The Case: The Worsening Pneumothorax

Barak Benaryeh, DVM, DABVP, Spicewood Springs Animal Hospital, Austin, Texas

Gretchen Statz, DVM, DACVECC, Antech Diagnostics, Veterinary Emergency and Specialty Care, Indianapolis, Indiana

Clinical History

Day 1: An 11.5-year-old male neutered domestic short-haired cat was hospitalized for lethargy and fever. A single dose of clindamycin (11 mg/kg PO) was administered and thoracic radiographs (2 views) were taken. Although they were overexposed, significant elevation of the cardiac silhouette from the sternum was apparent and there was a diffuse increased opacity in the lung fields. The patient became acutely dyspneic several hours later, was diagnosed with pneumothorax based on the radiographs, and was transferred to a referral center for thoracocentesis.

Physical Examination Findings

Temperature: 103.7⁰F

Respiration: 40 bpm (tachypnea) with 2+ respiratory effort and mild abdominal component

Lung sounds: Increased ventrally; quiet dorsally

Heart sounds: Difficult to auscultate clearly

Moderate subcutaneous emphysema/swelling of the left axilla and brachium. No puncture wound found upon shaving

Muscle atrophy palpated along dorsum

Diagnostics

Pulse oximeter: 88%–89% (without oxygen supplementation)

CBC with differential: Within normal limits

FeLV/FIV/heartworm point of care test: Negative

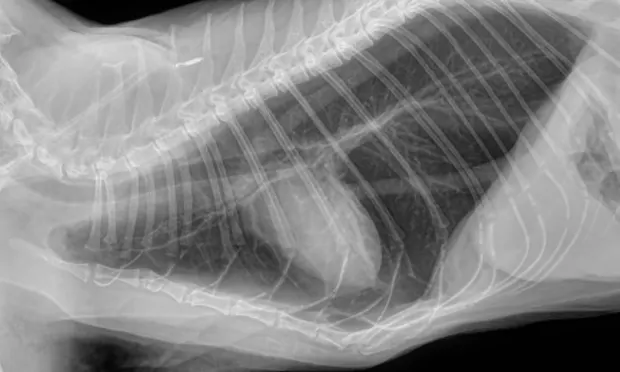

Thoracic radiographs (3 views): Initial interpretation by overnight doctors was significant elevation of the cardiac silhouette from the sternum (moderate pneumothorax); diffuse bronchial pattern; moderate to severe subcutaneous emphysema of the left axilla. (See Radiographs)

Treatment

Initiated hospitalization in oxygen cage with IV catheter

Butorphanol: 0.2 mg/kg IV

Shaved/prepped right and left dorsal thorax and performed thoracocentesis: 108 mL air from L, 380 mL air from R. Afterward, respiration improved, patient became more active and ate well

Plasmalyte*: 1x maintenance rate (2 mL/kg/hr)

Famotidine: 0.5 mg/kg IV

Respiratory rate/effort began to worsen in early morning. Radiologist interpretation of earlier study:

Marked hyperinflation of lungs with diffuse bronchial pattern

Severe subcutaneous emphysema and soft tissue swelling of left axilla/upper forelimb/thoracic body wall

Radiologist interpretation of post-thoracocentesis radiographs: Iatrogenic moderate pneumothorax; condition appeared worse after thoracocentesis than before

Continued Care

Pneumothorax: Monitored; remained static for days before resolving. Another thoracocentesis was not necessary, as patient became eupneic.

Fever: Resolved initially but returned:

Ampicillin: 20 mg/kg q8h IV

Buprenorphine: 0.02 mg/kg q8h IV

Further workup was pursued due to the intermittent fever and the cat’s overall initial presentation to the referring veterinarian.

Thyroxine (TT4): Within normal limits

Abdominal ultrasound: Hyperechoic liver, single hepatic nodule, splenomegaly

Fine needle aspirate of liver performed, cytology pending

Prothrombin time/partial prothrombin time: Within normal limits

A gallop sound noted on cardiac auscultation developed during hospitalization.

