Canine Distemper Virus

Melissa A. Kennedy, DVM, PhD, DACVM, University of Tennessee

Somporn Techangamsuwan, DVM, MS, PhD, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand

Profile

Definition

Canine distemper virus (CDV) is a morbillivirus in the Paramyxoviridae family.

The causal viruses of rinderpest and measles are also included in this family.

CDV is an enveloped virus.

CDV is relatively easy to inactivate and requires only the removal of the lipid outer membrane.

Any disinfectant with detergent activity effectively inactivates this virus.

CDV, an RNA virus, has a significant mutation rate that is much greater than that of DNA viruses.

Domestic dogs are considered the reservoir species.

CDV also affects multiple wildlife species (eg, raccoons, skunks, foxes, ferrets) and can infect and cause disease in large felids (eg, lions).

Antigenic drift and strain diversity have been increasingly associated with outbreaks in wild species, domestic dogs, and exotic animals in zoos and parks.

New strains can emerge, so monitoring is necessary to ensure current vaccines are fully protective against predominant circulating strains.

A CDV-infected dog with purulent nasal discharge

Systems

The infection is associated with all lymphatic tissue.

Respiratory, GI, and urogenital epithelium; CNS; and optic nerves are also infected.

Incidence & Prevalence

The virus occurs globally, but it is a rare disease in typical pet populations.

Disease can be common in areas of low vaccine coverage.

Related Article: Infectious Respiratory Disease in a Dog

Geographic Distribution

The H-gene of CDV exhibits the highest variability within the genome.

Based on H-gene alignment, CDV is classified into 11 lineages: Asia-1, Asia-2, Asia-3, Asia-4, Europe, European wildlife, vaccine (America-1), America-2, South America, South Africa, and Arctic-like.

Signalment

The disease has been reported in dogs, bears, raccoons, ferrets, civets, red pandas, elephants, and large or exotic cats.

There is no breed or sex predilection.

Animals <6 months are particularly vulnerable.

Pathogenesis

The main route of infection is via aerosol droplet secretions from the oral or nasal cavities of infected animals.

Can also spread by direct contact.

The virus initially replicates in the epithelia and lymphoid ssue of the upper respiratory tract.

Depending on the level of immunity, CDV may spread via the bloodstream in an infected host, replicating in mononuclear WBCs.

The virus may then target epithelia of the respiratory system as well as the CNS.

In cases where CNS invasion occurs, neurons will become infected.

The degree of viremia and the extent of viral spread to other tissue are moderated by the level of specific humoral immunity in the host during the viremic period.

Related Article: Canine Idiopathic Inflammatory CNS Disease

Signs

Signs most often involve the respiratory tract.

GI signs may also occur.

Affected dogs are listless and have a decreased appetite.

In milder cases, signs may be similar to other agents of canine infectious respiratory disease complex.

Subclinical infection with shedding may also occur, depending on the level of host immunity.

Systemic signs are most common in unvaccinated dogs (eg, puppies) as maternal immunity wanes.

Conjunctivitis, nasal discharge, cough, and fever are classic signs.

Respiratory infection may involve the lower respiratory tract with possible primary viral pneumonia.

Secondary bacterial infection may occur.

Vomiting and diarrhea may be present.

Neurologic signs may be concurrent with epithelial signs (ie, respiratory disease, conjunctivitis, vomiting, diarrhea) with encephalitis caused by direct viral replication.

Alternately, neurologic disease may occur several weeks after resolution of epithelial invasion.

A significant amount of pathology results from virus immune response, as well as the virus itself.

Seizures and myoclonus are two of the more common signs.

The latter may affect limbs or manifest as chewing motion of the jaw.

Ocular disease may also occur.

Lesions include anterior uveitis, optic neuritis, and retinal detachment.

Infection during pregnancy may lead to abortion or stillbirth.

Puppies infected before permanent dentition may have enamel hypoplasia.

Digital hyperkeratosis may be noted.

Pitfalls

CDV should not be ruled out simply because there is no history of contact with other dogs.

Wildlife (eg, raccoons, foxes) can be an important source of CDV.

Although current vaccines appear to be protective against most circulating strains, vaccine breaks may occur.

PCR can detect virus from the vaccine for a few weeks postvaccination.

It is important to know if the dog has recently been vaccinated when testing samples for CDV.

