Canine Influenza

Jarod M. Hanson, DVM, PhD, DACVPM, DABT, University of Maryland

Danielle Dunn, DVM, University of Georgia

Corry K. Yeuroukis, DVM, University of Georgia

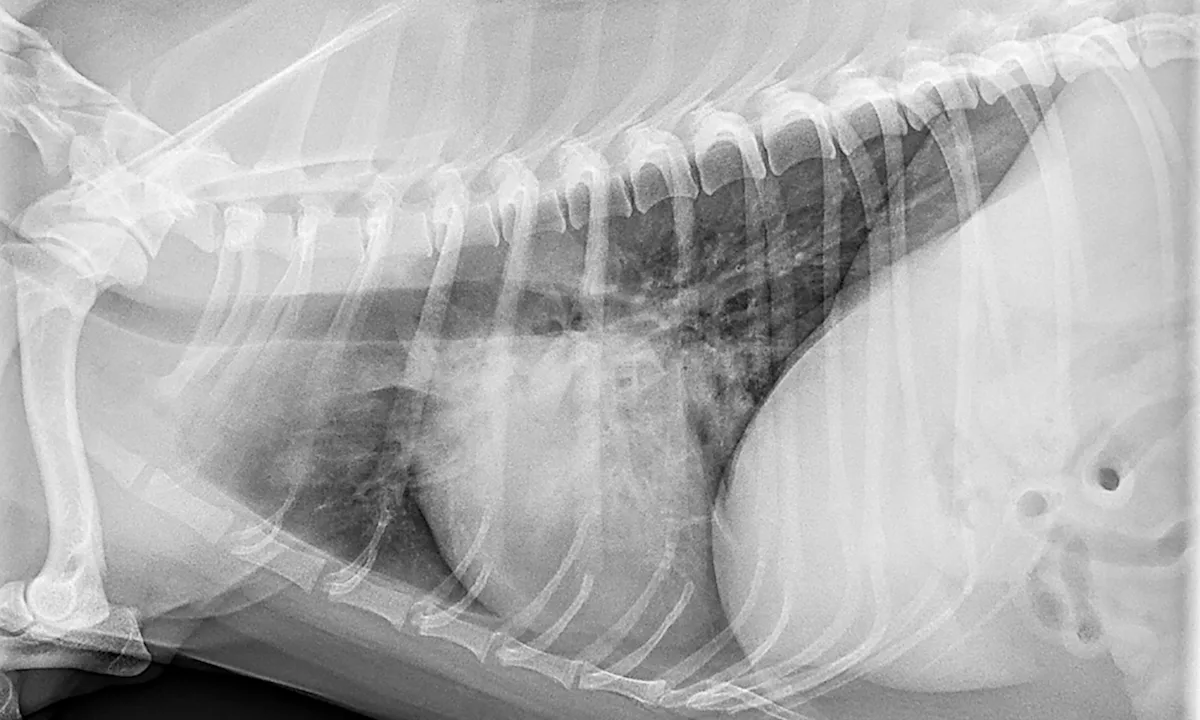

Photo courtesy of Scott Secrest, DVM, MS, DACVR

Profile

Definition

Canine influenza virus (CIV) infection is primarily caused by 2 influenza A virus subtypes: the historical equine-origin H3N8 virus and the recently identified avian-origin H3N2 virus (see Table).

Influenza A virus strains are named after their hemagglutinin and neuraminidase receptors; there are 18 hemagglutinin and 11 neuraminidase variants.

The H3N2 CIV variant was originally identified in dogs in 2007 in South Korea, although subsequent studies indicate the virus circulated as early as 1999.1-3

The H3N8 CIV variant was first identified in Florida in 2004.4

It has persisted primarily in shelter dogs, with sporadic outbreaks elsewhere.5

More recently, dogs, cats, and ferrets have been confirmed to be naturally or experimentally infected with H1N1, H3N1, H3N2, H5N1, H5N2, H5N6, H6N1, or H9N2 influenza A virus strains (Figure).2,6-12

This suggests that the recent emergence and rapid spread of the H3N2 strain in Asia and North America may not be an isolated transmission event and that influenza in companion animals may be underdiagnosed globally.