Discharge

At-Home Treatment

Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid: 13.75 mg/kg q12h PO

Diphenhydramine: 2 mg/kg q12h PO

Famotidine: 0.5 mg/kg q24h PO

Mirtazapine: 1.88 mg q48h PO

Steroids for treatment of asthma were withheld until liver cytology results became available.

Follow-up

Day 6: The patient returned emergently 2 days after discharge for rapid, shallow breathing and was readmitted. He became eupneic within 24 hours with oxygen support and initiation of steroid treatment for asthma. Cytology from fine needle aspirate of liver revealed hepatocellular vacuolization/possible hepatic lipidosis. The patient was discharged with a prescribed tapering course of prednisolone (0.5 mg/kg q12h PO tapered to lowest effective dose over 4 weeks) and an albuterol inhaler for emergency use.

Day 8: Returned for increased/open-mouth respiration. Intermittent anorexia had also been exhibited since discharge. Admitted for treatment/supportive care.

Radiographs: Persistent hyperinflation but with improvement from initial study

Respiration: Improved

GI signs: Patient vomited/displayed signs of nausea

Heart: Gallop sound persisted. Further diagnostics (heartworm antibody, echocardiogram, tracheal wash) were declined at this time due to financial limitations

Treatment:

Terbutaline: 0.01 mg/kg q8h SC

Doxycycline: 5 mg/kg q12h PO

Maropitant: 1 mg/kg SC (single dose)

Patient’s appetite waxed and waned during hospitalization. He was discharged on prednisolone, famotidine, and mirtazapine as previously prescribed, doxycycline (5 mg/kg q12h PO), and maropitant (1 mg/kg q24h PO) for up to 4 consecutive doses.

Day 10: Cat returned the day after discharge for an echocardiogram and was diagnosed with unclassified cardiomyopathy. Benazepril (0.5 mg/kg q24h PO) and clopidogrel (18.75 mg q24h PO) were dispensed. As the owner had reported a difficult time administering his other medications, only the tapering prednisolone in addition to the heart medications were continued.

Outcome

Patient was doing well at his last recheck but the owner still had some difficulty with medications.

*A multiple-electrolyte solution

The Generalist’s Opinion

Barak Benaryeh, DVM, DABVP

This case exemplifies the difficulties involved in treating dyspneic cats and the complexity of treating feline asthma. It had some confounding factors.

Initial Presentation: The Acutely Dyspneic Cat

The cat initially presented with a fever and lethargy; then developed acute dyspnea while hospitalized. The diagnosis and decision to treat for pneumothorax was an unfortunate misstep. The films taken upon referral are consistent with a bronchial pattern and show evidence of overinflation. Lung tissue is present throughout all lung fields and, although the cardiac silhouette is elevated, this is due to air trapping within the alveoli and not a pneumothorax. In general, a ventrodorsal view is good for confirming the presence of a pneumothorax: there would be black areas where the lung is pulled away from the chest wall as a result of air in the pleural space. In these films, lung tissue can be seen all the way to the edges of the thoracic cavity. As a side note, spontaneous pneumothorax has been reported in asthmatic cats, so it is not out of the realm of possibility.1

Administering oxygen, and butorphanol to minimize stress, were very good first steps as they would be for any cat in respiratory distress.2 Performing the thoracocentesis we now know was an error. If a diagnosis is in question for a dyspneic cat, steps can be taken that will not be harmful and may provide benefit, regardless of the cause: A single dose of furosemide is very rarely harmful and, if the dyspnea is cardiogenic, can be lifesaving. Beta-agonists such as terbutaline or inhaled albuterol are beneficial in emergencies involving inflammatory airway disease such as asthma and would have been helpful in this case. These steps will help in the acute phase for many cats with dyspnea until a definitive diagnosis can be reached and will generally do no harm.

Discharge & At-Home Treatment

The patient was discharged with antibiotics, an antihistamine, an H2 blocker, and an appetite stimulant. Steroids for asthma were withheld until liver cytology results were obtained. This was not an unreasonable approach but, considering the severity of the asthma attack, it would have been prudent to include medication to help control airway disease. A good alternative to oral steroids might have been an inhaled steroid such as fluticasone, which has a slower onset than oral steroids but fewer systemic side effects.

