Clinical Suite: Canine Lyme Disease

Steven A. Levy, VMD, Veterinary Clinical & Consulting Services, LLC, Durham, Connecticut

Mary Ann Vande Linde, DVM, Vande Linde & Associates, Brunswick, Georgia

Overview

Steven A. Levy, VMD, Veterinary Clinical & Consulting Services, LLC, Durham, Connecticut

Canine Lyme disease is most commonly diagnosed as a limb or joint abnormality (ie, Lyme arthritis), a less common but often fatal kidney failure syndrome, a rare cardiac form, or an also rare neurologic abnormality. The disease is caused by Borrelia burgdorferi and vectored by Ixodes scapularis in the eastern half of the United States and I pacificus on the west coast.

Canine Lyme arthritis patients present with lameness, fever, swollen joints (often carpus or tarsus), a reluctance to move, and inappetence.1

Canine Lyme disease is most commonly diagnosed as a limb or joint abnormality.

Lyme nephritis is a severe protein-losing nephropathy2 characterized by hypoalbuminemia, proteinuria, and elevated blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, and phosphorus. Patients have a history or risk of tick exposure and a positive point-of-care test. Aggressive therapy is directed toward resolving azotemia, renal hypertension, and other abnormalities but is usually unsuccessful, resulting in death or euthanasia within days of presentation.

Lyme carditis is rare, with only one peer-reviewed reported case.3 Although humans with Lyme disease often exhibit neurologic abnormalities, reports of facial paralysis and seizures in dogs have not been convincingly linked to B burgdorferi infection.4

Joints of dogs presenting with lameness, fever, anorexia, lymphadenomegaly, history of tick exposure, and positive Lyme serology; both dogs responded rapidly to antibiotic therapy.

Diagnosis & Treatment

Diagnosis of any form of canine Lyme disease is a clinical conclusion based on appropriate signs, epidemiologic risk, rule-out of an alternate diagnosis, demonstration of infection with the etiologic organism, and, in the case of Lyme arthritis, a response to appropriate therapy.1 Diagnosis is typically made by determining that the patient is either from or has traveled to an active vector region, and by ruling out other causes(eg, trauma, immune-mediated arthropathy, degenerative joint disease).

Additionally, 2 point-of-care tests are available for determining B burgdorferi infection status which, when linked with the above diagnostic criteria and rapid improvement after initiation of appropriate antibiotic therapy, leads to a diagnosis of Lyme arthritis. Note that infected dogs may often have a positive test but are asymptomatic at the time of testing.5

Treatment & Prevention

Steven A. Levy, VMD, Veterinary Clinical & Consulting Services, LLC, Durham, Connecticut

Many dogs that present for annual preventive testing (eg, for heartworm, Lyme, other tick-borne diseases) are Lyme-positive without apparent signs. Infected dogs are at a 5%5 to 10% risk of developing signs of Lyme disease and are unlikely to survive if they develop renal disease.

Vaccinating Lyme-positive dogs has been demonstrated to be safe.6 Treating asymptomatic positive dogs has been demonstrated to reduce antibody titers7; however, there is evidence that Lyme infections are persistent even after antibiotic therapy.8

When a patient is diagnosed with Lyme arthritis, antibiotic therapy is initiated with injectable penicillin, followed by 14 days of oral amoxicillin. For dogs presumed to have Lyme nephritis, discuss with the client further testing (eg, blood chemistry, complete blood count, urinalysis), in-patient care, intensive therapy, and a guarded prognosis.

Prevention

Vaccination of at-risk dogs before exposure to infected vector ticks is a part of disease prevention. Two types of vaccines with demonstrated safety and efficacy are available: a recombinant vaccine with a single protein from the causative organism, which immunogenicity studies have suggested may provide maximum protection with twice-yearly immunizations, and another vaccine that contains multiple proteins of B burgdorferi, which immunogenicity studies have suggested will maintain effective immunity with annual boosters.9

Preventing Transmission

Successful transmission of the Lyme agent from a tick to a dog requires a minimum of 24 hours of tick attachment and feeding and is most efficient at 48 to 52 hours post-attachment.

