Chronic Enteropathy in Cats

Heather Kvitko-White, DVM, DACVIM (SAIM), KW Veterinary Consulting, Kansas City, Missouri

Background & Pathophysiology

Chronic enteropathy refers to GI signs of >3 weeks’ duration.1-4 Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and small cell lymphoma are the most common causes of chronic enteropathy in cats in which infectious and non-GI causes have been excluded. These diseases also have clinical and histopathologic similarities that can complicate differentiation.2-4 Slow progression of IBD to low-grade lymphoma is suspected but has not been proven.3,5-7

In patients with IBD, the underlying cause of inflammation is multifactorial and incompletely understood; however, there is ongoing research on the role of the microbiome in local immune regulation, GI barrier function, and inflammation.8-14 Metabolites produced by gut microbes help maintain body functions (eg, metabolism, immunity, GI tract motility).8,9 Dysbiosis describes fluctuations in the number of various bacteria and their metabolites; changes in the relative proportions of 7 bacterial targets are characterized by decreased numbers of beneficial bacteria (eg, Bacterioides spp, Bifidobacterium spp, Faecalibacterium spp, Turicibacter spp, Clostridium hiranonis) and increased numbers of pathogenic bacteria (eg, Escherichia coli, Streptococcus spp) and can be measured via quantitative PCR in cats and dogs.1,10,11

History & Clinical Signs

IBD can occur in cats of any age, breed, or sex but is most frequently diagnosed in middle-aged and older cats.1,11-18 Clinical signs are variable; vomiting and weight loss are most common and typically coincide with changes in appetite.15-17 Diarrhea is possible and can be small, large, or mixed bowel. Borborygmi, flatulence, and ascites are less common in cats as compared with dogs.11-15

CAUSES OF GI TRACT INFLAMMATION IN CATS

Inflammatory

Feline triaditis (ie, IBD, pancreatitis, ± cholangitis)

Dysbiosis

Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency

GI eosinophilic sclerosing fibroplasia

Chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction (intestinal leiomyositis)

Infectious

Parasitic/protozoal

Ancylostoma spp

Cryptosporidium spp

Giardia spp

Toxocara spp

Toxoplasma gondii

Tritrichomonas foetus

Bacterial

Salmonella spp

Campylobacter spp

Clostridium spp

Helicobacter pylori

Fungal

Histoplasma capsulatum

Viral

FIV

FeLV

FIP

Neoplastic

Lymphoma (small, intermediate, ± large cell)

Adenocarcinoma

Mast cell neoplasia

Soft tissue/mesenchymal tumors

Miscellaneous

Intestinal foreign body

Intestinal obstruction

Acute gastroenteritis (eg, dietary indiscretion, intoxication)

Non-GI causes (eg, hyperthyroidism, moderate to severe renal or hepatic disease)

Diagnosis

Fecal ova and parasite testing should be performed to exclude infectious GI inflammation, and additional diagnostics should be performed to rule out non-GI causes of clinical signs (see Differential Causes of GI Tract Inflammation in Cats).

CBC results may be unremarkable or show a nonspecific nonregenerative anemia of chronic disease. Leukogram changes (eg, eosinophilia) are possible.2,15

Serum chemistry profile results may be unremarkable, have nonspecific changes, or be impacted by comorbidities. Protein-losing enteropathy caused by IBD is rare in cats; however, low blood cholesterol, albumin, and globulins suggest protein loss through GI causes (versus protein-losing nephropathy or hepatic insufficiency). Hypoproteinemia with melena, regenerative blood loss anemia, or iron-deficient nonregenerative anemia with or without increased BUN may suggest GI hemorrhage.

