Bandaging Complications

Tisha A. Harper, DVM, DACVS, University of Illinois

What are common complications associated with external coaptation, and how can their occurrence be minimized?

External coaptation refers to the use of casts, splints, bandages, hobbles, orthotics, or slings to help stabilize fractures or luxations, to reduce postoperative swelling, or to help manage and protect wounds.1,2

Careful attention to the suitability and application of external coaptation is important; inappropriate application and/or case selection can lead to unsatisfactory results.2 (For application tips, see General Guidelines for Applying External Coaptation.) Adequate monitoring of the bandage by the clinician and the pet owner can help to minimize complications—or at least identify and address problems before major issues occur.

General Guidelines for Applying External Coaptation

Patient selection is important.3

For example, immature patients with simple fractures are better suited for fracture stabilization using a cast, as they heal quickly and will need only a short period of limb immobilization.3 However, fractures of the distal radius and ulna in miniature and toy breeds, regardless of age, are not good cases for external coaptation, as this often results in delayed union or nonunion.4,5 Rigid stabilization is required for management of these fractures.4,5

External coaptation is also challenging in chondrodystrophic breeds, well-muscled dogs, and obese patients, as it is difficult to conform and maintain the cast, splint, or bandage, particularly on the upper limb.2,3 Extra care should be taken in sighthounds, which are more likely to develop cast-associated soft tissue injuries as compared with other breeds.6

External coaptation is most easily applied over short hair.

This minimizes the chances of slipping and concealment. The hair should be trimmed or clipped in long-haired breeds.

Sedation or anesthesia is recommended for application of bandages and casts.

Completed casts and bandages should have a smooth appearance.

Moderate pressure should be used when applying casting tape, which should overlap the preceding wrap by 50%.7 Wrinkles and bulges can become pressure points that can lead to the development of sores. When drying, the palm of the hand should be used to support a cast to avoid indentations created by the fingers.2,8,9

Placing donuts over bony prominences should be considered.3

When using donuts, ensure that they are appropriately wrapped and not mobile within the bandage, as this can lead to abrasions.

Even application of full-length cast-padding, particularly under casts, is recommended to decrease pressure on the skin.10

Stirrups should be applied before placing certain bandages to minimize slipping.

Note, however, that stirrups will not help with an improperly applied bandage.2 One author recommends placing stirrups on the dorsal and palmar/plantar aspects of the distal limb unless precluded by a wound or incision. This avoids applying medial-lateral pressure with the stirrups, which can lead to sores as a result of one toe nail digging into an adjacent toe or of the cast or bandage rubbing on the toes during weight bearing.2

Apply coaptation with the limb at a functional angle is best achieved using an assistant who keeps the limb in the appropriate position throughout the process.

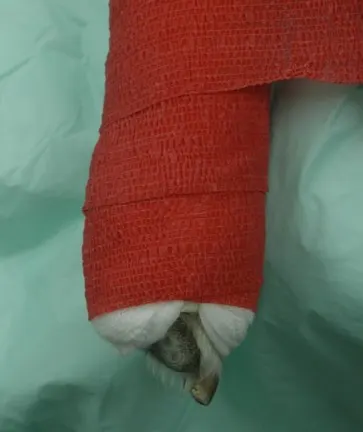

Bandages should not completely cover the toes (with few exceptions).

The nails and pads of digits 3 and 4 should be visible to assess for swelling and hypothermia. Initial bandage injuries will likely manifest in the first 24-48 hours of bandage application; therefore, bandages should be reassessed 24 hours after application.11 This is important, as many bandages in veterinary medicine are applied under sedation or anesthesia—particularly casts in cases that are considered at high risk for developing complications.6

If there are any issues associated with a bandage, cast, splint, it should be removed, the limb evaluated, and the coaptation replaced.2

In some cases, an alternative method of stabilization may need to be considered.

