Body Cavity Effusions: Two Case Studies

Proper classification of body cavity effusions is based on conclusions drawn from color and clarity of fluid, total protein concentration, cell quantity, and microscopic evaluation.

Case StudiesThese cases demonstrate how additional information can be gleaned through cytologic analysis and classification of body cavity effusion (See Steps to Classifying Body Cavity Effusions).

Case 1: Labored BreathingA 3-year-old castrated collie was presented for labored breathing, shortness of breath, and collapse. Physical examination revealed muffled heart and lung sounds with synchronous peripheral pulses. Thoracic radiographs revealed moderate pleural effusion.

Ask Yourself...

1. Based on the fluid parameters given, what is the classification of this fluid?2. What are some differentials for this particular fluid type in the thoracic cavity?

Figure 1. Gross image of pleural fluid. The fluid is pink and opaque.

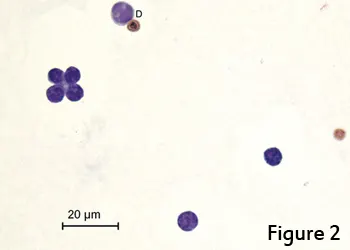

Cytology InterpretationThe fluid was pink, opaque, and comprised predominantly of small, well-differentiated lymphocytes, which raised concern for a chylous effusion. The fluid’s triglyceride concentration was >100 mg/dL, making diagnosis of chylous effusion possible without concurrent serum triglyceride measurement.1 If the fluid triglyceride concentration is <100 mg/dL, a fluid triglyceride concentration >2× the serum triglyceride concentration is also considered diagnostic. Total protein by refractometer was likely falsely increased by the lipid content of the fluid sample. Given the presence of a chylous effusion, differentials included lymphangiectasia, cardiac disease, heartworm disease, idiopathic chylothorax, fungal granuloma, lung lobe torsion, diaphragmatic hernia, neoplasia, and venous thrombi; less likely, congenital abnormality; rarely, thoracic duct rupture.

Figure 2. Small, well-differentiated lymphocytes in a proteinaceous background; thoracic fluid from a dog. One of the lymphocytes is larger with smudged chromatin, a sign of partial degradation (D). (Wright-Giemsa, 50×)

Chest radiographs were repeated after thoracentesis; no cardiac abnormalities, masses, or lung lobe torsion were observed. Additional tests, including echocardiogram and SNAP 4Dx, were within normal limits. The chylous effusion was deemed idiopathic, and the patient has been successfully treated for 2 years with rutin and therapeutic thoracentesis as needed.

Did You Answer...1. Chylous effusion2. Lymphangiectasia, cardiac disease, heartworm disease, idiopathic chylothorax, fungal granuloma, lung lobe torsion, diaphragmatic hernia, neoplasia, venous thrombi; less likely, congenital abnormality; or rarely, thoracic duct rupture

Case 2: Lethargy & Inappetence

A 4-year-old intact female beagle was presented for lethargy and inappetence of 5 days’ duration. She was febrile (103.1°F) and painful on palpation of her midabdomen. CBC revealed a normal leukocyte count with regenerative left shift and 2+ toxicity in some neutrophils. Abdominal ultrasonography demonstrated moderate free abdominal fluid.

Ask Yourself...

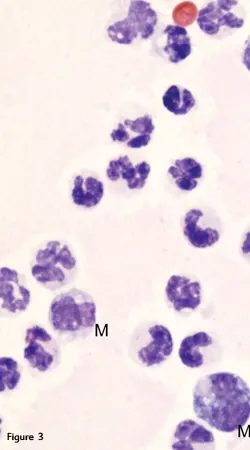

1. What is the predominant cell type (Figure 3)?2. What is the estimated total nucleated cell count if this image represents an average field at 100× (Figure 3)?3. Any abnormalities noted with the predominant cell type (Figure 4)?

Figure 3. Mature, mildly karyolytic neutro__phils and 2 mononuclear phagocytes (M); abdominal fluid from a dog. (Wright-Giemsa, 100×)

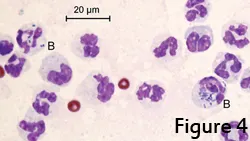

Cytology InterpretationThe abdominal fluid is best classified as an exudate based on its total protein concentration, nucleated cell count, and predominant nucleated cell type. Further examination revealed degenerative changes in many neutrophils, including karyolysis and karyorrhexis. The neutrophils contained intracellular bacteria, which allowed further classification as a septic exudate. Aerobic culture of the fluid yielded scant to moderate growth of Escherichia coli and Enterococcus spp. During exploratory laparotomy, a 15-inch cloth was found in an area of devitalized jejunum with a small perforation. Resection and anastomosis were performed to remove the affected intestinal segment and the animal was placed on IV broad-spectrum antibiotics. The patient recovered uneventfully.

Figure 4. Mature neutrophils with fewer bands exhibiting karyolysis and containing intracellular coccobacilli and bacilli (B); abdominal fluid from a dog. (Wright-Giemsa, 100×)

**

Did You Answer...**1. Mature neutrophils2. 19 complete cells/field × (100 objective)2 = 190,000/µL; machine count was 184,600/µL3. Mature neutrophils with fewer bands exhibiting karyolysis and containing intracellular coccobacilli and bacilli, indicative of bacterial infection

SARAH S. K. BEATTY, DVM, is a clinical pathology resident at University of Florida College of Veterinary Medicine. Her interests include oncology, ruminant medicine, and wildlife and exotics. As a veterinary student, Dr. Beatty served as the NAVC OnCampus student representative for University of Florida, where she earned her DVM.

Related ArticlesEffusion in CatsThoracocentesis

BODY CAVITY EFFUSIONS • Sarah S. K. Beatty & Heather L. Wamsley

References

1. Lipoprotein electrophoresis differentiation of chylous and nonchylous pleural effusions in dogs and cats and its correlation with pleural effusion triglyceride concentration. Waddle JR, Giger U. Vet Clin Pathol 19:80-85, 1990.2. Laboratory technology for veterinary medicine. Lassen ED, Weiser G. In Thrall MA, Weiser G, Allison R, Campbell TW (eds): Veterinary Hematology and Clinical Chemistry—Ames, IA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012, pp 7-9.

Suggested Reading

Abdominal, thoracic, and pericardial effusions. Alleman AR. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 33:89-118, 2003.Body cavity fluids. Rebar AH, Thompson CA. In Raskin RE, Meyer D (eds): Canine and Feline Cytology, 2nd ed —St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier, 2010, pp 171-191.Effusions: Abdominal, thoracic, and pericardial. Rizzi TE, Cowell RL, Tyler RD, Meinkoth JH. In Cowell RL, Tyler RD, Meinkoth JH, DeNicola DB (eds): Diagnostic Cytology and Hematology of the Dog and Cat, 3rd ed —St. Louis: Mosby Elsevier, 2008, pp 235-255.