Canine Insulinoma

Christine Mullin, VMD, DACVIM (Oncology), BluePearl Pet Hospital, Malvern, Pennsylvania

Craig A. Clifford, DVM, MS, DACVIM (Oncology), BluePearl Pet Hospital, Malvern, Pennsylvania

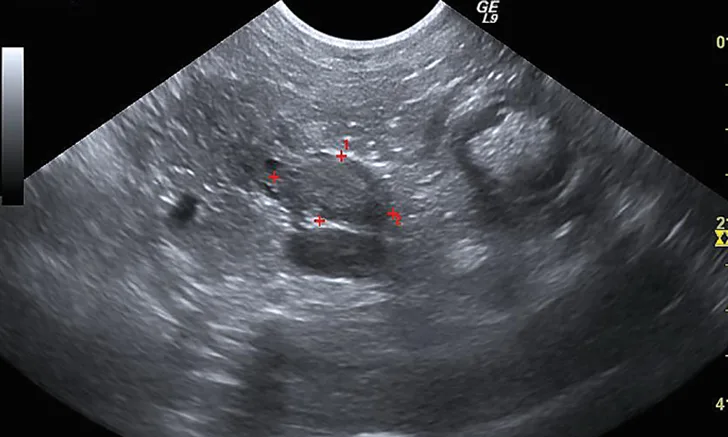

Figure 1 Sonographic image of the nodule at the base of the left lobe of the pancreas (outlined by red markers)

June, a 7-year-old spayed Boston terrier, was presented to an emergency service for acute onset of cluster seizures.

History

The morning of presentation, June had 2 generalized seizures (each lasting ≈20 seconds) 1 hour apart. She had a third seizure 2 hours after the second, shortly followed by an episode of melena, then a fourth seizure 1 hour later. At that time, she was brought to the hospital.

Before the seizures, June had been healthy. She had no changes to appetite, demeanor, or mentation, and she had no other abnormal neurologic signs. She was not on any medications, and her owner reported no evidence of toxin ingestion, trauma, or recent dietary changes. On presentation, June appeared clinically normal; she was up to date on all vaccinations and consistently received heartworm and flea/tick preventives.

Baseline Emergency Diagnostics

Glucose: 51 mg/dL (2.83 mmol/L) (normal, 74-143 mg/dL [4.11-7.94 mmol/L])

Alanine aminotransferase: 267 U/L (4.46 μkat/L) (normal, 10-125 U/L [0.17-2.09 μkat/L])

| | Glucometer | Glucose: 40 mg/dL (2.22 mmol/L) (normal, 70-138 mg/dL [3.89-7.66 mmol/L]) | | Blood pressure | Within normal limits | | Cursory ultrasound (aFAST/tFAST) | No free fluid in either body cavity | | Baseline cortisol | Within normal limits (1.6 µg/dL [44 nmol/L]; normal, 1.0-5.0 µg/dL [28-138 nmol/L]) |

Physical Examination & Diagnostics

On initial evaluation, temperature (100.2°F [37.9°C]), pulse (116 bpm), and respiratory rate (36 breaths/minute) were normal. No significant abnormalities were noted on physical examination. Baseline emergency diagnostics were performed (Table 1); hypoglycemia was the most notable finding.

Differential diagnoses considered for June’s hypoglycemia-induced seizures included toxin (eg, xylitol) ingestion, hepatic insufficiency, and hypoadrenocorticism; however, these were not supported by history, blood work, cortisol level, or clinical presentation. Other differential diagnoses included an insulin-secreting tumor (ie, insulinoma) and a paraneoplastic syndrome (possible with hepatoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, leiomyosarcoma, and [less likely] other cancers).1

Additional diagnostics were pursued. Abdominal ultrasonography demonstrated an ill-defined and mildly hyperechoic 0.75 × 1.37-cm nodule at the base of the left lobe of the pancreas (Figure 1). Small, well-defined hyperechoic nodules were also found scattered throughout all liver lobes. Three-view thoracic radiographs revealed no significant abnormalities.

Because of the suspicion of a possible insulin-secreting pancreatic tumor, paired insulin and glucose levels were submitted to a reference laboratory. Insulin levels were 53.5 μIU/mL (372 pmol/L) (normal, 5-20 μIU/mL [35-139 pmol/L]); glucose levels were 30 mg/dL (1.67 mmol/L) (normal, 70-138 mg/dL [3.89-7.66 mmol/L]). These results confirmed an insulinoma.

