Cerebral Infarction

Mark Troxel, DVM, DACVIM (Neurology), Massachusetts Veterinary Referral Hospital, Woburn, Massachusetts

Profile

Definition

Cerebrovascular disease refers to a group of disorders that result from a pathological process that compromises blood supply to the brain.

Such disorders may be either ischemic or hemorrhagic.

Infarction is a local tissue injury or necrosis from reduced or absent blood flow to a specific part of the body, including the brain.

Cerebral infarction (cerebral infarct, cerebrovascular accident [CVA], or stroke) is usually a focal ischemic event with an acute onset of asymmetric clinical signs that are progressive for a short time.

Global brain ischemia can also occur (eg, anesthetic accidents, cardiopulmonary arrest).

By definition, clinical signs must be present for at least 24 hours to be considered a stroke.1,2

Transient ischemic attack (TIA) is the term used to describe a cerebrovascular disorder in which clinical signs resolve within 24 hours following transient ischemia.

Pathophysiology

There is little energy reserve in the brain, so it is dependent on continuous delivery of oxygen and glucose for energy; it is capable of only aerobic metabolism.1

The brain receives 20% of cardiac output and accounts for 15% of oxygen consumption, despite comprising only 2% of body weight.1

Infarcts can be described based on their underlying pathophysiology or location and size.

Underlying Pathophysiology2,3

Ischemic infarct is secondary to lack of oxygen delivery caused by blood vessel obstruction; this is the most common form of cerebral infarct in dogs and cats.

Hemorrhagic infarct is secondary to ruptured blood vessels leading to hemorrhage within the brain parenchyma.

Location & Size1,3

Territorial infarct is a large area of tissue damage secondary to obstruction of one of the major arteries to the brain (eg, middle cerebral artery, rostral cerebellar artery).

Lacunar infarct is a smaller area of tissue damage from obstruction of small superficial or deep penetrating arteries.

Signalment

Infarction can occur at any age but is typically diagnosed in middle-aged to geriatric dogs and cats.4-6

No apparent gender predisposition.

They can occur in all breeds of dogs and cats, but the following breeds may be at increased risk6-10:

Greyhounds: Especially cerebellar infarcts; these are often idiopathic but may be hypertension-related.

Cavalier King Charles spaniels: Possibly related to local alterations in intracranial pressure secondary to Chiari-like malformation.

Miniature schnauzers: Possibly related to hyperlipidemia.

Brachycephalic breeds: Increased risk for global ischemia, especially with ketamine anesthetic protocols.

Risk Factors

The three most common risk factors for cerebral infarction are hypertension, hypercoagulability, and hyperviscosity.

Predisposing Conditions2,4,6,11

The most common predisposing causes are idiopathic hypertension, chronic kidney disease, and hyperadrenocorticism.

A predisposing condition is identified in just over half of dogs with MRI evidence of infarction.

See Predisposing Conditions for Cerebral Infarction.

Predisposing Conditions for Cerebral Infarction

Aberrant parasite migration (eg, Cuterebra spp, Dirofilaria immitis)

Angiostrongylus vasorum infection

Atherosclerosis

Cardiac disease

Coagulopathy

Chronic kidney disease

Extension of CNS infection

Hyperadrenocorticism

Hyperlipidemia

Hypertension

Hypothyroidism

Increased blood viscosity (eg, polycythemia, multiple myeloma)

Intravascular neoplasia (eg, lymphoma, hemangiosarcoma)

Liver disease

Protein-losing nephropathy

Sepsis and bacterial thromboembolism

Vasculitis

History

Patients are usually presented for evaluation following peracute to acute onset of neurologic signs that are non-progressive after 24 hours.

Rarely, progression may occur at 48-72 hours because of secondary cerebral edema.1,2

Common clinical signs noted by owners include vestibular dysfunction, seizures, altered mental status, paresis, or ataxia.

Physical Examination

General examination may be normal or demonstrate changes consistent with a predisposing condition (eg, cranial abdominal organomegaly, thin hair coat).

