Atypical Transitional Epithelial Cells

Evaluation of urine sediment is useful when confirming a normal urine sample or diagnosing inflammation, infection, crystalluria, or neoplasia. Some sediment findings have multiple potential causes and must be considered in context of sample collection method, presenting complaint, physical examination findings, imaging, and results of other laboratory and diagnostic results.

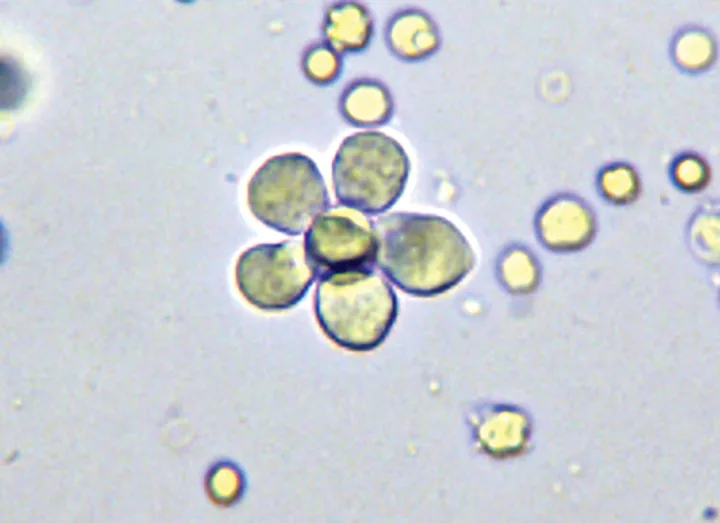

Unstained urine sediment wet mount, original magnification 200×. An unusual flower-shaped aggregate of transitional epithelial cells is shown.

Transitional epithelial cells line the urinary tract from the renal pelvis to the proximal urethra and are typically seen in low numbers in urine sediments. In many cases, large numbers or aggregates of transitional epithelial cells in wet-mount urine sediment preparations should prompt additional investigation (Figure 1).

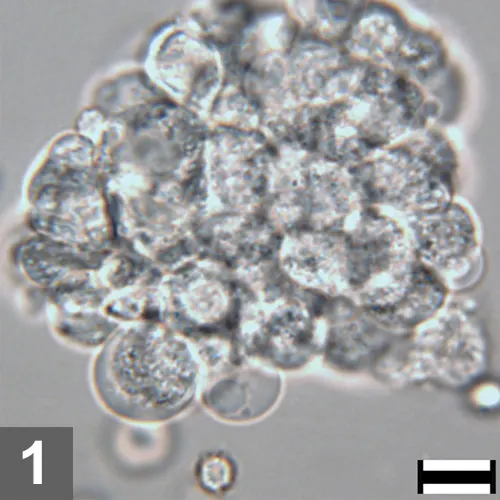

Figure 1. Unstained urine wet mount, 500× magnification, bar = 10 µm. A large, dense aggregate of epithelial cells is pictured. Observation of a large number of epithelial cells, especially in aggregates or sheets in urine, is abnormal. To better evaluate cell morphology and identify features of atypia, a dry mount cytologic preparation is very helpful.

Atypical epithelial cells may have larger-than-normal nuclei, coarsely clumped chromatin, large and prominent nucleoli, variable size and shape of nuclei and cells, multiple nuclei per cell, increased mitosis, and other features. Cellular atypia is not only seen with neoplasia but can also be seen with hyperplasia associated with inflammation, infection, or in response to mechanical trauma.

When atypical epithelial cells are observed in a urine sediment wet-mount preparation, it is helpful in many cases to prepare a dry-mount urine cytologic specimen for further evaluation, as thorough assessment of cell morphology is often not possible using low magnification and a wet-mount preparation. A dry-mount urine sediment cytologic specimen can also be easily shipped to a commercial laboratory for evaluation by a pathologist as needed.

In the following cases, atypical transitional epithelial cells or aggregates of epithelial cells were identified in the wet-mount urine sediment preparation, and additional cytologic preparations were pursued. In two of the cases, urine sediment dry-mount preparations were made. For the other two cases, additional techniques were used to collect a representative sample.

Related Article: Interventional Radiology: A Trend in Veterinary Medicine

Examination of exfoliative cytology obtained by urinary catheterization or fine-needle aspirate are relatively noninvasive and inexpensive methods for obtaining specimens from the urethra or urinary bladder mucosa.1-3 There is a low risk for seeding neoplastic cells into the peritoneum or body wall with fine-needle aspiration (FNA), but some recommend the use of urinary catheterization to avoid this complication,4 especially in patients with an operable bladder mass.