A rapidly acting acaricide will prevent tick feeding by either killing ticks or rendering them moribund before they attach.

Spot-on products and some collars can achieve clinical repellence, essentially shielding dogs from ticks by rapid killing and attachment prevention.

New oral products are highly effective at killing ticks but often allow some period of feeding, thus providing an opportunity for transmission of B burgdorferi or other tick-borne organisms.

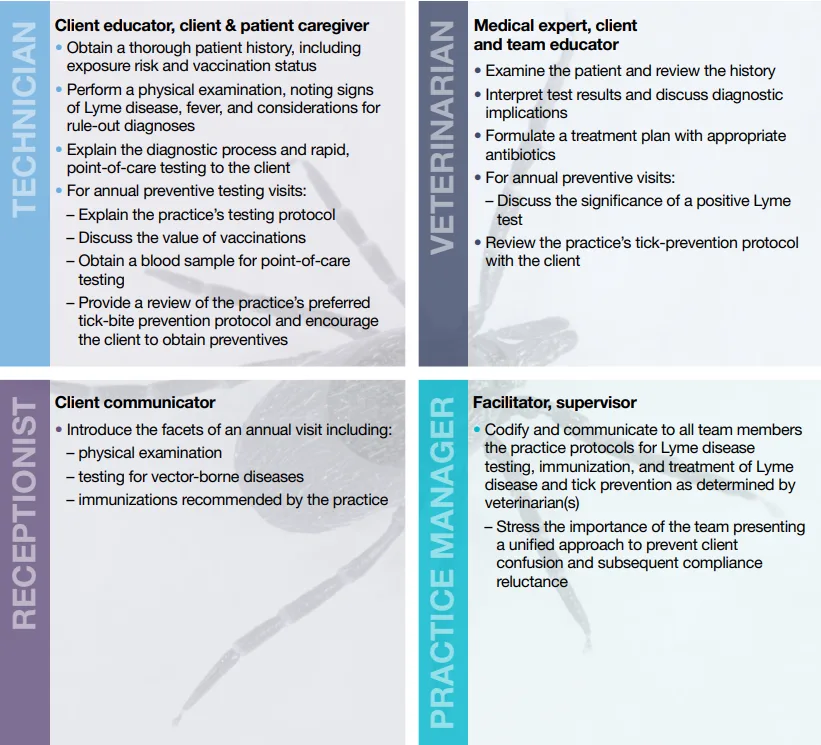

Team Roles

Steven A. Levy, VMD Veterinary Clinical & Consulting Services, LLC, Durham, Connecticut

The following guide outlines each team members role and responsibilities, from client education to diagnosis and treatment.

Team Training

Mary Ann Vande Linde, DVM, Vande Linde & Associates, Brunswick, Georgia

Many products now are available to prevent, control, and treat parasites internally and externally, and the veterinary team is the clients most valuable resource when choosing a product. Too many product options and too little team education can overwhelm clients and decrease compliance.

Basic team training should organize and focus the team so all members are on the same page. The practice manager, veterinarian, veterinary technician, and other team members should define their roles and prepare messages, handouts, websites, and processes to recognize patients at risk. A team approach is the best way to deliver accurate and timely information consistently to clients.

Training must be easy to understand and explain. Offer teaching aids nonmedical team members can refer to when talking with clients; these are referred to as just-in-time learning and support and can be handouts, websites, Youtube videos, or pamphlets created by the practice or a vendor (see Useful Training Aids). The training team must select, review, and utilize the selected resources during training presentations.

Team training for Lyme disease should cover the following:

Disease name

Disease in dogs vs humans

Risk in geographic and travel areas

Cause of the disease and the organism of transmission

Significance of patient travel history

Clinical signs

Diagnostic testing

Treatment

Immunization

Follow-up and management.

Role-play is vital to the success of any program. Team members should take turns acting out each role (eg, veterinarian, veterinary technician, receptionist, client). Use scripts and simplified messages to make role-play engaging and less threatening.