A serosurvey in cats indicated 22% to 45% prevalence against 3 commonly circulating human influenza strains, further supporting wider exposure of companion species to influenza than previously thought.13

Although the H3N8 and H3N2 CIV variants originated in other species (horses and birds, respectively), both have exhibited limited spread beyond dogs, with the exception of the potential adaptation of H3N2 CIV to cats in Korea and North America (Figure).<sup14 sup>

H3N8 vs H3N2 Canine Influenza

Incidence

Surveillance of dogs in China has shown H3N2 seroprevalence of 5.3% to 12.2%.15

Prevalence in the United States has varied tremendously by location, region, and time of year.<sup16 sup>

The University of Georgia’s Athens Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory reported that 30% of samples submitted for influenza testing through mid-2015 tested positive for the H3N2 variant.17

More recent data from the Canine Influenza Virus Surveillance Network from March 2015 through February 2016 indicate an H3N2 sample positive rate of 11%; however, this likely reflects dogs screened because of the presence of 1 or more clinical signs. Thus, this rate may be higher than would be expected for the entire canine population.16

Representative influenza A strains circulating in canine and feline populations worldwide. Influenza A isolates shown as A/species/country/year isolated/hemagglutinin–neuraminidase subtype, with comments on likely origin in red. Sequences obtained from GenBank. Phylogenetic tree constructed using MEGA6.34

Geographic Distribution

CIV is diagnosed worldwide.

The rapid spread of the H3N2 virus in Asia and the United States indicates this virus is capable of regional epidemics and potentially worldwide pandemics.

Signalment

CIV occurs primarily in dogs, with rare crossover to cats; other species (eg, ferrets) may also be at risk for infection with the H3N2 virus. 2,18,19

Zoonotic transmission has not been observed, and the risk for this type of event appears low.20,21

Transmission of H3N2 CIV from dogs to cats was demonstrated in 2012 and resulted in 100% morbidity and 40% mortality.2

A Chinese study reported a 0.7% prevalence in cats, which indicates ongoing exposure with unknown clinical disease.22

Influenza in cats typically occurs without clinical signs; however, nonspecific upper respiratory tract infections as well as hypersalivation have been reported.14

The canine H3N2 virus has evolved in cats, producing a distinct virus lineage in feline populations (Figure).19

Ferrets have been infected experimentally via direct inoculation and could spread the virus laterally among one another but were resistant to infection from other species through direct contact.11,18

No breed or sex predilection exists.

CIV can affect dogs of any age; younger and older dogs may be more likely to experience severe cases because of poor immunocompetence and immune senescence, respectively.23

Other risk factors include administration of immunosuppressive drugs and exposure to crowded environments.24

Exposure to high-population locales (eg, shelters, boarding facilities, dog parks, grooming facilities) may also increase risk for infection.

Transmission Cycle

Transmission occurs primarily via infectious aerosols, fomites, and direct contact.

Infection occurs within hours, with the virus initially multiplying in respiratory epithelial cells.

Shedding occurs for up to 10 days for H3N8 and up to 24 days for H3N2 and often begins before clinical signs are apparent.25

Pathophysiology

Influenza replication occurs almost exclusively in epithelial cells lining the respiratory tract.

Damage to lung tissue can take weeks to resolve and can lead to chronic cough even after the animal is no longer viremic.

History

Often consistent with risk factors noted previously

Patients from single-animal households are not immune, as infection can occur via fomites or incidental exposure to infected dogs.

Clinical Signs

Some animals remain clinically normal following infection, so CIV should remain a differential for generalized respiratory disease even if other animals in the same location appear unaffected.

The severity of infection is variable with both H3N8 and H3N2.

