Clinical Suite: Fracture Management

Erin Wood, LVMT, University of Tennessee

Zenithson Ng, DVM, MS, DABVP (Canine & Feline), University of Tennessee

Karen M. Tobias, DVM, MS, DACVS, University of Tennessee

Nan Lillard, MA, University of Tennessee

Overview

Erin Wood, LVMT, University of TennesseeZenithson Y. Ng, DVM, MS, University of TennesseeKaren M. Tobias, DVM, MS, DACVS, University of Tennessee

A fracture is traumatic for both the pet and pet owner and requires compassionate care and expertise from the veterinary team. Clients should immediately seek attention if they suspect their pet has a fracture. Fracture patients should be completely evaluated for more extensive trauma, regardless of the fracture origin. Stabilization of the fracture site and appropriate pain management are the mainstays of treatment. The prognosis for return to function depends on the type of fracture, method of stabilization, and postoperative care. The team’s ability to provide exceptional care and communicate effectively with clients will determine a successful outcome.

Related ArticleFracture Management: Training a Supportive & Effective Team

FRACTURE LOCATIONS

The most common fractures reported in trauma cases affect:

Forelimbs1

Scapula

Elbow (luxation)

Radius

Hindlimbs1

Pelvis

Femur

Hip (luxation)

Distal limb

Axial skeleton1,2

Ribs

Spine

Sacral (luxation or fracture)

BLUNT TRAUMA

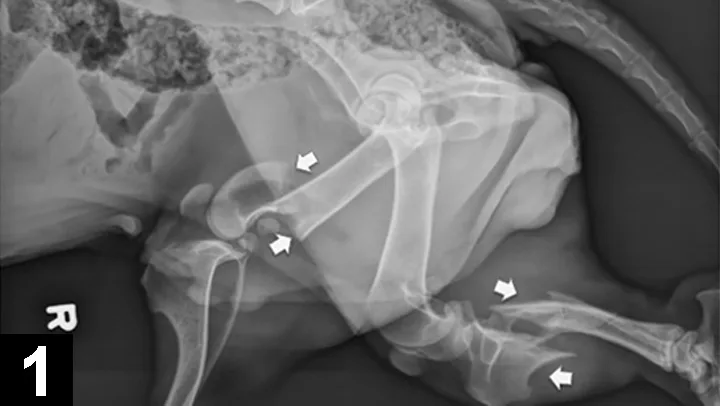

Blunt (eg, vehicular) trauma patients often experience multiple injuries (Figure 1). Patients are often only treated for the obvious fracture, causing additional traumatized tissues or disease processes to go unnoticed and untreated. Signs may not show for hours or days, which could alter the outcome of the treatment plan.3 Common additional injuries (affecting 25%–50% of blunt trauma patients) include:

Soft tissue trauma (eg, abrasions, lacerations, degloving injuries)

Thoracic trauma (eg, pulmonary contusions, hernias, fractures); hemorrhage may be present.

Abdominal trauma (eg, hemoabdomen, uroabdomen, hernias)

Head trauma (eg, skull fractures)2,3; signs may include epistaxis and neurologic abnormalities.

Lateral radiograph of an adult basset hound presented for inability to walk on its hind legs, without evidence of superficial abrasions or bruises. The arrows mark a distal femoral fracture and a proximal tibial fracture.

FRACTURE REPAIR

The goal of fracture repair is to stabilize the fractured bone, enabling rapid healing and return to full function. Surgical repair should be performed as early as possible in stable patients.

Open fractures are best treated with wound and bone debridement within 8 hours, but repair may be delayed 24–48 hours.

Closed fractures are best treated within 1–4 days.4

For complex fractures (eg, spinal, articular, distal radial and ulnar in small breed dogs), consider consultation with a boarded veterinary surgeon or referral to a specialty practice.

OTHER OPTIONS

Alternatives to primary bone repair include external coaptation and amputation.

A spica splint can be used to immobilize the elbow joint for a proximal fracture of the radius and ulna.