The testing laboratory can help discern whether a positive result is from natural infection or vaccine.

Canine distemper virus, including the canine distemper vaccinal virus, kills ferrets. It is critical never to use the canine vaccine in this species.

Use vaccines licensed for use in ferrets only.

Diagnosis

Definitive Diagnosis

Diagnosis is established via virus identification in a clinical sample through use of reverse-transcriptase PCR of whole blood, a swab of conjunctiva or tissue, CSF, or urine.

Urine is a good choice for PCR testing in patients with CDV encephalitis after resolution of epithelial signs.

CDV may be detected in urine for a longer period than other sample types.1

CDV detection in urine and CSF was equivalent in one study of neurologic cases.1

Postmortem evaluation and microscopic findings confirm infection.

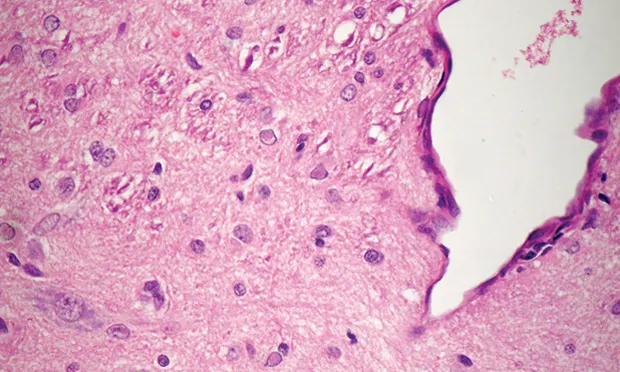

The specific lesion of CDV is eosinophilic intranuclear/intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies in glial cells, neurons, epithelial respiratory cells, and cells of the GI and urogenital tracts (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1 Eosinophilic intranuclear inclusion bodies in glial cells in the cerebrum of a dog infected with CDV

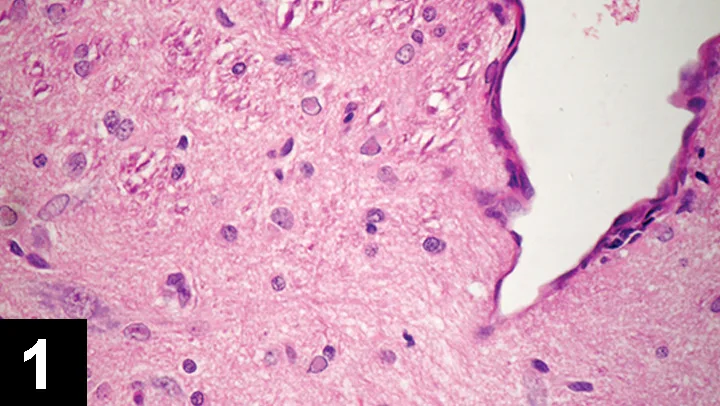

Virus isolation is the gold standard for diagnosis and is useful in low levels of viral infection through observation of typical syncytial cell formation (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2 Typical cytopathic effect of CDV isolation shows numerous small and large syncytium cell formations

Immunocytology can be used to enhance the visibility of inclusion bodies by fluorescein-conjugated CDV antibodies.

Fluorescent color confirms distemper infection, but the lack of color does not rule it out.

Differential Diagnosis

Distemper is sometimes confused with other systemic infections (eg, leptospirosis, canine infectious hepatitis, rabies, canine infectious respiratory disease complex, Rocky Mountain spotted fever).

Laboratory Findings

Clinical findings may include lymphopenia.

Inclusions in WBCs and RBCs may be noted, especially in early infection.

Analysis of a CSF specimen in dogs with neurologic disease shows increased protein and WBCs—primarily lymphocytes.

Serologic studies can be helpful in unvaccinated dogs, particularly if IgM is detected.

In dogs with unknown history or in vaccinated animals, the usefulness of serology is dubious.

Measuring CDV-specific IgM can be useful if the vaccination history is known.

If the dog has not been vaccinated in the past 1–2 months, IgM should be negative unless exposed to infection with a field strain.

Detection of antibodies in CSF is significant if the blood–brain barrier is intact.

This does not occur unless CNS invasion is present.

