In the Literature

Turicea B, Sahoo DK, Allbaugh RA, Stinman CC, Kubai MA. Novel treatment of infectious keratitis in canine corneas using ultraviolet C (UV-C) light. Vet Ophthalmol. 2024. doi:10.1111/vop.13265

The Research …

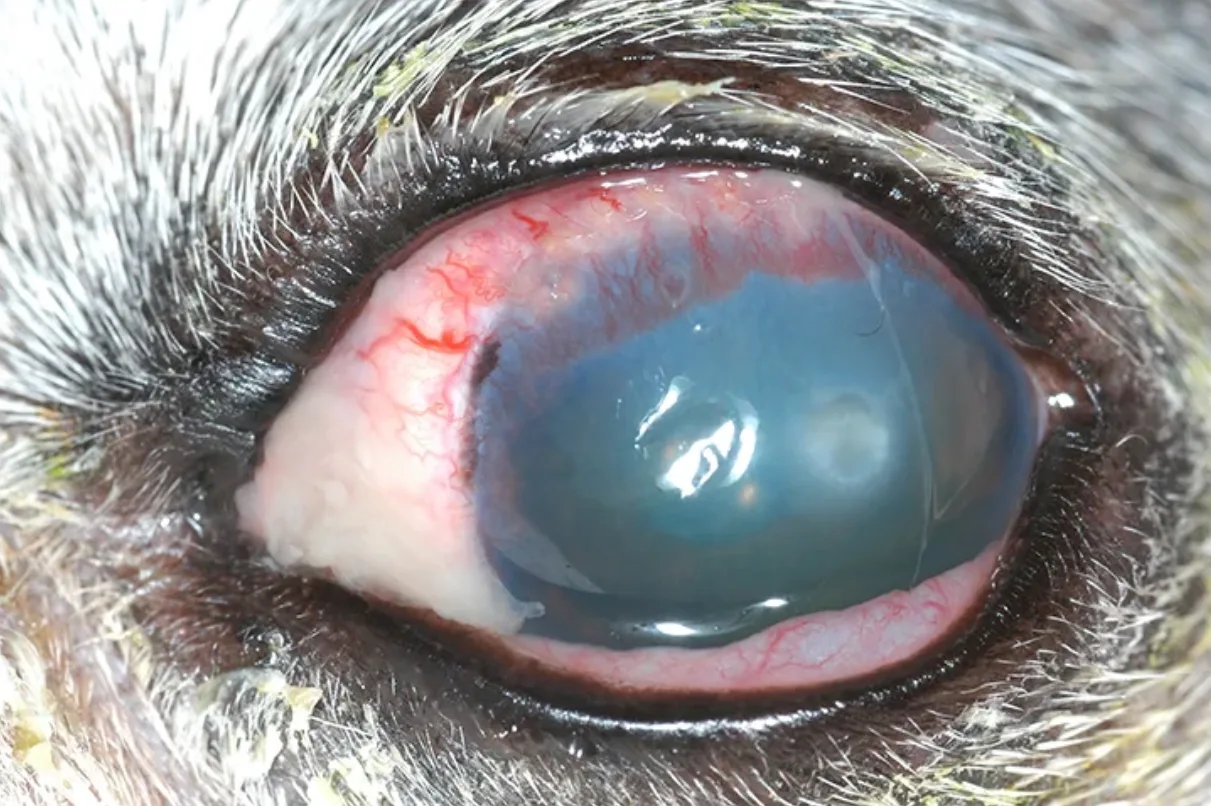

Infectious keratitis is common in veterinary medicine and can cause significant morbidity, pain, loss of ocular function, and pet owner expense (Figure). Aggressive and frequent antimicrobial therapy is required and often based on empirical data at presentation. Corneal culture and susceptibility testing should ideally be performed to determine the best antimicrobial choice, but waiting for culture results may jeopardize ocular function. Ultraviolet C (UV-C) light can have a germicidal effect on bacteria, fungi, and protozoa that affect the ocular surface,1,2 as absorption of UV-C light leads to formation of lethal photoproducts and production of free radicals that damage microbial DNA.3

Infectious keratitis in a dog with evidence of corneal edema, malacia, corneal defect, and hypopyon

This study evaluated UV-C light therapy for treatment of canine bacterial keratitis. Researchers first determined an in vitro minimum dose needed to inhibit bacterial growth using a commercially available, handheld UV-C light-producing device. Bacterial cultures, including Staphylococcus pseudintermedius, Streptococcus canis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, were exposed to a single dose of UV-C light for 5, 15, or 30 seconds. Plates treated with UV-C light exhibited 100% bacterial inhibition where the beam was applied, with results indicating that UV-C light at a distance of 10 mm for 15 seconds was required for 100% inhibition. Shorter-duration exposures did not achieve the desired bactericidal effect, and pathogen regrowth occurred.

Testing was then performed on donor canine corneal buttons free of ocular disease. Superficial corneal ulcers were created, and single-strain and polymicrobial samples were introduced onto the ulcers and into the midcorneal stroma. The buttons were treated with UV-C light at a distance of 10 mm for 15 seconds. Ulcers had a significant decrease in bacterial count after treatment, but midstromal results were inconclusive. Variability in treatment effectiveness may have been due to stromal-depth inoculation challenges, poor UV-C light penetration into deeper tissues, corneal edema, and/or UV-C light scattering.

… The Takeaways

Key pearls to put into practice:

Early and aggressive treatment of infectious keratitis is warranted. A study found gram-positive isolates were responsible for 71% of bacterial keratitis cases in dogs and gram-negative isolates were responsible for 29% of cases.4 Gram-positive bacteria are typically more resistant to UV light than gram-negative bacteria due to a thick peptidoglycan layer.5,6 In addition, tear film and corneal epithelium can absorb 50% to 75% of UV-C radiation1,7; corneal ulcers with severe corneal edema may therefore not be suitable for this therapy.

Additional study of clinical safety is needed before light therapy techniques are used in companion animals. UV light may induce neoplasia and cause lens and retinal damage, and high, frequent doses (particularly of UV-B light) are carcinogenic.1,8,9 UV-C light does not cause corneal damage at high doses when low wavelengths (220-235 nm) are used, and corneal epithelial damage is minimal when large doses are used at an increased wavelength.7,10 Newer light therapy approaches use argon cold atmospheric plasma.

You are reading 2-Minute Takeaways, a research summary resource presented by Clinician’s Brief. Clinician’s Brief does not conduct primary research.