Related ArticlesAnesthesia for Pancreatic DiseaseSeizures, Lethargy, & Collapse in a DogPancreatic Biopsy

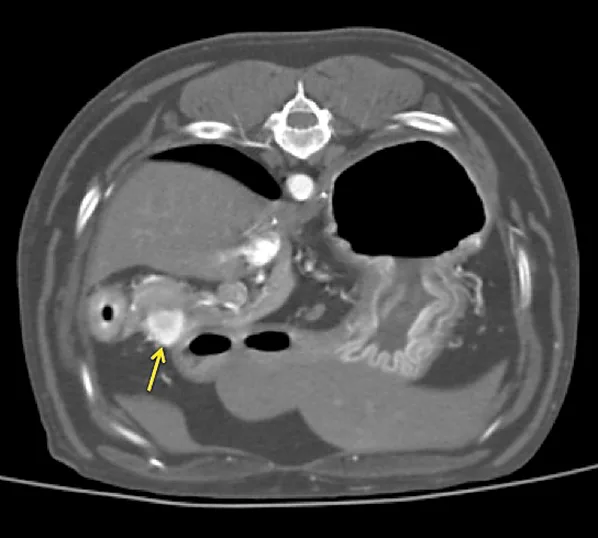

A thoracoabdominal dual-phase CT scan was performed with the goals of further evaluating the pancreatic nodule, ruling out obvious metastatic disease, and planning for possible surgery. The CT scan revealed a 1.8 × 2.6-cm nodule in the body of the pancreas that demonstrated marked neovascularization in the early arterial phase and mild peripheral contrast enhancement relative to the remainder of the pancreas in the main arterial and portal phase scans (Figure 2). A strong contrast-enhancing liver nodule was noted in the arterial phase of the CT angiogram (Figure 3). Other hepatic nodules noted on ultrasound were not visualized in the arterial or mixed portal/venous angiographic phases. No evidence of nodular pulmonary metastasis was evident.

Figure 2 Arterial phase CT angiograph image demonstrating a strongly contrast-enhancing pancreatic nodule (arrow)

Diagnosis & Treatment

June was presumed to have an insulinoma with probable metastasis to the liver. Exploratory laparotomy for resection of the pancreatic mass and hepatic nodule(s) was discussed but was declined by the owner. Ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of the pancreatic mass was performed, and cytology confirmed a neuroendocrine neoplasia consistent with an insulinoma. Specific anticancer therapies were discussed but were declined in favor of starting empiric medical management with dietary therapy (4-6 small meals per day of boiled chicken and turkey plus a prescription fiber-balanced diet) and corticosteroids (prednisone [1 mg/kg q24h]) for their gluconeogenesis effect. June’s quality of life was well managed with this regimen for approximately 6 months, at which time recurrence of hypoglycemic seizures prompted the decision for humane euthanasia.

Treatment at a Glance

Surgery is associated with potential complications but offers the best chance at long-term disease control.2,3,6,7

Dogs with lower-stage disease typically have longer survival times than do those with metastatic disease.8

Medical management is aimed at hypoglycemia control and is recommended for dogs with metastatic disease or for which the owners decline surgery.

Data regarding chemotherapy for canine insulinomas are limited8,10,11; however, recent anecdotal evidence suggests that use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors may hold promise.12-14

Discussion

Insulinomas are functional tumors of pancreatic β cells in the islets of Langerhans that inappropriately secrete insulin without regard for normal inhibitory signals. Most canine insulinomas are malignant and thus carry a risk for metastasis.2,3 Predisposed breeds include German shepherd dogs, boxers, golden retrievers, and Labrador retrievers.3 Clinical signs may be episodic, are typically attributable to hypoglycemia, and can include seizures, weakness, collapse, ataxia, posterior paresis, muscle fasciculations, and peripheral neuropathy.

An insulinoma should be highly suspected when clinical signs are supported by concurrent hypoglycemia (ie, blood glucose concentration <60 mg/dL [<3.33 mmol/L]) and hyperinsulinemia (ie, blood insulin concentration >20 μIU/mL [>139 pmol/L]).3 Blood glucose and insulin levels should be analyzed from the same blood sample.

Canine Insulinoma Staging

Stage I: Insulinoma confined to the pancreas

Stage II: Insulinoma with metastasis to the regional lymph nodes

Stage III: Insulinoma with metastasis to distant organs

Abdominal imaging is recommended for diagnosis and staging of metastatic disease. Although ultrasonography is a commonly available diagnostic tool, insulinomas are often small and difficult to identify on ultrasound. Advanced imaging, particularly dual-phase CT angiography, has been described for detecting canine insulinomas and appears more sensitive than ultrasonography.4,5 Three-view thoracic radiography or thoracic CT is recommended to screen for pulmonary metastasis.

