Chloramphenicol

Jennifer L. Buur, DVM, PhD, DACVCP, Western University of Health Sciences

Overview

Chloramphenicol is a broad-spectrum, bacteriostatic anti-microbial agent that acts through the inhibition of protein synthesis via the 70S ribosome and its 50S ribosomal subunit.

Due to high lipophilicity, it has good penetration into protected sites (eg, brain, aqueous humor, prostate).1

Although adverse effects limit use of chloramphenicol as a first-choice treatment, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius is often susceptible.2

Adverse Effects & Risk Factors

Common adverse effects in dogs include GI upset (eg, vomiting, diarrhea, anorexia, drooling, gagging), lethargy, restlessness, increased hepatocellular enzymes, and generalized trembling or shaking.2

Anemia and other bone marrow suppression can occur secondary to mitochondrial damage at high doses or extended durations.

Dogs can experience effects at doses of 225 mg/kg for 14 days or 50 mg/kg for 50 days.2,3

Cats are at higher risk than dogs because of deficiencies in effective glucuronidation enzymes that can lead to prolonged plasma, tissue, and, subsequently, mitochondrial concentrations.3

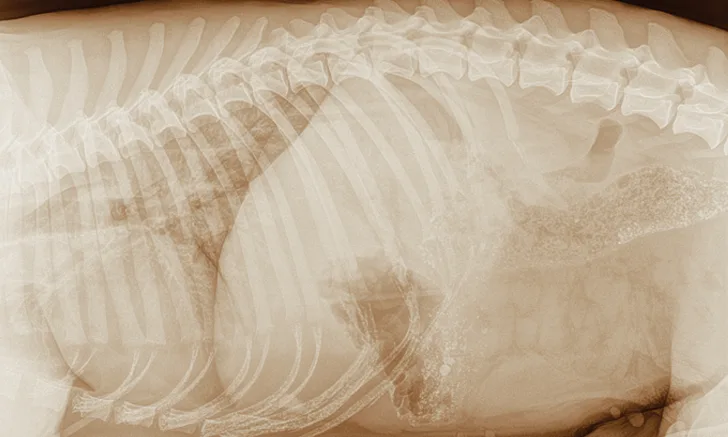

Peripheral neuropathy that manifests as pelvic limb weakness in larger dogs (>55 lb [25 kg]) has been reported.2

Signs resolved after the drug was discontinued.

Risk factors include a history of hepatic disease, neoplastic disease, polypharmacy, and exposure durations over 10 days.

Baseline and midtreatment CBC and serum chemistry profiles are recommended in patients with any of these factors.1,2,4

Humans are susceptible to developing anemia (dose-dependent and idiosyncratic aplastic forms) from inhibition of mitochondrial protein synthesis via the 70S ribosome.

Owners should be advised to handle the drug carefully and use appropriate protective equipment (eg, gloves, eye protection, facial shields) when needed.1,2

Drug Interactions

Efficacy is decreased when chloramphenicol is used with bactericidal drugs such as fluoroquinolones or other inhibitors of the 50S ribosomal subunit (eg, macrolides).1

Chloramphenicol specifically inhibits canine CYP2B11 and thus increases the half-life of methadone, barbiturates (eg, phenobarbital), digoxin, propofol, and primidone in dogs.5-7

Because of highly variable changes in drug pharmacokinetics, therapeutic drug monitoring of chronic medications (eg, phenobarbital) is recommended midway through and after treatment with chloramphenicol.

Patients should be monitored for such adverse effects as sedation, polyuria, and polydipsia during treatment.7

Chloramphenicol is metabolized by both phase I and phase II enzymes in the liver.

Hepatic dysfunction can increase plasma concentrations and half-life, which can lead to an increased risk for adverse effects.

Conversely, induction of P450 enzymes from concurrent administration of medications such as phenobarbital can decrease plasma concentrations and half-life, which can lead to a decrease in overall efficacy.1,5

Antimicrobial Stewardship

Selective pressure changes to normal flora can lead to resistance in fecal enterococci and a nosocomial source for multidrug-resistant bacteria with zoonotic potential.8

Cohabitation with dogs and cats has been associated with zoonotic transfer of multidrug-resistance (mdr) genes between enterococci.8

Resistance to chloramphenicol is associated with resistance to other antimicrobial agents.8

Risk factors for fecal resistance include coprophagia and previous exposure to fluoroquinolone antimicrobial agents.8

Alternative administration routes (eg, regional limb perfusion) may lower systemic exposure and decrease gut microbiome changes and should be considered when possible.9

Legal Considerations for Use

The Animal Medicinal Drug Use Clarification Act of 1994 specifically prohibits extra-label use of chloramphenicol in food animals.10

Because of the increased popularity of pot-bellied pigs as pets, veterinarians must recognize that all porcine species are considered under federal law as food animals.

This federal law also applies to meat rabbits and backyard chickens, which occasionally may be presented to small animal practices.10