Retinal fundic examination is recommended.

Hypertension may cause enlarged or tortuous retinal vessels.

Papilledema may be present if increased intracranial pressure.

Concurrent chorioretinitis or infiltrative disease (eg, lymphoma)further suggests presence of a concurrent, predisposing condition.

Neurologic Examination

As with all neurologic disorders, neurologic signs reflect lesion location and extent rather than cause.

Common signs based on lesion location include:

Cerebrum: Seizures, mental obtundation, circling, pacing, inappropriate elimination

Thalamus: Signs of cerebral disease as above or vestibular dysfunction (possibly from damaged thalamic relay centers associated with cerebellar and vestibular nuclei; damage to the medial longitudinal fasciculus; input of vestibular information to the thalamus; or diaschisis, a sudden change in function in one area of the brain from damage in a distant location).

Brainstem: Altered mental status, cranial nerve deficits, vestibular dysfunction, paresis, ataxia.

Cerebellum: Paradoxical central vestibular dysfunction, hypermetria, cerebellar (intention) tremors, truncal sway/ataxia.

Diagnosis

Definitive Diagnosis

Definitive diagnosis requires histopathology at necropsy.

CT- or MRI-guided stereotactic biopsy may not provide a definitive diagnosis of infarction but may help rule out other possible causes (eg, neoplasia, encephalitis).

A presumptive diagnosis can be made via advanced imaging and exclusion of other potential causes.

Differential Diagnoses

Intracranial neoplasia

Immune-mediated, non-infectious encephalitis (eg, granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis, necrotizing encephalitis)

Infectious encephalitis

Traumatic brain injury

Laboratory Findings

Minimum database includes CBC, serum chemistry panel, thyroid hormone analysis, and urinalysis.

Serial systolic blood pressure measurements should be obtained to rule out systemic hypertension.

Thoracic radiographs and abdominal ultrasound are recommended to screen for neoplasia and predisposing conditions.

Ancillary diagnostics should be performed based on the type of infarction present (Table 1).

Table 1: Ancillary Diagnostics

Imaging

MRI is the advanced imaging modality of choice given its superior soft tissue resolution.

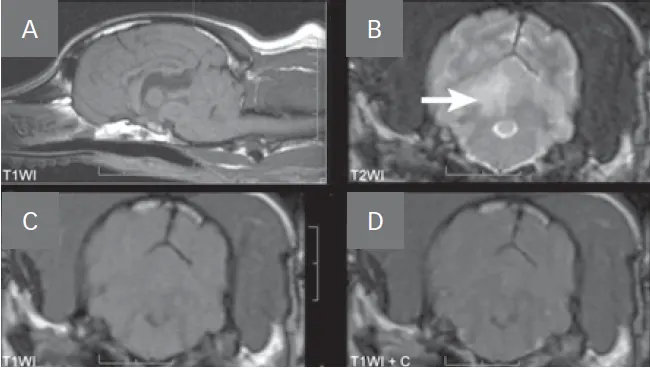

The classic MRI characteristic of an ischemic stroke (Figure 1, see image gallery below) is an intra-axial lesion (often wedge-shaped) that is hyperintense (bright) on T2-weighted and fluid attenuation inversion recovery (FLAIR) images, iso- to hypointense (dark) on pre-contrast T1-weighted images, and minimal to no contrast enhancement.

Diffusion weighted imaging (DWI; Figure 2, see image gallery below) is the sequence of choice for acute ischemic infarction.

DWI detects lack of normal Brownian motion of molecules, particularly lack of intercellular water movement from cell swelling associated with cytotoxic edema.

An acute infarction appears as a hyperintense region.

The MRI appearance of hemorrhagic infarction (Figure 3, see image gallery below) varies greatly as blood cells and hemoglobin degrade (Table 2).

Hemorrhagic infarcts can be difficult to distinguish from hemorrhagic brain tumors (eg, glioma, hemangiosarcoma).

The T2*-gradient echo (T2*GRE) sequence is best for identifying hemorrhage as it is hypointense on this sequence.

