Canine Neck & Back Pain

Theresa E. Pancotto, DVM, MS, DACVIM (Neurology), CCRP, Specialists in Companion Animal Neurology; Naples, Florida

How would you approach this case of severe canine IVDD? Find tips for effective medical management when surgery is not an option.

Case Summary

Theresa Pancotto, DVM, MS, DACVIM (Neurology), Virginia–Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine

Copernicus is a 4-year-old castrated dachshund. His owner, Mrs. Bruno, noticed his back legs were a little wobbly when she walked him. He refused to climb the stairs into the house but ate normally. When Mrs. Bruno picked him up to put him in his crate, he tried to bite her and attempted to run away but could not walk.

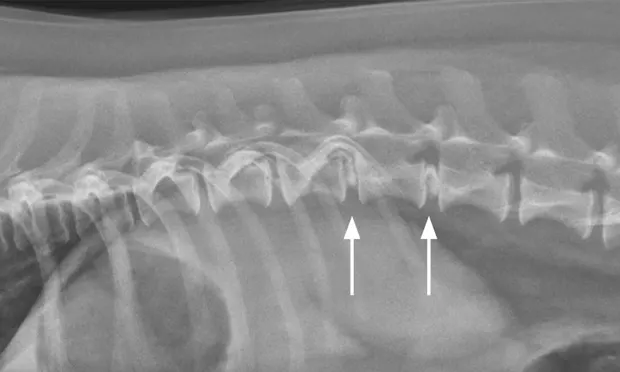

Lateral spinal radiograph. Mineralization and narrowing of the T13-L1 and L1-L2 disc spaces was noted (arrows).

Physical examination was unremarkable except for a BCS of 6/9. On neurologic examination, Copernicus could support weight only when standing with assistance; he fell when attempting to walk, although he was able to move both pelvic limbs when sling-walked. Proprioceptive response tests while Copernicus was sling-supported showed he had normal thoracic limbs, but he did not replace either pelvic limb when the foot’s dorsal surface was placed back down.

When Copernicus’ weight was shifted from right to left, he had a delayed hopping response in the right leg and no response in the left. His withdrawal reflexes in response to toe pinching were intact. The panniculus reflex was absent caudal to the thoracolumbar (TL) junction, where palpation elicited pain.

VD spinal radiograph. Mineralization and narrowing of the T13-L1 and L1-L2 disc spaces was noted (arrows).

The problem list noted:

P1: Focal T3-L3 myelopathy, grade 3/5, slightly worse on the left

P2: Overweight

Differential diagnoses:

Type I intervertebral disc disease (IVDD)

Fibrocartilaginous embolism

Complicated discospondylitis

Meningomyelitis

Neoplasia

Fracture/luxation.

The suspected cause was IVDD. Because Copernicus could not walk, referral to a surgeon was strongly recommended. However, Mrs. Bruno said her husband had recently lost his job and they could not afford surgery. Spinal radiographs were recommended instead to rule out diseases that would change the surgery recommendation.

The veterinarian administered 0.02 mg/kg acepromazine IM and 1 mg/kg morphine IM1 and obtained lateral and VD views of the TL vertebral column. (See Figures 1 & 2.) The radiographs showed no evidence of lytic change but did show mineralization and narrowing of the T13-L1 and L1-2 intervertebral disc spaces (arrows).

Related Article: Tools for Talking to Your Clients About Money

Discussion

Theresa Pancotto, DVM, MS, DACVIM (Neurology), Virginia–Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine

Canine IVDD is the most common underlying cause of spinal cord pathology in the dog.2,3 Two types (ie, chondroid, fibrinoid) of degenerative disc change occur, leading to spinal cord compression with acute-to-chronic clinical signs of myelopathy (eg, hyperesthesia, ataxia, weakness, paralysis, loss of deep pain perception, respiratory failure in some cases).

Chondroid metaplasia (ie, Hansen Type I IVDD), most common in chondrodystrophic breeds, is usually associated with nucleus pulposus extrusion and acute onset of clinical signs. The most susceptible breed, the dachshund, is commonly affected between 4 and 6 years of age.2,4,5

Large breeds (eg, German shepherd dogs, basset hounds, Labrador retrievers, Doberman pinschers) may also be affected.5-7 Fibrinoid metaplasia (ie, Hansen Type II IVDD) occurs in any breed and is more commonly associated with intervertebral disc protrusion and chronic clinical signs.4,5,7,8

Related Article: How to Implement a Physical Rehabilitation Program into Your Practice

Neurologic deficits result from spinal cord damage from either compression or contusion. Clinical signs reflect the injured area. T10-L2 intervertebral discs are the most commonly affected in the TL region.5-7 The C2-3 disc is the most common disc to herniate in the cervical region,9 but more than 50% of cervical disc extrusions occur caudal to C4-5. Various scales for grading the severity of spinal cord injury signs are available and usually range from 1 to 5 (see Table 1).10-12

Spinal Cord Injury Scale10,11

Because acute disc extrusions can result in paralysis, differentiating the presence or absence of nociception (ie, deep pain perception)—usually by placing a pair of hemostats across the digit and applying increasing pressure until the patient consciously responds—is critically important. The patient’s response may manifest as crying, biting, or attempting escape from the examiner. Flexion (ie, withdrawal) of the limb is a local spinal cord reflex and not indicative of intact nociception.