External coaptation may be successful in fractures below the elbow or stifle, where the joints above and below the fracture can be fully immobilized.3

Ensure the chosen splint or bandage will withstand bending, rotation, and distractive and compressive forces, and will adequately immobilize the site without causing complications (Figure 2).

Before choosing external coaptation, discuss the implications with the client:

Financial commitment (costs of bandage changes, sedation, analgesia, materials, multiple radiographs)

Time commitment (weekly rechecks)

Potential for bandage-associated wounds with long-term use

Risk of failure: As many as 80% of splinted distal radial or ulnar fractures result in nonunion or delayed union because of variations in blood supply to the distal bone and difficulty immobilizing the elbow, thereby impeding healing of the fracture line.5,6

Need for appropriate compliance (eg, proper confinement).

Clients may choose amputation for financial reasons.

Contraindications for amputation include:

A fracture that is amenable to external coaptation or cage rest

Severe orthopedic or neurologic disease affecting other limbs

Extreme obesity

Previous limb amputation

Evidence of other existing orthopedic issues (eg, hip or elbow dysplasia, osteosarcoma).

Primer

Erin Wood, LVMT, University of TennesseeZenithson Y. Ng, DVM, MS, University of TennesseeKaren M. Tobias, DVM, MS, DACVS, University of Tennessee

Patients presenting with fractures should receive a complete physical examination, and radiographs should be taken to determine the extent of damage. When the underlying cause is traumatic or suspected to be neoplastic, thoracic and abdominal radiographs and full blood work are recommended. Blood work is also required for fractures requiring surgical stabilization. A CBC, chemistry panel, urinalysis, and/or coagulation profile may be required to safely anesthetize the patient. Taking these steps allows veterinary team members and clients to make the best treatment decisions.

PATIENT TRANSPORTATION

The client should be advised on how to safely transport his or her pet to the practice:

Small pets should be contained in carriers.

The patient can be lifted using a blanket stretcher; a sling can assist in ambulation.

The client may place a towel over the patient’s head to minimize the risk of biting.

Open wounds should be covered with clean towels to minimize contamination.

The client should allow practice team members to transport the patient into the practice, which can be done safely and quickly with a wheeled cart (Figure 3).

A wheeled cart can help safely transport fracture patients. Also, a muzzle allows for safe assessment of the patient.

PRESENTATION

Ask the following questions on presentation:

When and how did the fracture(s) occur?

Are there any concurrent disease processes?

Is the patient on any medications?

EXAMINATION

Assess the patient’s airway, breathing, and circulation, and examine for evidence of hemorrhage.

Check vitals and complete initial diagnostics (TPR, weight, blood pressure, PCV/TS/BG, ECG, SpO2; see Acronyms).

Complete physical, orthopedic, and neurologic examinations.

Obtain radiographs of the affected area.

Consider obtaining radiographs of the abdomen, thorax, and spine. Abdominal and thoracic ultrasound may be necessary to detect hemorrhage (Figure 4).

If open wounds and/or fractures are present, obtain a deep tissue sample for culture, then administer broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Evaluate the CBC, chemistry, and coagulation panel (if available) to determine the patient's overall health status.

Abdominal and thoracic ultrasound are sometimes necessary to detect hemorrhage or other serious pathology following trauma.

TREATMENT

Stabilize the patient as needed (eg, place IV catheter, administer oxygen and fluids).

Administer pain medications and sedatives as needed.

Consider using opioids in conjunction with NSAIDS for multimodal pain management. NSAIDS should be avoided in patients who are hypotensive, hypovolemic, or in shock, or whose blood work shows evidence of renal or hepatic disease. NSAIDS should also be avoided in patients who are already on drugs that could cause adverse reactions.

Sedation will facilitate further diagnostics/imaging.

Once analgesics are given, apply sterile lubricant and clip the wounds. Consider collecting samples for culture before cleaning. Flush the wounds with a copious amount of 0.9% buffered sterile saline, which will decrease bacteria by 90%; clean with an antimicrobial. Cover with nonadherent, sterile dressing.6

Discuss assessment, treatment options (eg, external or internal fixation, cage rest, external coaptation, amputation, referral surgery), prognosis, and finances with the client.

