may reveal a diffuse interstitial pattern (Figure 2). Diagnosis is supported by compatible clinical signs and complementary diagnostic testing (ie, real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction [RT-PCR], serology, CSF pleocytosis). Conjunctival scraping and tissue-based immunohistochemistry may confirm diagnosis.

CDV pneumonia with a diffuse interstitial pattern confirmed by multisystemic signs, urine RT-PCR, and necropsy

CIV may involve the pulmonary parenchyma and is often complicated by opportunistic bacteria. Patients typically are presented with lethargy, anorexia, nasal discharge, and coughing. PCR of the nasal cavity or oropharynx within 3 to 5 days of infection may confirm organism presence. Patients with clinical signs lasting longer than 5 days may require serologic testing.13

Fungal Pneumonia

The incidence of fungal disease varies widely by geographic region. Dogs with fungal pneumonia are generally young and exhibit signs of generalized illness (eg, lethargy, weight loss, pyrexia, decreased appetite). Many patients with pulmonary involvement do not show respiratory signs; coughing and respiratory distress are most common among those that do.14-16 Additional organ systems (eg, dermatologic, GI, ocular, musculoskeletal) may be affected.17

Blood testing is somewhat nonspecific. Common abnormalities include hypoalbuminemia, hyperglobulinemia, nonregenerative anemia, and monocytosis; hypercalcemia and eosinophilia are less common. An inflammatory leukogram may be observed. Radiographs often show a miliary pattern and may show hilar lymphadenopathy. A combination of serologic and antigen testing may support diagnosis. Cytology or tissue histopathology may identify the organism.18-21

Eosinophilic Bronchopneumopathy

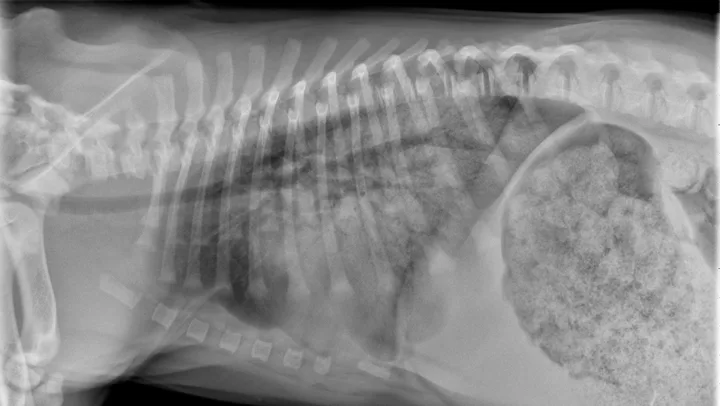

Eosinophilic bronchopneumopathy (EB) is an idiopathic inflammatory hypersensitivity disorder associated with acute onset coughing, gagging, retching, and/or respiratory distress. Radiographs may reveal a diffuse bronchointerstitial pattern or alveolar disease (Figure 3). Patients with EB have airway cytology supportive of eosinophilic inflammation and are negative for parasitic testing.

Eosinophilic bronchopneumopathy. Note the heavy, patchy bronchointerstitial pattern.

EB’s acute nature, occurrence in young animals, and radiographic findings may mimic pneumonia. EB should be suspected in patients that fail treatment for pneumonia, have peripheral eosinophilia, or have uncharacteristically severe diffuse bronchointersitial patterns; further diagnostic investigation is indicated to confirm eosinophilic inflammation and rule out other causes. Treatment with corticosteroids is often successful; however, relapse can occur after dose tapering.22

Pulmonary Edema

Noncardiogenic and cardiogenic edema are common causes of pulmonary parenchymal changes in dogs.