Surgical resection is often the treatment of choice to reduce the burden of disease. Most insulinomas are small and solitary; however, if multiple and diffuse insulinomas have been reported, the entire pancreas should be palpated. Postoperative complications are relatively common and can include pancreatitis, persistent hypoglycemia, transient hyperglycemia, and diabetes mellitus.

For patients with inoperable tumors (ie, advanced disease, widespread metastasis), palliative therapies aimed at controlling blood sugar and slowing tumor growth and metastasis are recommended (Table 2).

Treatment Options for Advanced Insulinoma

Small meals high in protein, fat, and complex carbohydrates and low in simple sugars should be fed 4-6 times per day to prevent spikes in insulin secretion by the tumor and to provide sufficient calories at frequent intervals.2,3

Glucocorticoids are used to increase blood glucose levels by causing insulin resistance and hepatic gluconeogenesis. The recommended starting dose is 0.5-1 mg/kg PO q24h.2,3

Diazoxide, a nondiuretic benzothiadiazine derivative, increases blood glucose through multiple mechanisms. The recommended starting dose is 5 mg/kg PO q12h, but it can be increased to 30-60 mg/kg PO q12h.2,3,15,16

Octreotide is a somatostatin analog that causes hyperglycemia through its inhibitory effects on growth hormone, insulin, glucagon, and gastrin. Reported doses range from 10-50 µg SC q8-12h.3,17

| | Systemic treatment |

Streptozotocin is a nitrosourea chemotherapy agent used for nonresectable and metastatic insulinomas in humans and has been evaluated for use in dogs with insulinoma. It was previously considered an unfavorable option for use in dogs because of the high frequency of severe nephrotoxicity seen in initial investigations; more recent study protocols have incorporated concurrent aggressive saline diuresis, which appears to reduce the frequency and severity of nephrotoxicity. Other reported adverse effects include acute emesis and diabetes mellitus.8,10,11 In a study of 17 dogs,10 2 dogs showed measurable reduction in tumor size with streptozotocin. Because there have been no large-scale studies with standardization of patient groups, the true benefit and best use of this agent remain unclear. Due to the ongoing question of benefit and considerable risk for adverse effects, streptozotocin use in veterinary medicine remains limited.

Toceranib phosphate is a receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor that is FDA labeled for advanced canine mast cell tumors but has shown benefit in treating other (eg, neuroendocrine) tumors.12 Similar molecularly targeted drugs have shown promise for endocrine pancreatic cancer in human oncology.13,14 There are no published studies evaluating the efficacy of toceranib phosphate for canine insulinoma; however, there is anecdotal evidence of clinical benefit reported among veterinary oncologists, including the authors.

|

Prognosis & Outcome

Surgical tumor excision is associated with superior survival times as compared with medical therapy alone.3,6,7 Older studies suggest median survival times of 12 to 14 months for dogs treated with partial pancreatectomy.2,3,6 In one study, dogs undergoing surgery survived longer (median, 381 days) than did dogs undergoing medical therapy only (median, 74 days).6 Another study of 28 dogs found that dogs undergoing partial pancreatectomy (n = 19) survived a median of 785 days, whereas those receiving medical therapy only lived a median of 196 days.7 Of note, a subset of dogs in this study received corticosteroids following relapse and had surprisingly long survival times (1316 days); this has not, however, been the experience of the article authors.7

Postoperative prognosis depends on stage of disease; one study found that the median disease-free interval (ie, duration of normoglycemia) for dogs with stage I disease was 14 months, whereas less than 20% of dogs with stage II and stage III disease had control of hypoglycemia for that length of time, and less than 50% of dogs with stage III disease lived longer than 6 months.8 More recently, certain clinicopathologic features and markers of proliferation were found to be prognostic in a study of 16 dogs in which stromal fibrosis in tumors was found to be significantly predictive for survival, whereas tumor size, the Ki67 index, and TNM (tumor, node, metastasis) were significant for both disease-free interval and survival time.9

Take-Home Messages

Insulinoma is a neuroendocrine carcinoma of the pancreatic islet β cells.

Clinical signs secondary to hypoglycemia are the most common presenting complaints.

An insulinoma should be highly suspected in cases with concurrent hypoglycemia and hyperinsulinemia.

Surgery offers the best chance for long-term control, but medical management may help control clinical signs for prolonged periods.