Follow-up Presentations

At the follow-up visit, oral steroids as well as an albuterol inhaler for emergency purposes were introduced. The diagnosis of unclassified cardiomyopathy helps explain why this cat’s airway disease was so difficult to control. Airway disease in cats can be difficult to manage in itself; any cardiac component will obviously complicate things. Some additional strategies that might have been considered are, again, a fluticasone inhaler and management of the cat’s environment. It is always worth mentioning to owners that using higher-rated house air filters, changing them often, and considering a HEPA filter for the house may benefit asthmatic cats.

Cats in respiratory distress tend to present more of a challenge than their canine equivalents. Heart disease in cats is less obvious radiographically (as was demonstrated here). Familiarity with emergency management of dyspnea as well as recognizing the described radiographic conditions will help in the successful management of such patients.

Despite all this, we all have our moments of making the wrong call. These clinicians did a good job of pulling this cat through a difficult case with a bad beginning. How we manage ourselves when things don’t go well reflects on our character as people and clinicians.

The Specialist’s Opinion

Gretchen Statz, DVM, DACVECC

The main problem with this case was the misdiagnosis of pneumothorax by multiple veterinarians. The primary veterinarian referred the patient specifically for thoracocentesis because he or she suspected pneumothorax, and this incorrect thought process was continued at the referral center––an example of "diagnosis momentum.” It is easy to develop tunnel vision when a patient presents with a diagnosis already made, even if it is incorrect, illustrating the importance of forming your own problem list and plan.

Radiographic Interpretation

Pneumothorax was diagnosed here based on the elevation of the heart from the sternum, which can be one of the signs of pneumothorax. However, it is extremely important to look at the entire radiograph. In these, (see images) the lung fields can be followed to the edge of the chest cavity on both the lateral and ventrodorsal views: there is no air surrounding the lung lobes. Although the heart looks raised, the area ventral to the heart on the lateral images shows a soft tissue opacity (possibly fat), not air. The lungs are hyperinflated, which is consistent with primary lung disease and not a typical sign of pneumothorax.

It was misleading that air was obtained through thoracocentesis and the cat initially seemed to respond. The air removed is presumed to be secondary to centesis of lung tissue; the initial improvement in respiratory effort may have been secondary to the butorphanol and sedation rather than the chest tap itself. The pneumothorax that occurred after the thoracocentesis likely resulted from puncture of the lungs. Pneumothorax is a rare complication of thoracocentesis or lung aspiration.

Subcutaneous Emphysema

The cause of the subcutaneous emphysema was not determined. It is not stated in the history whether this cat goes outside or there are other cats in the house, so the likelihood of trauma is not known. It is possible that there were gas-producing bacteria causing the subcutaneous emphysema, lethargy, and fever. The other problems (heart disease, lung disease, liver disease) may have been chronic problems that were discovered as a result of the workup. It is not noted on follow-up whether the emphysema resolved.

Pulmonary Disease

The hyperinflated lungs and bronchial pattern in the radiographs are consistent with primary pulmonary disease. Possible causes could include feline asthma, parasitic disease such as heartworm or other infestation, or toxoplasmosis. An endotracheal wash with cytology and culture, fecal testing (Baermann), and toxoplasma testing would all be considerations. A heartworm test that was performed was negative.

Fever of Unknown Origin

Fever of unknown origin can be very challenging. Basic diagnostics could include complete blood count/chemistry profile, urinalysis with culture, chest radiographs, abdominal ultrasound, and infectious disease testing (FeLV/FIV, toxoplasmosis, etc). In this case, I might have pursued further workup for the subcutaneous emphysema (fine needle aspirates, exploration with biopsy/culture) in addition to the diagnostics performed. It is not stated whether a serum chemistry profile was performed and whether liver values were elevated. Another consideration would be endotracheal wash with culture to detect possible lung infection.

Medical Management

In my opinion, medical management in this case was appropriate. Gas-producing bacteria could include Clostridium spp, which should respond to amoxicillin/clavulanic acid. Because the owners declined further diagnostics for the pulmonary disease, presumptive treatment for feline asthma seems reasonable. Inhaled steroids may have been a better long-term option since oral medication was difficult for these owners to administer.