T2*GRE is also hypointense for mineralization, air, iron, melanin, and foreign bodies.

FIGURE 1

MRI images of a dog with a right cerebellar infarct (A). Note the wedge-shaped intra-axial lesion in the right dorsal cerebellar gray matter (arrow) that is hyperintense on T2-weighted images (B), isointense on T1-weighted images (C), and does not contrast enhance (D).

Table: MRI Characteristics of Hemorrhage

Treatment

Inpatient or Outpatient

Patients with mild signs may be treated on an outpatient basis.

Non-ambulatory patients with moderate to severe clinical signs, especially larger-breed dogs, may need to be hospitalized until they are able to walk with minimal to no assistance.

Acute Medical Treatment

In general, there is no specific treatment for cerebral infarction.

So-called clot busters or thrombolytic agents (eg, tissue plasminogen activator [tPA], streptokinase) are frequently used in human medicine.

These medications are infrequently used in veterinary medicine because blood clots are rarely a cause of infarction in dogs and cats, thrombolytic agents need to be given within 6 hours of infarction, and expense or limited availability preclude their use.

Mannitol (0.5-1.0 g/kg IV over 10-15 minutes) or hypertonic saline 7.5% (3-5 mL/kg IV over 10-15 minutes) may be needed to reduce brain swelling.

There is a theoretical risk for exacerbating hemorrhage or cerebral edema if mannitol is given to patients with intracranial hemorrhage, but benefits likely outweigh risks.

Hypertension should be treated to prevent ongoing damage.

Initial treatment recommendations include enalapril (dogs, 0.5 mg/kg PO q12h) or amlodipine (cats, 0.625-1.25 mg per cat PO daily).

Oxygen support is recommended in moderate to severe cases, especially if hypoventilation is present.

Nursing care for recumbent patients is critical and includes frequent turning and thick bedding to prevent pressure sores, urinary catheterization if indicated, and physical rehabilitation (at a minimum, passive range of motion and massage).

Chronic Medical Treatment

Underlying predisposing conditions should be treated as indicated to reduce the risk for future infarction.

Antithrombotics may be considered if a thromboembolic disorder is proven, but their use is controversial and not proven to be beneficial.

Options include clopidogrel (dogs, 1 mg/kg PO q24h; cats, 18.75 mg per cat PO q24h) or aspirin (dogs, 0.5-1.0 mg/kg/q24h; cats, 40 mg [1/2 baby aspirin tab] PO q48-72h

Nutritional Aspects

There are no specific nutritional recommendations for infarction, but diets higher in essential fatty acids and omega-3 may be helpful.12

Diet recommendations should also be based on predisposing conditions, such as a low-protein diet in patients with kidney disease.

Activity

There are no activity restrictions for this condition.

Physical rehabilitation is highly recommended to improve recovery and shorten duration of signs.

Client Education

Clients should be taught how to provide nursing care for recumbent animals, as well as how to treat underlying predisposing conditions.

Follow-up

Patient Monitoring

Patients should be monitored for signs of progression that might be consistent with a diagnosis other than stroke.

If signs are progressive, further examination is required as that would suggest the patient did not have a stroke.

Clients should be instructed to observe for signs of recumbency-associated aspiration pneumonia (eg, coughing, tachypnea, dyspnea).

Complications

The most common complication is recumbency-associated aspiration pneumonia.

Other complications may be observed depending on concurrent predisposing conditions.

In General

Relative Cost

Diagnostic workup and acute treatment: $$$$-$$$$$

Chronic treatment and follow-up: $$-$$$

Cost Key

$ = <$100

$$ = $100-$250

$$$ = $250-$500

$$$$ = $500-$1,000

$$$$$ = >$1,000

(Actual costs will have regional variations)

Prognosis

In general, the prognosis for recovery is good to excellent for patients with focal infarctions that have limited initial clinical abnormalities, if given enough time and supportive care.

Some patients have residual clinical signs, but quality of life is acceptable for most patients.

The prognosis for global brain ischemia is guarded to fair.