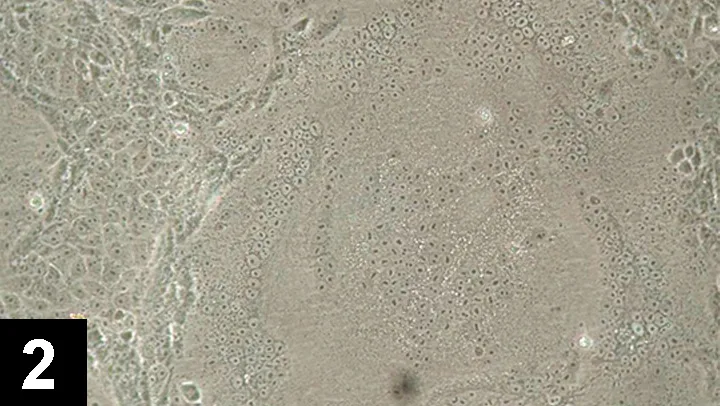

Immunohistochemistry using specific antibodies against CDV is helpful when typical lesions are not evident (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3 Diagnosis by immunohistochemistry using specific antibodies against CDV shows positive infected transitional epithelial cells (brown color)

Postmortem Findings

Thymic atrophy is a consistent finding in infected puppies.

Hyperkeratosis of the nose and footpads is often found in dogs with neurologic manifestations.

Bronchopneumonia, enteritis, and skin pustules may also be present, depending on the degree of secondary bacterial infection.

In cases of acute to peracute death, respiratory abnormalities may be found exclusively.

Histologically, CDV causes necrosis of lymphatic tissue; interstitial pneumonia with cytoplasmic and intranuclear inclusion bodies in respiratory, urinary, and GI epithelium; and neurologic complications.

Neurologic complications include: neuronal degeneration, gliosis, noninflammatory demyelination, perivascular cuffing, nonsuppurative leptomeningitis, intranuclear inclusion bodies (mainly in glial cells; Figure 1).

Treatment

Inpatient or Outpatient

Treatment depends on severity of clinical signs.

If mild respiratory distress occurs, animals may be treated as outpatients with supportive care (ie, nebulization, antibiotics for secondary infections, mucolytics, cough suppressants).

If signs are more severe, dogs may require hospitalization and should be housed in isolation.

If neurologic disturbances are present (eg, tetraplegia, semicoma, seizure), euthanasia should be considered.

Medications

Drugs & Fluids

Treatment is supportive only.

Antiviral medications are not routinely used.

No single treatment is specific or uniformly successful.

Secondary bacterial infection frequently results in bronchopneumonia, which requires broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy and expectorants or nebulization.

Parenteral therapy is required when GI signs or dehydration is present.

Fluids such as lactated Ringer’s solution may be supplemented with vitamin B and/or C to replace lost vitamins and to stimulate the appetite.

Water, food, and oral drugs should be discontinued if vomiting and diarrhea are present.

Parenteral antiemetics may be required.

In dogs with status epilepticus, diazepam should be administered IV or PR, followed by phenobarbital for maintenance prevention.

Follow-Up

Patient Monitoring

Infected dogs with systemic signs (eg, vomiting, diarrhea) should undergo extensive daily monitoring.

Disinfection of the environment (eg, shelter, house, kennel) is recommended.

CDV is extremely susceptible to common disinfectants.

In General

Relative Cost

Diagnostics: $–$$

Treatment and follow-up care: $$–$$$

Cost Key

$ = <$100

$$ = $100-$250

$$$ = $250-$500

$$$$ = $500-$1,000

$$$$$ = >$1,000

(Actual costs will have regional variations)

Prognosis

Prognosis is guarded.

Prevention

Control is accomplished through vaccination.

Current vaccines include strains of the American lineage (Onderstepoort or Lederle strains).

After recovery from natural infection or following booster vaccination, immunity can persist for years.

Vaccination for CDV can begin as early as 6–8 weeks of age, with boosters every 2–4 weeks until at least 16 weeks of age. For naïve puppies or adults vaccinated after maternal immunity has waned (approximately 16 weeks of age) a single live or recombinant vaccine should be sufficient to induce protection.

In older vaccinated dogs, an annual or triennial distemper booster is recommended, depending on the risk for infection.

Client education about purchasing puppies from crowded pet markets is important.

CDV is susceptible to ultraviolet light, heat, drying, and all routinely used disinfectants.

No vaccine is 100% effective, but regular vaccination can help protect animals.