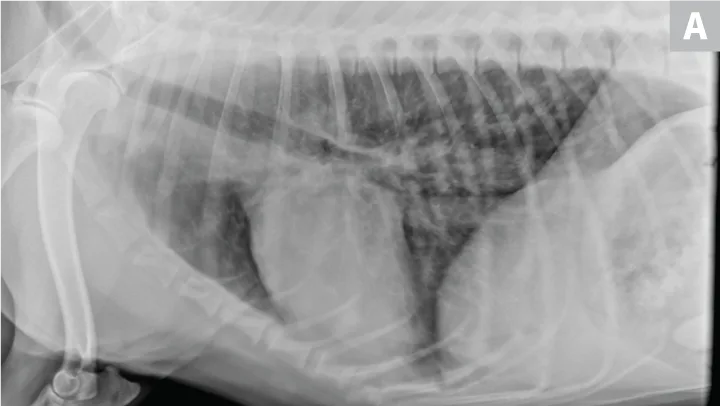

Cardiogenic edema is caused by increased hydrostatic pressure and is readily diagnosed by thoracic radiographic documentation of left-sided cardiomegaly, pulmonary venous congestion, and a patchy interstitial or alveolar pattern (frequently perihilar). Echocardiographic evaluation may support diagnosis.23 Natriuretic peptides may provide additional insight in differentiation between congestive heart failure and other causes of respiratory distress (Figure 4). Plasma B-type natriuretic peptide has been shown to have discriminatory value in dogs; however, some degree of overlap exists between groups.24

Figure 4A Congestive heart failure. Note the left-sided cardiomegaly, pulmonary venous congestion, and interstitial pulmonary pattern. Edema is not exclusively perihilar.

Noncardiogenic edema is a low-pressure edema characterized by increased blood vessel permeability. Seizures, electrocution, strangulation or upper airway obstruction, local pulmonary disease, and systemic inflammatory response syndrome (ie, acute respiratory distress syndrome) are the most commonly reported causes.25,26

Thorough clinical history and physical examination are necessary to identify potential underlying causes. Careful auscultation of the upper airways is important. Radiographs often reveal bilateral, caudodorsal interstitial, and/or alveolar disease. Radiographic progression can occur for as long as 48 hours.27

Lungworms

Lungworms may cause bronchitis and pneumonia. Chronic coughing is the most common clinical sign. Acute-onset exercise intolerance and/or respiratory distress may also be seen.

Radiographic evaluation can vary from a diffuse bronchointerstitial pattern to patchy interstitial or alveolar infiltrates (Figure 5).28 Bullae may occasionally be appreciated in association with some infections (eg, Paragonimus kellicotti).29-31

Crenosoma vulpis (ie, lungworm). Note the patchy, unstructured interstitial densities. Larvae were recovered on bronchoscopy.

Peripheral eosinophilia is not always present with infection. Eosinophilic inflammation on airway cytology supports diagnosis. Identification of larvae or oocysts via fecal testing (eg, Baermann technique, fecal centrifugation) or airway sampling confirms diagnosis.32 False-negative results can occur; any patient with eosinophilic bronchitis should be treated empirically. An extended course of fenbendazole (ie, 2 weeks) is generally recommended to treat most pulmonary worms.

Lung Lobe Torsion

Spontaneous lung lobe torsion occurs in dogs (most commonly pugs and Afghan hounds33), can occur in any lung lobe, and may be secondary to pleural effusion or thoracic surgery. The right middle lung lobe is overrepresented in deep-chested dogs; the left cranial lung lobe is overrepresented in pugs.33,34

Nonspecific illness and respiratory signs may be appreciated. Leukocytosis, left shift, and pyrexia may be present.34 Radiographs often reveal an alveolar pattern, trapped gas (vesiculated), and/or pleural effusion. Bronchial malpositioning is uncommon (Figure 6).35 Confirmation via ultrasonography, bronchoscopy, and/or CT is recommended.36,37 Pleural fluid varies widely in gross and cytologic appearance. Although nonspecific, the presence of pleural fluid, alveolar disease, and acute respiratory signs is suggestive. Immediate lung lobectomy is warranted.

FIGURE 6 Lung lobe torsion. Note classic vesicular pattern associated with gas trapping and pleural effusion. Bronchial attenuation or displacement is subtle and often absent.

Pulmonary Neoplasia

Radiographs usually reveal structured interstitial densities within pulmonary parenchyma.38 These lesions may represent primary or metastatic lesions. Clinical signs are typically absent, although coughing is most common. Acute respiratory signs may occur secondary to generation of pleural effusion or bleeding from a lesion (ie, hemangiosarcoma metastasis). Depending on the extent of disease, anorexia, lethargy, and weight loss may be appreciated.39

Pulmonary neoplasia may, on occasion, have a more diffuse nature. This is common with pulmonary lymphoma40 and is sometimes seen with carcinoma (author experience). Pulmonary lymphoma can have a rapid clinical course and mimic acute disorders. A diffuse, unstructured interstitial pattern is typically appreciated. Additionally, bronchointerstitial, alveolar, and nodular patterns may be observed (Figure 7).40

(A) Pulmonary lymphoma with a diffuse, patchy bronchointerstitial pattern confirmed on bronchoalveolar lavage and peripheral lymph node aspiration. (B) Pulmonary carcinoma with a diffuse, severe bronchointerstitial pattern confirmed on bronchoalveolar lavage and postmortem examination. Note: Pulmonary and hilar lymphadenopathy are not always present.

