Assembling a Crash Cart

Liz Hughston, MEd, RVT, CVT, VTS (SAIM, ECC), VetTechXpert

Preparation is key to performing well in any emergency situation, and nowhere is preparation more needed than in assembling the necessary materials to help the veterinary team manage a crashing patient. This collection of materials is often called a “crash cart,” “crash box,” or “crash kit.”

A well-organized, well-stocked crash cart can positively affect cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) outcome, according to evidence-based guidelines developed in 2012 for veterinary patients.1 Responsibility for maintaining and stocking the crash cart should be assigned to specific team members; the cart should be checked at least daily and restocked after each CPR event.

The RECOVER Initiative

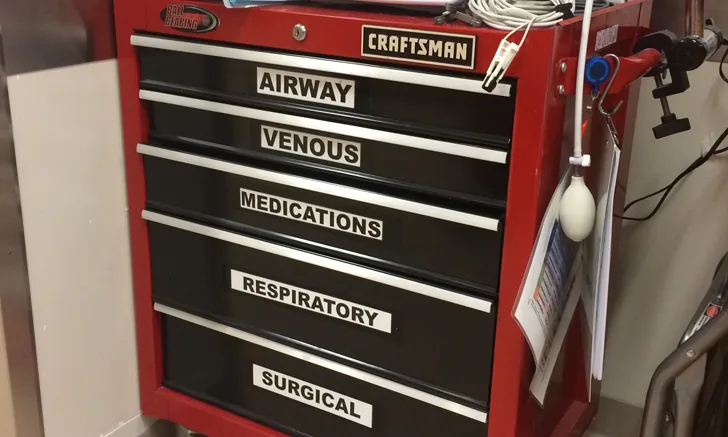

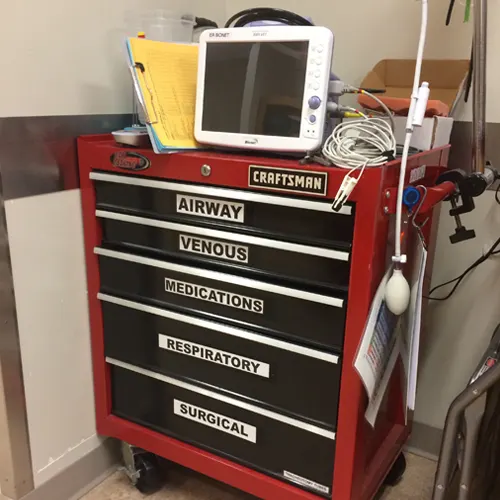

Figure 1. A stocked crash cart

Creating the perfect crash cart to meet a practice’s needs will depend on practice size, number of emergency cases treated, and resources available. Large 24-hour or referral facilities may need large crash carts (see Figure 1), whereas smaller practices or those that treat fewer critical patients may need only a small, well-stocked toolbox to serve as the crash cart.

A crash cart should be portable because emergency situations can occur at any time, and easy accessibility to the needed tools can help the team successfully treat critical patients. Carts should be well-organized and supplies clearly labeled. If the practice has multiple carts in different locations, they should be standardized so all team members can find needed equipment or medications without delay.

If space permits, keep a cart in a well-lit emergency treatment area equipped with a sturdy table and a step stool so team members can deliver chest compressions from the best position possible. An oxygen source must be available; an anesthetic machine can be used for oxygen delivery if necessary.

Stocking the Cart

The Essentials

Whether the practice has a centralized emergency treatment area or multiple carts and treatment areas, every cart should contain some essential equipment:

Endotracheal tubes and ties: To minimize treatment delays, consider avoiding half-sized tubes in the cart so fewer options are available. If the practice size limits the cart to a small box, stocking only even- or odd-sized tubes saves space. After a CPR event, endotracheal (ET) tubes can be replaced for a better fit if necessary. Having ties close at hand (or even pre-tied on the tube) makes quickly securing a tube easier during CPR.

Laryngoscope (with a small and large blade available): The RECOVER guidelines2 call for chest compressions to begin immediately when cardiac arrest is recognized and be continued for 2-minute intervals. This means that most patients will need to be intubated in lateral recumbency during chest compressions. A laryngoscope improves visualization of the larynx and the chances of successful intubation by allowing proper ventilation.