Case 1

A 5-year-old, spayed hound crossbreed was presented for a 1-year history of pollakiuria and intermittent inappropriate urination in the house. Urinalysis was conducted (Table, Urinalysis Physical and Chemical Results); radiographs disclosed urolithiasis.

Diagnosis

Urolithiasis with bacterial cystitis with transitional cell hyperplasia

Interpretation

This patient’s transitional epithelial cell atypia was associated with cystoliths and bacterial infection. The patient had hyperplasia of the bladder epithelium caused by underlying mechanical trauma from cystoliths and irritation caused by inflammation and infection associated with the cystoliths.

Related Article: Hematuria in a Dog

Several oval, radiopaque uroliths were identified on radiography; no urinary tract masses were visible on ultrasonography.

This case illustrates the importance of exercising caution and not over-interpreting cellular atypia in the presence of infection and inflammation, which induces reactive epithelial hyperplasia with cytologic changes that may mimic malignancy.

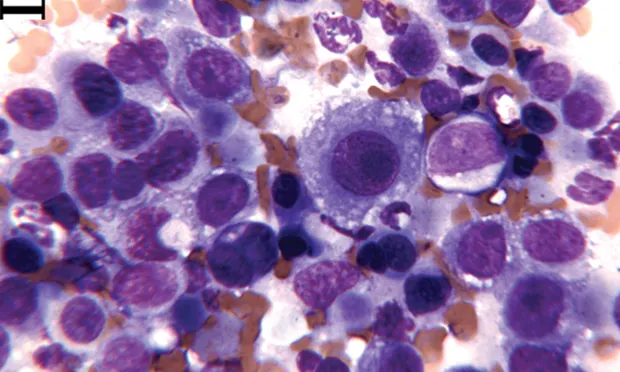

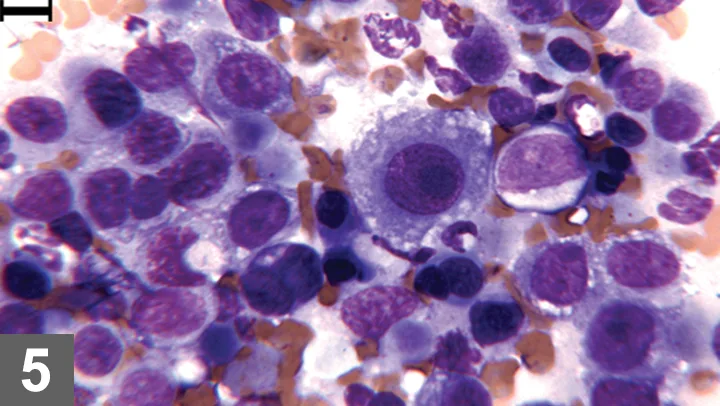

Wright-Giemsa–stained urine sediment, dry-mount, 1000× magnification. An aggregate of epithelial cells is present in the center. Multiple neutrophils are present above and below the epithelial cells. Extracellular bacilli are at the far left and right.

Case 2

A 12-year-old, spayed greyhound was presented for anorexia, vomiting, and stranguria. The patient was azotemic, and thickening of the bladder trigone area was identified by ultrasound. Urinalysis was pursued (Table, Urinalysis Physical and Chemical Results).

The transitional cells in the urine sediment dry-mount cytology were moderately to highly atypical; however, pyuria and bacteriuria were also present. This confounded diagnosis of neoplasia by urinalysis as infection can induce hyperplasia with cytologic changes that mimic malignancy.

Because urinalysis results were equivocal and a discrete bladder mass was not visualized, FNA of the bladder trigonal thickening was performed to further investigate potential transitional cell carcinoma versus the less likely consideration of hyperplasia secondary to the infection.

Diagnosis

Transitional cell carcinoma with secondary neutrophilic inflammation and bacterial infection

Interpretation

With the improved cytologic detail provided by the FNA, the atypical cellular features were more reliably assessed. Although infection was present, the cytodiagnosis of transitional cell carcinoma was made based on the consistently high degree of epithelial cell atypia in the aspiration sample.