If repair is delayed, temporarily immobilize lower limb fractures with a bandage or splint to improve patient comfort and decrease further soft tissue trauma.

TEAM SAFETY

Muzzle patients to allow for safe assessment of wounds.

Wear examination gloves to minimize contamination of open wounds and to protect team members.

BG = Blood GlucoseECG = ElectocardiogramPCV = Packed Cell VolumeSpO2 = Oxygen SaturationTS = Total SolidsTPR = Temperature, Pulse, Respiration

Communication

Nan Lillard, MA, University of TennesseeZenithson Y. Ng, DVM, MS, University of Tennessee

Fractures are likely unforeseen and their financial considerations unanticipated. Team members should be prepared to provide support to the client and veterinary care team when these cases present by remaining calm, compassionate, and responsive.

Related ArticlesFracture Management: Training a Supportive & Effective TeamFrequently Asked Questions: Caring for Your Pet’s Fracture

Understanding a client whose pet has a fracture

Clients may experience many feelings in response to their pet’s traumatic injury, including guilt, anger, fear, sadness, and shock.

It may be difficult to communicate with emotional or angry clients. They likely are responding with their emotional brain—not their logical brain. Do not take negative attitudes or conversations personally.

Supporting the client

Address the client’s most immediate need first: to get medical attention for his or her pet.

Thank the client for seeking the best possible care for the pet.

Take care of any remaining client needs (eg, tissues, food, water, clean clothes, information, an area that is quiet and private).

After the patient is taken to the treatment area, the receptionist should assure the client that the veterinary care team is attending to the pet and will provide an update after the initial assessment.

Address the client and patient by name and correct gender.

Communicating with the client

Be supportive and assuring (eg, Our team is attending to Annie’s needs. We are committed to providing her with the very best possible care).

Follow the client’s lead. If he or she wants to talk about the pet, listen actively and respond compassionately. Acknowledge the client’s good care and loving relationship with the pet as presented in the stories and information shared with you.

Acknowledge the client’s feelings (eg, It sounds like you’re very concerned about Annie). This will allow the client to confirm his or her feelings or correct your perception, and move from an emotional reaction toward logical responses.

If you must step away from the client to attend to other responsibilities, explain the reason and promise to check back soon.

Avoid making statements that allude to a good prognosis (eg, Don’t worry. Everything will be okay).

Do not tell the client not to cry. Offer tissues if needed.

Workflow

Nan Lillard, MA, University of TennesseeErin Wood, LVMT, University of Tennessee Zenithson Y. Ng, DVM, MS, University of Tennessee

The workflow below can help your team successfully treat fracture patients and improve client communication.

1. Receptionist

Greet and provide support to the client

Alert the veterinary care team immediately upon the patient’s arrival

Provide or create a medical record

Communicate information from the client to the team

2. Technician/Assistant

Receive the patient

Triage the patient and check his or her vitals

Stabilize the patient (eg, place the IV catheter, administer oxygen and fluids)

Clip and clean the wounds; collect samples for culture, if needed

3. Veterinarian

Perform physical, orthopedic, and neurologic examinations

Administer medications, sedatives, and antibiotics

Assess the clinical presentation and diagnostics

Discuss assessment, treatment options, prognosis, and finances with the client

Administer treatment

4. Technician/Assistant

Provide supporting educational information to the client about the patient’s condition and recommended treatments

5. Receptionist

Discuss payment options

Collect deposits and payments for services

Schedule follow-up appointments

Provide documentation and forms for referral, if necessary

Roles

Nan Lillard, MA, University of Tennessee Erin Wood, LVMT, University of TennesseeZenithson Y. Ng, DVM, MS, University of Tennessee

From facilitating communication to triaging and stabilizing the patient, each team member has a specific role in managing fracture cases. Use the chart below to clarify each team member’s responsibilities.