Diagnosis of pulmonary lymphoma requires airway cytology, pulmonary fine-needle aspiration, and/or confirmation on nonpulmonary samples.41

Carcinoma frequently causes anorexia and weight loss and should be considered in older patients with refractory pneumonia.42

Pulmonary Embolism

Pulmonary embolism (PE) should be suspected in dogs with acute respiratory signs, hypoxemia, and minimal radiographic changes. More common disorders should be ruled out. Radiographic findings vary from normal to patchy/wedge-shaped alveolar/interstitial infiltrates. Pulmonary oligemia may be appreciated in some patients (Figure 8).

Pulmonary embolism confirmed on necropsy. Note the right caudal lung field oligemia, which signifies vascular occlusion.

Diagnostics should focus on documenting a predisposing hypercoagulable state and attempting to confirm thrombosis. d-dimers, contrast angiography, echocardiography, nuclear medicine, and thoracic CT may indicate PE.43-45 Microvascular thrombosis may only be documented on necropsy. However, no test can reliably rule out PE; therefore, treatment must be considered for patients in which the condition is suspected. Optimal management has not been described; however, anticoagulant therapy is standard in human patients. Thrombolytic therapy is standard in humans with massive pulmonary thromboembolism (hemodynamically unstable). Recently, subpopulations of submassive pulmonary thromboembolism (hemodynamically stable) have benefitted from thrombolytic therapy.46 Optimal thrombolytic protocols have not been designed for dogs or cats.

Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) may be a primary vascular disorder or secondary to cardiac disease, pulmonary disease, or pulmonary embolism. The most commonly cited causes of PAH in dogs include chronic acquired valvular disease, pulmonary disease, pulmonary overcirculation, and heartworm disease.47-52 Primary pulmonary hypertension has been described in dogs in association with a pulmonary arteriopathy53 and a primary pulmonary veno-occlusive condition.54 Patients may be subclinical or may show signs of hypoxia (eg, weakness, fatigue, shortness of breath, exercise intolerance, collapse, syncope, right-sided congestive heart failure [rare]). Coughing is common and is often associated with secondary causes of PAH.52 Radiographic features and physical examination results generally reflect the underlying disease process; rarely, pulmonary edema may be observed.55 Investigation may be warranted in at-risk patients (ie, patients with diffuse crackles, West Highland terriers with pulmonary fibrosis).

Documentation of PAH can be performed indirectly with echocardiography.56,57 Direct pulmonary arterial measurement is rarely performed. PAH often contributes to signs with any chronic cardiopulmonary disease; thus, screening is recommended. Phosphodiesterase type V inhibitors (eg, sildenafil,49,50,58 tadalafil59), pimobendan,60 and imatinib61 may be considered, depending on cause.

Interstitial Lung Diseases

Interstitial lung diseases are an uncommon cause of respiratory disease in general. The most common interstitial lung disease is idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, which occurs most commonly in West Highland terriers.62 Because of the interstitial location of interstitial lung diseases, histopathology is required for definitive diagnosis.63 Common signs include exercise intolerance, labored breathing, syncope, and weakness.64 Coughing is typically not present. Examination may reveal crackles, fatigue, cyanosis, and a restrictive breathing pattern.

Radiographs may reveal a diffuse, unstructured interstitial pattern (Figure 9). Subtle changes in interstitial opacity may go unnoticed despite severe histologic disease.62

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis with a diffuse bronchointerstitial pattern. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis was confirmed on lung biopsy.

Thoracic CT may provide strong support with a characteristic diffuse “ground glass” appearance.65 This remains nonspecific, however, and may be caused by other conditions. Additional supportive diagnostics may include bronchoalveolar lavage biomarkers (eg, endothelin-1)66 as well as echocardiography to document secondary pulmonary hypertension.

Additional Disorders

Other pulmonary conditions in dogs include atypical infections (eg, Mycobacterium spp, protozoal),67,68 traumatic injuries (eg, pulmonary contusions, near-drowning), and inhaled irritants (eg, pneumonitis, smoke). It is important to note that the lungs may represent a manifestation of systemic disease (eg, leptospirosis, acute respiratory distress syndrome, anaphylaxis, transfusion-related acute lung injury).