Related Article: Prostate Cytology

The decision to perform FNA in this case was based on multiple factors, including the client’s wishes for palliative care, patient’s general health status, disease extent and location (bladder trigone), and overall prognosis. Because prognosis was unlikely to be affected by seeding along the needle tract, FNA was performed to provide additional diagnostic information in this case.

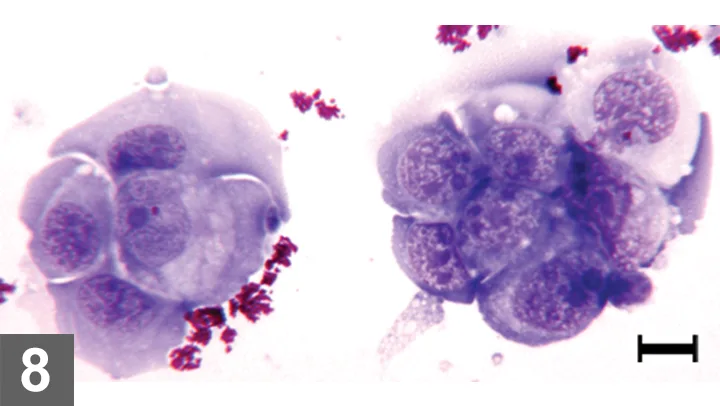

Wright-Giemsa–stained FNA of bladder thickening, 500× magnification, bar = 10 µm. Moderately to markedly atypical epithelial cells with mildly increased neutrophils. The neutrophil at the top center contains phagocytized bacilli.

Case 3

A 10-year-old, castrated Cairn terrier was presented for gross hematuria. Urinalysis confirmed hematuria and disclosed increased atypical epithelial cells (Table, Urinalysis Physical and Chemical Results)**. Imaging disclosed an apical bladder mass, which was further evaluated by exfoliative (traumatic) catheterization cytology.**

Diagnosis

Transitional cell carcinoma

Interpretation

Results of urinalysis showed no evidence of inflammation or infection that would induce reactive hyperplasia of the epithelial cells or explain the presence of atypical epithelial cells in the urine sediment. Coupled with the clinical presentation, this was consistent with transitional cell carcinoma.

Diagnostic imaging may aid in the diagnosis of transitional cell carcinoma in patients with atypical epithelial cells in the urine sediment and help exclude urolithiasis or document a urinary tract mass. Abdominal imaging of this patient disclosed an apical bladder mass. Given the mass location, this patient was considered a candidate for aggressive medical therapy and surgical removal. Preoperative evaluation included cytology of the mass.

Exfoliative catheterization was chosen in lieu of FNA to avoid seeding cancer cells along the needle tract (peritoneum, body wall, subcutaneous tissue). For this patient with an apical bladder mass, the cytologic finding of marked epithelial cell atypia without infection, inflammation, or cystic calculi was diagnostic for transitional cell carcinoma. The diagnosis was confirmed histopathologically.

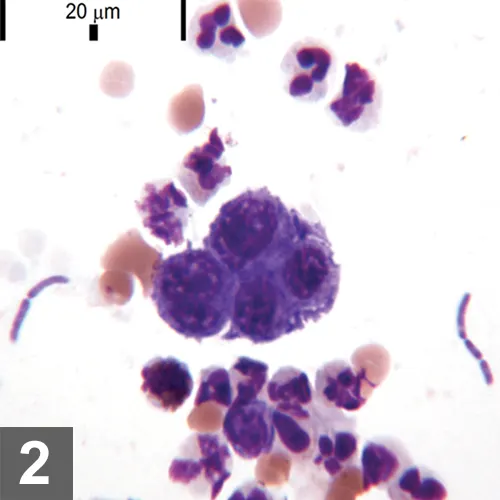

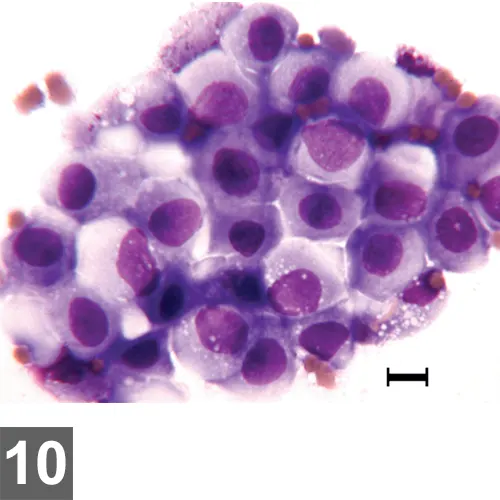

Wright-Giemsa–stained urine sediment, dry-mount, 500× magnification, bar = 10 µm. Aggregates of markedly atypical epithelial cells with multiple features of malignancy are shown. The granular magenta material is lubricant used with catheterization. This artifact may obscure cytologic detail in some cases.