Clinical disease is typically self-limiting and mild, although the severity of H3N2 may be greater than that of other canine respiratory etiologic agents in specific cases.26

There is typically a greater incidence of lower respiratory tract involvement with CIV than with other pathogens (eg, canine respiratory coronavirus, parainfluenza virus 5).26

Onset of clinical signs is often rapid (ie, 2-3 days).

Many infected dogs do not show clinical signs; others typically exhibit mild cough, some degree of anorexia, lethargy, fever, sneezing, nasal discharge (clear to mucopurulent), and/or dyspnea (in severe cases; most often seen with H3N2).

Fever is typically low-grade, if present, and may occur only during the initial days of infection.

Cough can persist for 10 to 14 days and is typically dry, nonproductive, and self-limiting.

Persistent and severe respiratory disease may indicate pneumonia; animals with these signs may have tachypnea, dyspnea, and/or pulmonary crackles.

Diagnosis

Definitive Diagnosis

Virus isolation from deep nasal (preferred), nasopharyngeal, or oropharyngeal swabs or from lung tissue (formalin fixed and fresh) from deceased animals can be performed early in the course of the disease, although H3N8-infected patients may not shed virus after 7 to 10 days.

Bacterial cultures may be indicated if initial supportive treatments fail.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from swabs and/or tissue indicates exposure to influenza A virus (nonspecific).

Virus-specific PCR and/or sequencing of live virus is necessary to delineate between H3N8, H3N2, or another strain.

Serologic testing indicates exposure and is generally not useful during acute disease.

Acute and/or convalescent serum samples for antibody titers indicate exposure to influenza virus if the convalescent sample antibody titer is roughly 4× higher than the acute sample titer.

Positive serologic results from a single chronic sample only indicate exposure and may not allow for definitive diagnosis without an acute titer for comparison.

Differentiating Tests

Other laboratory tests

CBC: Leukocytosis with left shift may be noted in animals that have developed pneumonia. The remainder of the CBC is often unremarkable.

Serum chemistry profile: Changes are nonspecific, but hypoalbuminemia may be seen secondary to protein loss in the pulmonary parenchyma, especially with severe pneumonia.

Blood gas test: Typically unremarkable, but hypoxemia may be seen in more severe cases

Transtracheal wash or bronchoalveolar lavage: Should be used with caution, as it may be contraindicated if the patient exhibits significant respiratory compromise or more severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).27,28

Acute lung injury (ALI) is a syndrome involving pulmonary inflammation and edema that can progress into acute respiratory failure; it is often seen during fatal influenza virus infections.

Severe ALI is often termed ARDS, with the major difference being the degree of hypoxemia present.27

Imaging

Radiographs: Unstructured interstitial, bronchointerstitial, and/or alveolar patterns, depending on pneumonia progression (eg, acute, chronic, resolving)

Postmortem findings

Gross

Areas of red-to-tan severe consolidation28

Bronchointerstitial pneumonia, often cranioventral

May be hemorrhagic in severe cases28

Microscopic

Necrotizing bronchiolitis and/or tracheitis, often suppurative

Loss of Type I alveolar cells

Alveolar thickening due to Type 2 alveolar cell proliferation

Treatment

Most cases of CIV are self-limiting and do not require treatment, but moderate-to-severe cases or those complicated by secondary infections may require further care.

Supportive Care

May include, but is not limited to, IV fluids, supplemental oxygen, and/or an oxygen cage

Inappetence is a common clinical finding; supplemental nutritional support may be indicated if the patient has been inappetent for 3 or more days.

Animals with pneumonia may benefit from nebulization and coupage 3 to 4 times a day.

Medications beyond aerosol therapy are typically not needed.

Medication

Antibiotics: Broad-spectrum antibiotics to treat or prevent infection with secondary bacterial pathogens (eg, Escherichia coli, Pasteurella spp, Bordetella bronchiseptica, or Streptococcus spp) should be considered in mild-to-severe cases, especially if fever, inappetence, or lethargy is present concurrently.

Amoxicillin–clavulanate, azithromycin, doxycycline, and enrofloxacin are commonly used.