Use these tips to train the veterinary team to in turn train clients:

Keep it simple

Keep it consistent

Create just-in-time options

Handouts

Key apps & websites

Pamphlets & videos

Create instruments to test learning

Role play

Use Survey Monkey

Watch team members in action as they educate a client

Measure the training results and set goals

Review goals daily or weekly at team meetings

Have team members talk to community organizations (eg, schools, service clubs).

Useful Training Aids

Youtube: Search for high quality, reliable tick removal videos

Communication Keys

Mary Ann Vande Linde, DVM, Vande Linde & Associates, Brunswick, Georgia

To decrease confusion and keep clients active in their pets health, the veterinary team must communicate a consistent message. A recent study by the Companion Animal Parasite Council (CAPC) showed that 74% of pet owners want their veterinarian to provide more information about parasite testing, and 90% want to be notified if there is a high incidence of parasites in their county; also, 89% are likely to make an appointment to get their pet tested based on this risk.1

The Rule of 3 provides clear, concise, comprehensive talking points:

The risk of the disease in the area

The patients risk for an uncomfortable disease

Easy and cost-effective solutions.

The following is an example for a Brunswick, Georgia, patient:

The incidence of Lyme disease is moderate, according to the CAPC app. In Georgia, one out of every 203 dogs is positive for the disease.

The carrier tick (ie, Ixodes scapularis) is seasonally active in the spring and feeds intensely in the fall.

The patient can be tested during the examination with an in-house blood test. Then, with the clients input, the best prevention steps can be determined.

Clients need to connect with the recommendation by seeing or experiencing how their pet could be at risk. Questions to review the risk include:

How and where does your pet exercise?

How does your pet interact with other animals?

How is your home protected from parasites or unwanted bugs?

What concerns do you have about parasites inside your home?

Describe your backyard.

Educate clients with simple steps on tick exposure and prevention at home and while traveling. Also, consider showing a computer presentation or video or providing handouts to address all client concerns.

Companion Animal Parasite Council study10

74% Pet owners who want more details about parasite testing

90% Pet owners who want information about local parasite incidence

89% Pet owners likely to get their pet tested based on risk.

Canine Lyme Disease: Common Client Misconceptions

Steven A. Levy, VMD, Veterinary Clinical & Consulting Services, LLC, Durham, Connecticut

The ticks that transmit Lyme disease are tiny:

Adult Ixodes scapularis ticks are the stage when the parasites preferentially feed on dogs and are as large as the common dog tick (about the size of a small raisin when fully engorged).

Tick exposure risk is a spring event:

I scapularis adults have a biphasic seasonal activity with a spring peak and a period of intense feeding activity in the fall. I pacificus is most active in the cooler, wet seasons.

A positive rapid test is diagnostic for disease:

A positive test is evidence of infection. Infection with B burgdorferi is likely persistent, even with appropriate antibiotic therapy, but a diagnosis of Lyme disease requires presence of appropriate clinical signs.

A positive dog may not be safely vaccinated and there is no value to immunizing such a dog:

Vaccination of vast numbers of infected dogs in the 25 years since introduction of the first canine Lyme vaccine and many peer-reviewed papers indicate that it is safe.

A study published in JAVMA in 1993 demonstrated that immunizing Lyme-positive dogs reduced the subsequent incidence of disease by approximately 50%.

Unpublished research indicates that immunization and antibiotic treatment of asymptomatic Lyme-positive dogs can reduce the incidence of clinical episodes to virtually none.

Over-the-counter (OTC) tick-control products are cheaper than veterinarian-dispensed products, just as safe, and just as good:

Some OTC products may be effective, but without the involvement of a veterinary healthcare professional the client may:

Choose an inferior product and lose faith in all acaricides

Use a product in an inappropriate fashion, causing adverse events

Use a product on an inappropriate species, causing adverse events

Fail to understand the need for continued use of acaricides even after spring and summer in temperate areas.

It is advisable to wait until a puppy is mature to begin Lyme immunization:

Lyme vaccines are safe for puppies

The opportunity for tick exposure increases as puppies spend more time outside

Lyme vaccination before an infected tick bite is the best way to prevent all forms of canine Lyme disease.