Case 4

A 4-year-old, castrated domestic shorthaired cat was presented for anorexia, anuria, and apparent abdominal pain. On bladder palpation, the patient voided urine and resisted additional palpation. Following appropriate analgesic administration, cystocentesis was performed and urinalysis results were available (Table, Urinalysis Physical and Chemical Results).

Diagnosis

Feline lower urinary tract disease (FLUTD) with transitional epithelial cell hyperplasia

Interpretation

The mild epithelial cell atypia represents reactive hyperplasia associated with idiopathic cystitis and FLUTD. Culture and imaging did not show underlying infection or anatomic abnormality, although abundant hyperechoic material consistent with marked crystalluria was present.

It is unusual to observe large sheets of epithelial cells in urine sediment. Dry-mount cytology permits thorough evaluation of cytomorphology and optimally preserves cells for evaluation by a pathologist at a reference laboratory.

Wright-Giemsa–stained urine sediment dry-mount, 500× magnification, bar = 10 µm. Mildly atypical epithelial cells in sheets are pictured associated with numerous erythrocytes.

Table > Urinalysis Physical and Chemical Results

Values with asterisk (*) are outside reference interval or value

| WBC/HPF | TNTC* | 20–25* | 0–2 | 3–5* | 0-3 | | RBC/HPF | TNTC* | 20–25* | 5–10* | 50–100* | 0–5 | | Bacteria/HPF | Many bacilli* | Occasional bacilli* | None | None | Depends on collection method | | Crystals | Occasionally amorphous | None | None | Many struvite* | Depends on crystal type |

HPF = high-power field (40× magnification), LPF = low-power field (<10x magnification is LPF), TNTC = too numerous to count, WBC = white blood cell, RBC = red blood cell, USG = urine-specific gravity

Conclusion

Dry-mount cytology of the urine sediment is useful in-house to permit more accurate visualization of atypical cells. Urine sediment dry-mount cytology is also particularly helpful when a pathologist’s second opinion is desired about atypical cells identified during urinalysis.

Cytology prepared in this way is indefinitely stable, so the opportunity for cytodiagnosis based on a urine sample is not lost on account of delay associated with transport to the outside diagnostic laboratory.

A common difficulty encountered when interpreting transitional epithelial cell atypia is the mixed-cell population, which refers to observation of inflammation with concurrent cytologic atypia suggestive of malignancy.

Secondary infection is common with transitional cell carcinoma and may be a confounding factor when attempting cytodiagnosis. Transitional cell carcinoma with secondary infection may be cytologically similar to cystitis-induced hyperplasia. In some cases, repeated cytology after resolution of the infection and inflammation, sampling of the mass itself by exfoliative catheterization or FNA, or histopathology may be required for definitive diagnosis.

In this series, all of the patients presented with lower urinary tract signs and atypical transitional cells as part of their urine sediment findings. However, underlying causes, treatment, and prognosis varied. The series underscores the need to evaluate atypical transitional epithelial cells in light of the patient’s signalment, presenting complaint, physical examination findings, other clinical pathology data, and imaging.

FLUTD = feline lower urinary tract disease, FNA = fine-needle aspiration

AMY L. WEEDEN, DVM, is a clinical pathology resident at University of Florida. Dr. Weeden completed a shelter animal medicine and surgery internship at Colorado State University and was an associate in private small animal practice for 8 years before returning to University of Florida for specialty training in clinical pathology. Dr. Weeden received her DVM from Louisiana State University.

HEATHER L. WAMSLEY, DVM, PhD, DACVP, is an assistant professor at University of Florida. She completed 4 years of specialty clinical training: 1 year as a rotating intern at The Animal Medical Center in New York City and 3 years as a resident at University of Florida, after which she earned certification in clinical pathology. Since 2004, Dr. Wamsley has instructed urinalysis and other clinical pathology wet labs at the NAVC Conference, in addition to participating in a hematology masterclass and cytology symposium. She received her DVM at University of Wisconsin–Madison before earning a PhD in molecular biology of infectious diseases from University of Florida.