Extra care should be taken when applying external coaptation in high-risk patients (eg, obtunded or comatose polytrauma patient, patients under general anesthesia, patients with altered peripheral sensation), as they are unable to communicate/indicate an immediate problem with the bandage.12

Common Bandaging Problems & Complications

Bandage Too Tight

A bandage that is too tight can lead to pressure sores and irritation, which can cause the patient to chew at the bandage (Figure 1).8 Tight bandages can also result in vascular compromise, which can lead to local hypothermia and swelling of the limb and toes due to venous stasis; if left unattended, this can also result in necrosis (Figure 2).11 Tight bandages can also compress peripheral nerves and cause temporary or permanent limb dysfunction.9,11

Figure 1A Cast chewed off over the hock due to irritation.

Bandage Too Loose

A loose bandage might fall off the limb or slide up and down the limb, which can cause friction leading to excoriation and abrasions.8,9,12 It can also slip down to the most distal aspect of the limb, where it can constrict the limb and cause swelling just proximal to the slipped bandage.

Cast application should be done after swelling in the limb has subsided (typically after 24-48 hours). A splinted bandage or a Robert Jones bandage can provide support in the interim.2,8

The pressure under a bandage is proportional to the tension on the bandage material during application.11 Also, higher pressure develops over an area of the limb with a smaller circumference that is immediately proximal to an area with a larger circumference (eg, immediately proximal to the carpus or tarsus).11

To avoid bandages that are too tight or loose, proper bandage tension is important.11 Tension should only be applied on one surface of the limb when applying cast padding or roll gauze. Tension should not be applied when applying casting tape.13 Unrolling casting tape during application can help minimize excessive tension.12

Pressure Sores

Pressure sores can occur with bandages that are applied too tight; however, even with appropriately applied coaptation, pressure sores can occur. Bony prominences (eg, olecranon, calcaneus, accessory carpal pad) need special attention when incorporated into any form of external coaptation (Figure 3).11

Figure 3 Pressure sore over the elbow following application of a caudal splint

To minimize the occurrence of pressure sores, the clinician may opt to use donuts—made out of folded cast padding, rolled stockinette, or sponge (Figure 4).3 The hole is centered over the prominence to be protected; this way, force from the bandage or cast is distributed over a larger area (the ring of the donut) instead of the smaller area of the prominence.

Folds and uneven bandages (ie, with lumps, bumps, or creases) can lead to focal areas of increased pressure and cause pressure sores. It is therefore important that bandages are smooth and applied with even pressure.<sup9 sup> This is particularly important when casts are applied. Creating indentations in the cast during application should be avoided by supporting the cast with the palm of the hand rather than the fingers.2,8,9,11

Bandage Not of Appropriate Length or Coverage

The bandage ending at the metacarpophalangeal joint or metatarsophalangeal joint is probably one of the most common causes of swelling and necrosis, in the author’s experience. Bandages that end at the metacarpo- or metatarsophalangeal joint or proximal interphalangeal joint can constrict the digits, which can lead to hypothermia (Figure 5) and swelling of the toes (Figure 6).2

Figure 5 Distal aspect of a modified Robert Jones bandage with the pads and nails of P3 and P4 exposed to assess for swelling, cyanosis, and hypothermia

Only the pads and nails of digits 3 and 4 need to be exposed to assess for swelling or hypothermia.2,8

With any bandage that leaves the toes exposed (eg, modified Robert Jones, Robert Jones, Ehmer sling, carpal sling, spica splint), the bandage must allow for toe evaluation without compromising distal limb circulation. Bandages that do not extend proximally enough may not provide sufficient support (eg, casting for a fracture).2,8 Bandages, particularly splints, that extend too far beyond the toes can also be problematic and can cause the splint to shift proximal/distal on the limbs.