Serum cobalamin and folate levels reflect the absorptive ability of the ileum and proximal small bowel, respectively, and supplementation is indicated when they are deficient.2 Increased folate in a nonsupplemented cat may suggest dysbiosis; the feline dysbiosis index is also a diagnostic test for dysbiosis in cats with chronic enteropathy.1

Trypsin-like immunoreactivity should be evaluated to exclude exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, which is an underrecognized cause of vomiting and anorexia in cats with or without diarrhea.2,18 Many cats with IBD have concurrent pancreatitis with or without cholangitis (ie, triaditis) that may result in elevation of pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity levels.2,15

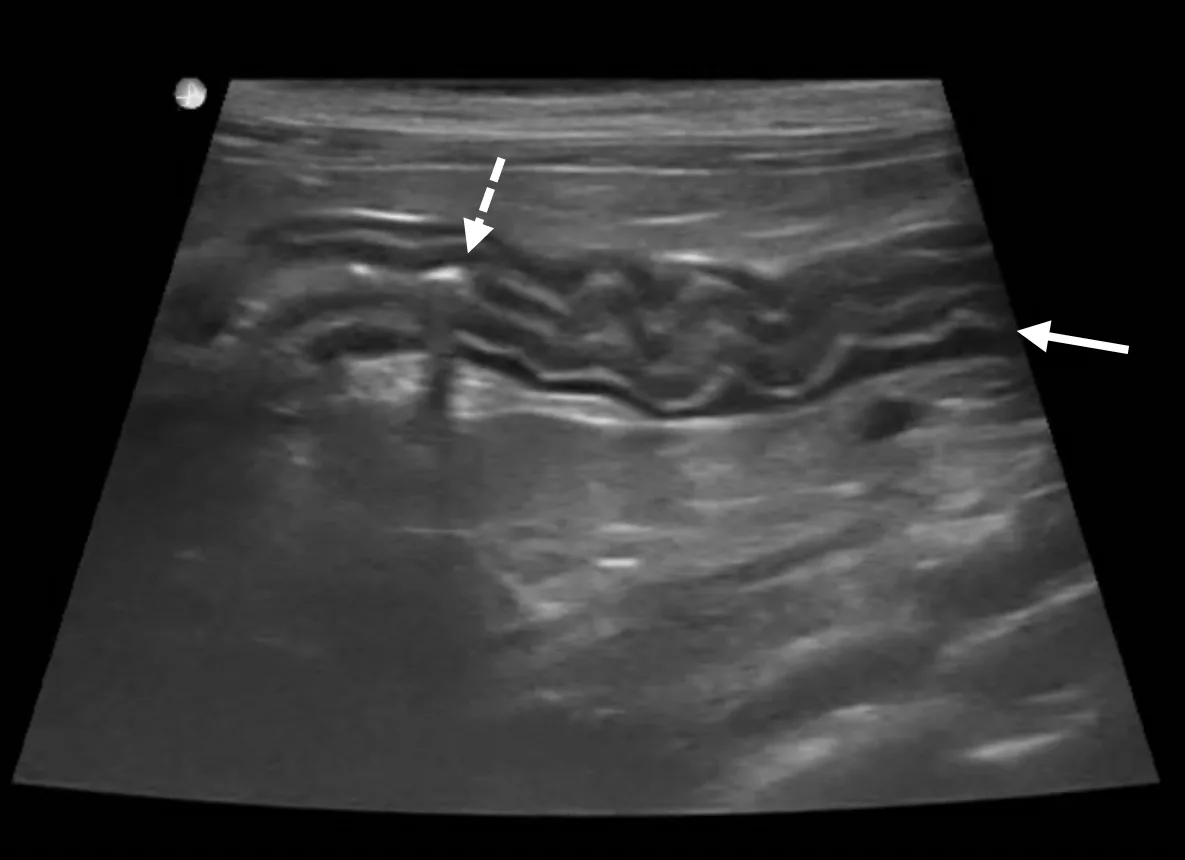

Radiography is nonspecific, and radiographs may appear normal. Ultrasonographic findings may include thickening of the general bowel wall or muscularis layer (Figure 1), mucosal changes, and mesenteric lymphadenopathy; however, ultrasonography is not sensitive or specific for IBD, and results may be normal.19,20

Ultrasound of the duodenum in a cat showing mild generalized muscularis layer thickening (arrow). The corrugated appearance and increased gas within the lumen (dashed arrow) support spastic hypermotility consistent with duodenitis, assuming an upper GI linear foreign body has been excluded.