Hospitalization and IV antimicrobials may be indicated in severe cases.

Antiviral drugs: Because antiviral drugs must be administered early in the course of infection to be effective, they are of little benefit to most patients. Additionally, the efficacy and safety of these drugs in dogs has not been established.

Because the use of antiviral drugs can lead to development of drug-resistant virus strains, they should be avoided to preserve drug efficacy in humans.29,30

H3N2 CIV has reassorted with human and avian influenza viruses; this indicates that mutations driven by antiviral use could be transferred because of inherent virus compatibility.<sup3,7,31 sup>

Corticosteroids: May be contraindicated; prolonged shedding of higher amounts of H3N2 virus was observed in dogs treated with immunosuppressive doses of prednisolone, which were much higher than the typical anti-inflammatory doses administered in most clinical patients.24

In patients with severe clinical signs (ie, ARDS) or those exhibiting chronic respiratory inflammation, anti-inflammatory doses of steroids may be beneficial.

Antitussives: May be considered as a means to disrupt the cough cycle

Not recommended in patients with bacterial pneumonia, as these drugs may decrease bacterial clearance and cause retention of respiratory secretions

Bronchodilators: Although limited benefit has been observed with these drugs, they can be effective cough suppressants in some cases.

Dose reduction is indicated when using methylxanthine bronchodilators in combination with certain medications (eg, enrofloxacin)

Activity

Activity should be limited; cage rest may be indicated to limit respiratory fatigue.

Dogs should be isolated during the first 21 days, when most viral shedding occurs.

Client education: Most CIV cases occur with no or mild clinical signs; however, it can be fatal, especially the H3N2 variant.

Patients that require hospitalization often fail to recover, most often because of secondary bacterial pneumonia.

CIV is also highly infectious to other dogs (and, in the case of H3N2, to cats), so isolation measures should be encouraged to prevent infection of other susceptible animals.

Follow-Up

Patient monitoring

Oxygen saturation via pulse oximeter can be used to determine discontinuation of oxygen supplementation.

SpO2 ≤93% is indicative of hypoxemia.

Complications

Secondary bacterial pneumonia

Slowly resolving lesions and/or chronic lung scarring may be present.

Infection predisposes affected dogs to secondary viral and bacterial pathogens as a result of pulmonary edema and necrotizing lesions.

ALI, ARDS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, and sepsis

In General

Relative cost

Highly variable depending on complications and/or severity of bacterial pneumonia

Costs are significantly higher for dogs requiring oxygen support, parenteral antibiotics, and/or nutritional support than for those treated as outpatients.

Prognosis

Highly variable depending on age and underlying medical conditions

Although many infected animals remain clinically normal, the most severe cases require aggressive medical treatment to prevent patient death.

Prevention

Licensed vaccines are available (merck.com, zoetisus.com) against H3N8 CIV. Conditionally licensed vaccines (merck.com, zoetisus.com) are available for H3N2 CIV. The vaccines are labeled for use only in dogs and require an initial dose followed by a booster, with annual vaccination recommended thereafter for at-risk dogs. Although vaccination for CIV may not prevent infection, it can help reduce clinical signs and disease severity and may reduce viral shedding. This can help minimize virus spread in the canine population.

Owners should be instructed to keep dogs away from dog parks, shows, or other large gatherings, especially during active CIV outbreaks, because of the increased transmission risk in these environments.32

Shared equipment capable of transmitting the virus to other dogs should be disinfected with an agent specifically labeled to kill influenza A (eg, household bleach 1:30 dilution, quaternary ammonium compounds).

Future considerations

The introduction of the H3N2 virus and H3N8 virus are likely the first of many influenza A virus introductions into the canine population based on multiple examples of other subtypes seen in dogs in other areas.

Prompt isolation, diagnosis, treatment, and widespread vaccination (with relevant influenza strain[s]) are critical to prevent future widespread outbreaks.

ALI = acute lung injury, ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome, CIV = canine influenza virus, PCR = polymerase chain reaction