Radiographs are not diagnostic for IVDD but can be useful for ruling out other diseases with similar clinical signs (eg, discospondylitis, osseous neoplasia, fracture/luxation). They may also provide supportive evidence, including narrowed intervertebral disc space, in situ intervertebral disc mineralization, opacification of the intervertebral foramen, and/or wedging of the articular facets.13 Spondylosis, which may also be seen radiographically, is thought to be associated with some factors that predispose to disc extrusion or protrusion (eg, biomechanical stress) but has no direct link with clinical signs.14,15

Treatment

_Theresa Pancotto, DVM, MS, DACVIM (Neurology), Virginia–Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine .cc-sectionWrap {overflow: initial !important; }_

Patients that cannot walk voluntarily (ie, grades 3-510,11) should be considered surgical emergencies until proven otherwise, although financial circumstances may dictate medical management of even the most severe cases. Nonambulatory dogs that do not undergo surgery likely will recover more slowly and less completely, and have a higher risk for recurrent clinical signs.16,17 Patients with absent nociception are at risk of developing life-threatening myelomalacia.18 (See Table 2.)

Prognosis for Improvement of Clinical Signs for Thoracolumbar IVDD20

Related Article: When Should You Refer?

Additional reasons to refer for imaging and surgical consultation include failure to improve, worsening during medical management, refractory pain (ie, pain requiring 3 or more medications to temper or that does not resolve in 2 to 4 weeks), or rapid progression of clinical signs. The sooner the referral, the better the prognosis.

If medical management is deemed necessary despite a presumptive IVDD diagnosis, treatment should be initiated with the goals of alleviating pain, decreasing inflammation, managing urinary continence, and preventing decubitus ulcers and further disc extrusion. Because of the presumptive diagnosis, choosing medications that benefit the patient but are not contraindicated or that mask a more sinister underlying condition is important.

Although Copernicus was severely affected and in great pain, surgery was not an option because of the owner’s financial constraints. Manual bladder expression likely was necessary given the severity of signs. At-home management was possible, but his best option was hospitalization to begin therapy and evaluate his treatment response.

IVDD patients require multimodal pain management. Pain control options include:

Intermittent injection or CRI of opioids during hospitalization

Tramadol, although its bioavailability in dogs is variable1

Gabapentin, which has the least immediate effect19 but may help manage chronic pain

NSAIDs

Amantadine for chronic pain

Oral corticosteroids, which are prescribed by some practitioners but are controversial because limited prospective controlled data about their efficacy is available

Acupuncture, which can also be useful in pain management.20

Copernicus was managed with an additional dose of morphine, tramadol (4 mg/kg PO 3 times a day), carprofen (2.2 mg/kg PO twice a day), and gabapentin (10 mg/kg PO twice a day).1

The bladder should be palpated 2 to 3 times daily and expression attempted if the bladder is large and the patient is not urinating voluntarily. In male dogs, passing a red rubber catheter twice a day if the bladder cannot be expressed and medicating the patient to facilitate manual evacuation is warranted; in female dogs, an indwelling catheter may be necessary. Finding urine in the cage or on the dog may not mean the dog is urinating voluntarily—this may be an overflow of an upper motor neuron bladder or incontinence. The patient should be witnessed urinating a normal stream and the bladder should be small on palpation. Catheterization may help reduce patient stress and minimize discomfort for the first day or two. Intermittent catheterization is preferred because the incidence of UTI is lower compared with an indwelling catheter.21

Skeletal muscle relaxants (eg, diazepam, methocarbamol) may relieve muscle spasms and assist in urinary management by relaxing the abdominal wall and external urethral sphincter. Alpha-antagonists (eg, phenoxybenzamine, prazosin) promote internal sphincter relaxation that facilitates manual bladder evacuation.

For medically managed patients, strict cage rest is most important because rest allows time for any annulus tears to heal so that additional nucleus pulposus does not extrude. These inactive patients, particularly those that are weak and not able to fully evacuate their bladder, are predisposed to decubital ulcers and UTIs and must be kept clean and dry on well-padded bedding.

Bladder management is critical because failure to regain urinary continence has a significant impact on patient and client quality of life. Teaching the client such management requires a great deal of patience, but its importance must be emphasized.

The veterinarian also should discuss the prognosis with the client. Up to 85% of dogs22 with grade 3 spinal cord injury from type I IVDD respond to conservative therapy; however, recovery is generally slower and less complete,16,17 and recurrence rates are higher than with surgery.<sup23 sup>

Conclusion

Theresa Pancotto, DVM, MS, DACVIM (Neurology), Virginia–Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine

At his 2-week progress examination, Copernicus was able to support weight on both pelvic limbs and walk, although he was still ataxic and weak. His pain was well-controlled and medications were decreased over the next 2 weeks. At his 4-week progress examination, he was able to ambulate strongly and was taken off all pain medications. Slight ataxia persisted and proprioceptive deficits were still present in both pelvic limbs, so the Brunos prevented any high-impact activity, including jumping, but took him on controlled leash walks 3 times a day. They also added ramps so that Copernicus could get on the furniture without jumping.

Related Article: Pain Management & Mobility in Pets

At Copernicus’ annual examination, some mild deficits persisted but his quality of life was excellent and he had no recurrent problems.