Training

Nan Lillard, MA, University of TennesseeZenithson Y. Ng, DVM, MS, University of Tennessee

Developing skills to support clients and patients during traumatic events before they are needed is key to a practice’s effectiveness and, ultimately, success in these situations. Training should be periodically reviewed with the entire team.

Basic Training

This is an opportunity for the practice manager to collaborate with the veterinarian to provide training and clarify roles to the entire team.

Effective training includes information on how to communicate during difficult times and about difficult subjects, and outlines each team member’s role and responsibilities. A veterinarian should give a presentation on fractures, including types of fractures, treatment options, and typical follow-up care required. To summarize and put training into action, role-play to practice specific scenarios.

Related ArticlesEmergency Fracture Management at a GlanceFracture Management: Supportive Client Interaction

Suggested content for the practice manager’s presentation:

Communicating with an emotional client when his or her pet suffers a traumatic injury or during other difficult situations

Communicating about financial considerations during an emergency situation

Clarifying each team member’s role when an urgent/emergent case presents

Educating clients about at-home management.

Suggested content for the veterinarian’s presentation:

Safely handling a painful fracture patient

Preventing further injury to the patient

Preventing the patient from biting team members or the client

Providing pain medication

Stabilizing a critical patient

Types of fractures

Treating fractures

Home care and prognosis for fracture patients.

Suggestions for role-play:Develop scenarios in which a client in crisis brings his or her pet to the practice with a traumatic fracture.

Focus on the team’s ability to stay calm in difficult situations and meet the patient’s needs, followed closely by the client’s needs.

Take the lead from the client during conversation.

Avoid alluding to a good prognosis to comfort the client (eg, It will be okay. Don’t worry).

Handout

Erin Wood, LVMT, University of TennesseeZenithson Y. Ng, DVM, MS, University of TennesseeKaren M. Tobias, DVM, MS, DACVS, University of Tennessee

Q: What is the prognosis for my pet to return to normal function after surgery, splinting, or amputation?

A: Fracture healing is dependent on the type of fracture, type of repair, and the patient’s age, size, and activity level after repair. Early signs of bone healing are radiographically present after 4–6 weeks. Patients requiring amputation typically adapt quickly to the loss of the limb, as long as they do not have other problems that inhibit mobility.1

Many patients adapt quickly following a limb amputation.

Q: Wouldn’t it be cheaper and easier to splint the leg?

A: Splinting or casting is not always the cheapest or easiest method of repair. It involves multiple rechecks and bandage changes, additional radiographs, and potential for delayed healing. Splinted fractures will not heal if they are not stable. In addition, placing a splint across a joint for several months may lead to problems in the leg.

Q: What nursing care is required?

A: Studies show that patients suffering from severe blunt trauma have more successful outcomes when treated in an intensive care unit.2 However, no matter the type of repair, at-home care is critical for fracture healing.

The patient must be confined for several weeks to speed bone healing, prevent bandage slipping, and reduce the risk of implant failure. This usually means crate rest—no running, jumping, or any exercise off-leash—with leash walks (limited to 5 minutes) 3–4 times per day for bathroom breaks. The patient may need assistance standing and walking using a sling or similar device.

A fracture patient can be helped to stand and walk with a sling.

The bandage or splint should be kept clean and dry. Bandages can be covered with a plastic bag when the patient is taken outside. Wet or dirty bandages should be changed as soon as possible by a veterinary professional to help prevent sores or infection. E-collars (ie, protective cones that prevent pets from biting or licking their wounds) may be necessary to prevent patients from chewing the bandage or surgical site.

Contact your veterinarian immediately if the bandage slips, your pet’s toes or legs swell, or your pet chews the bandage. Under no circumstance should you modify a bandage or splint without direct guidance from a veterinary professional.

Physical rehabilitation can facilitate a quicker return to function. Check with your veterinarian for available programs or an at-home regimen.

Q: How do I recognize a problem?

A: Watch for these signs:

Excessive redness, swelling, or discharge from the incision or wound

Excessive swelling of the toes or extremities above or below the bandage

Sudden increase in pain or lameness

Loss of appetite

Lethargy

Fever

Malodor