Intestinal biopsies are required for definitive diagnosis, to rule out differentials (eg, neoplasia, certain infectious diseases), and to allow further classification of IBD based on cellular infiltration type (eg, eosinophilic, neutrophilic, lymphocytic/plasmacytic).21 Most feline IBD is caused by lymphocytic/plasmacytic and/or eosinophilic inflammation.21 Combining GI biopsies with immunohistochemistry and PCR for antigen receptor rearrangement (ie, PARR) improves the ability to differentiate IBD from lymphoma.3 Biopsies should be obtained through an endoscopic or full-thickness surgical approach (Figure 2). Applying and interpreting clonality testing presents additional clinical challenges; discussion is available in the literature.2-4

Classic belly button appearance of the ileocolic junction during routine colonoscopy. The shiny mucosal lining appears slightly hyperemic and edematous, although these findings can occur secondary to the endoscopy procedure. Partially open entry to the blind sac of the cecum is visible (arrow).

Treatment & Management

Many differential diagnoses for IBD require specific therapy; it is not feasible to treat empirically for all possibilities. Minimum treatment should include broad-spectrum deworming (fenbendazole, 50 mg/kg PO every 24 hours for 3-5 days). Otherwise, treatment should be tailored to the patient.

Many cats with IBD can be diet responsive, and a strict 2- to 4-week diet trial is often recommended as initial treatment. There are multiple dietary options (eg, highly digestible, novel protein, hydrolyzed protein, nonallergenic), and evidence supporting a specific diet in affected patients is lacking. Younger cats with predominantly large bowel signs may be an exception; a highly digestible, fiber-modified diet can be attempted first in these patients.

The author administers cobalamin when the patient has borderline low levels (<400 ng/L). Folate supplementation is rarely required or prioritized.

Antibiotic administration results in prolonged microbiota changes with potentially harmful effects in dogs and cats.22-24 Routine antibiotic trials and chronic use of low-dose or repeat courses of antibiotics are not recommended.

Prebiotics, probiotics, or synbiotics (ie, pre- and probiotic combinations) can be administered when diet alone does not control clinical signs; data to provide critical assessment of benefits are lacking.25 A positive response, if any, should be observed in 2 to 4 weeks.

Immunosuppression should only be considered in stable patients after thorough diagnostic evaluation, failed response to diet and probiotic trials, and pursual or pet owner decline of biopsies. Corticosteroids (eg, prednisolone, budesonide, dexamethasone) or chlorambucil may be administered as first-line options based on numerous factors, including comorbidities, cost, and owner ability to medicate the patient (Table). Sustained improvement with corticosteroids does not exclude a diagnosis of small cell lymphoma.

After stabilization of clinical signs and weight, the immunosuppressive dose should be tapered by ≈25% every 2 to 4 weeks until the lowest effective dose is determined. Some patients can be maintained on diet and/or probiotics alone following drug tapering, but continued treatment with one or more immunosuppressive medications may be required.

Fecal microbiota transplant has been performed in cats, but large-scale studies are lacking.26 Collaboration with a veterinary nutritionist should be considered.

IMMUNOSUPPRESSIVE MEDICATIONS FOR CHRONIC ENTEROPATHY IN CATS

Clinical Follow-Up & Monitoring

Objective markers of successful treatment include weight gain, improved BCS, and improved fecal consistency score; trends are more important than individual values. Monitoring can occur weekly, monthly, biannually, or perhaps annually, depending on initial disease severity.

Individual patient plans are needed because of comorbidities in middle-aged and older cats. Owner communication should be maintained, and the veterinary support team can help provide owner support through education and communication.

Prognosis

Chronic enteropathy in cats can be managed but not cured. Clinical signs may resolve, decrease, persist, increase, progress, or otherwise change over time. In one study of 62 cats with chronic enteropathy, median survival time in cats with IBD was 5.8 years compared with 1.3 years in cats with small cell lymphoma.27 Standard therapy should help maintain a good quality of life; further investigation or specialist referral is encouraged if quality of life is not maintained.