Capnograph: Monitoring end-tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2) is an important monitoring tool for determining the effectiveness of the compressions, with values >15 mmHg (> 2 kPa) indicating good quality compressions. A sudden rise in ETCO2 can indicate the return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) and warrants a shift to post-resuscitation care.2

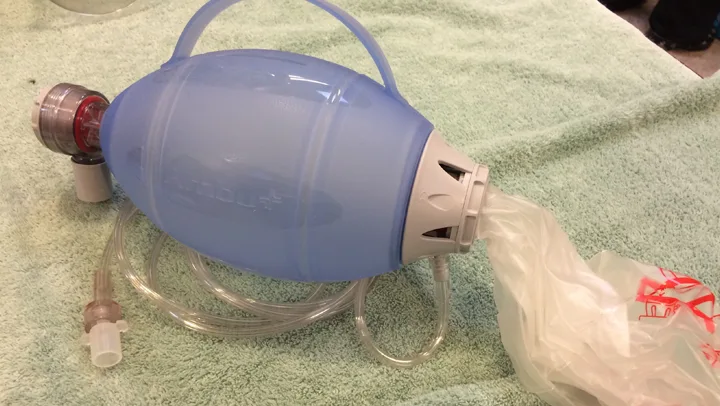

Manual resuscitator: The resuscitator should be connected to an oxygen supply to provide the patient with higher levels of oxygen. (See Figure 2.) However, using a resuscitator with room air can also provide positive-pressure ventilation, a necessity during CPR.

Figure 2. Ambu bags can be used to provide manual ventilation during CPR.

Electrocardiograph (ECG): Identifying the arrest rhythm is an important part of CPR, particularly to identify arrhythmias that may be treated with defibrillation (eg, ventricular fibrillation). ECG instrumentation and rhythm interpretation should not be allowed to interfere with chest compressions.

Syringes and needles: For drawing and administering medications, as well as blood sampling, 1-mL and 3-mL syringes are recommended, along with a selection of 25-, 22-, and 20-gauge needles.

Saline flush: 10-mL syringes preloaded with 0.9% NaCl can be used to flush medications into catheters and to dilute and deliver medications intratracheally if needed. Depending on how frequently CPR is performed at the practice, purchasing sterilized preloaded syringes may be prudent. If CPR is seldom performed, keeping large syringes and bottles of sterile saline available either in the crash cart or in the immediate emergency treatment area is a reasonable alternative.

Red rubber catheters: These catheters can be fed into the endotracheal tube to deliver drugs intratracheally, if needed.

Scalpels: Scalpel blades and handles should be available in case a venous cutdown is needed for emergency venous access or for a tracheostomy, chest tube placement, or open-chest CPR.

Crystalloid fluid sets: Fluid bags prepared with macro-drip administration sets attached will significantly reduce the time required to administer IV fluids, which are often indicated during CPR. Sets preloaded into a pressure infuser may be beneficial but are not essential.

Examination gloves

IV catheters

Tape

Medications should be kept in labeled compartments in the cart so team members can easily recognize and replace missing drugs. Essential medications for a cart, as recommended by the RECOVER Initiative,3 include:

Reversal agents: Reversal agents (eg, naloxone, flumazenil, atipamezole) should be given for any drugs administered before the arrest.

Epinephrine: Low-dose epinephrine administration is indicated for asystole or pulseless electrical activity (PEA) every other 2-minute CPR cycle and, in cases of prolonged ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation (>10 minutes), may be considered every other CPR cycle after administration of atropine and/or lidocaine. High-dose epinephrine should be reserved for prolonged (>10 minutes) CPR.

Atropine: Atropine is indicated for asystole or pulseless electrical activity in patients suspected of having high vagal tone. The drug is routinely used in CPR every other 2-minute CPR cycle, because no evidence indicates harm.

Lidocaine: Lidocaine is indicated for shock-resistant ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia.

Optional Equipment & Medications

The practice may also stock the following in the cart or the emergency treatment area:

Equipment

Defibrillator

Portable suction unit with Yankauer suction tips to clear the oropharynx if intubation is difficult

Thoracocentesis/chest tube kits

Tracheostomy kits

Thoracotomy kits (for open-chest CPR)

Sterile gloves

Sterile gauze

Medications

Vasopressin

Antiarrhythmics (eg, amiodarone, procainamide)

Sodium bicarbonate

Calcium gluconate

Dextrose

Diazepam

Furosemide

Norepinephrine

Dobutamine

Propofol

Additional Resources

The author also recommends keeping cognitive aids with the cart. In an emergency, when a veterinary nurse’s adrenaline is flowing, remembering the CPR steps or drug dosages can be difficult. Cognitive aids and checklists help ensure the CPR team provides patients the best possible evidence-based care.

CPR algorithms are available for purchase at veccs.org.

Large, laminated wall charts to hang in the emergency treatment area also can be purchased from veccs.org.

This article originally appeared in the August 2016 web issue of Veterinary Team Brief.