Loss of Joint Mobility & Range of Motion

Loss of joint mobility and range of motion can occur because of infrequent bandage changes, prolonged immobilization, and lack of range-of-motion exercises during bandage changes. It can eventually lead to disuse atrophy and fracture disease. Mild cartilage degeneration can be seen following 4 weeks of stifle immobilization.14 This may be seen in patients with non–weight-bearing slings (eg, Ehmer sling, carpal sling). It can also be seen secondary to cast application, particularly in immature patients.9,14,15

Bandage change frequency can vary and depends on bandage type and purpose. For example, a cast may need to be changed every 2 weeks in young, rapidly growing pets; however, a cast can be maintained for as long as 4 weeks in an adult animal.13 If circumstances allow, a sling should be removed daily to facilitate passive range-of-motion exercises and then reapplied.16 At minimum, this should be done weekly. A rule of thumb is that a bandage should be changed any time there is patient discomfort or suspicion of ischemic injury.

Abrasions

As with bandages that are too tight or too loose, abrasions can occur if there is insufficient padding, particularly with casts and splints.9,10 Too little padding can also lead to complications (eg, skin excoriations, pressure ulcers over prominences that are not appropriately protected).9

Too much padding is likewise not ideal, as this will prevent adequate stabilization. If there is too much padding under a cast, the leg can slide inside the cast and this can cause abrasions. The use of too much padding can also allow cast padding to slide down the leg. As a result, some areas under the cast may have no padding and other areas may have none—both of which can lead to abrasions and sores.2,8,10

Two layers of evenly applied cast padding are generally recommended under a cast, with the cast padding wrapped such that it overlaps the previous layer by one-third to one-half.2,7 Special attention should be paid to the proximal and distal aspects of casts and splints, as extra padding is often needed to ensure they do not rub against the skin.2,12,17 Regular evaluation of the skin in patients with slings is also important, as the material used to make the sling can rub against the skin (eg, inner aspect of the thigh with an Ehmer sling).

Bandage Is Wet

A bandage can be wet because of external moisture (eg, rain) or because of serum production from a wound or ulcer under the bandage. Moist dermatitis, skin maceration, and ulceration can develop because of wet bandages.9 Odor due to serum production by the wound may be the first sign that an ulcer is developing beneath a bandage or cast, where the moist, warm environment is ideal for bacterial growth.9

A wet bandage should be removed, and it should be replaced if continued support and/or protection is needed. When pets are taken outdoors, bandages should be kept clean and dry with a covering of a thick plastic bag or commercial bandage.

Client Education

Pet owners play an important role in minimizing bandage complications.8,9 Although owner observation is important, the onus should not be placed solely on owners to identify a problem.

Written guidelines for at-home bandage care (see Client Handout: At-Home Bandage Care) should be provided and should stress the importance of maintaining an Elizabethan collar on the pet and keeping the bandage dry. Pet owners should also be instructed to look for signs that might indicate a problem with the coaptation. Such signs may include drainage; foul odor; spreading or cyanosis of toenails; cold digital pads; and discomfort, which can manifest as the pet licking or clawing the bandage.2,8,18

Owners should commit to bandage changes as scheduled and should be instructed to seek immediate veterinary care if there is structural damage to the coaptation device or if any of the above signs are noted.8 If there are signs of pain or excessive licking or chewing at the bandage, the bandage should be removed and the entire limb and any other affected area evaluated.11

Lameness, malodor, digital swelling, and/or edema may not be reliable indicators of bandage problems.6 Similar difficulties seem to occur in human pediatric patients when complications from wet cast padding are not noticed until final cast removal.9

Client Handout: At-Home Bandage Care

The bandage must be kept clean and dry at all times. Place a plastic bag over the bandage when your pet is outdoors.

Monitor the limb twice daily for signs of swelling and infection (eg, discomfort, drainage, abnormal odors, spreading of the toenails) and inspect the top and bottom of the bandage for evidence of skin abrasions.

Commit to scheduled bandage checks and changes; however, seek immediate veterinary assistance if the bandage loosens, is structurally damaged, or if your pet is obsessively licking or chewing at the bandage.

Your pet must wear an Elizabethan collar at all times until the bandage is removed.

No running, jumping, playing, or off-leash activities are allowed for your pet while it has a bandage. Only leash walks are allowed.