Anesthesia for Dogs with Myxomatous Mitral Valve Disease

Khursheed Mama, DVM, DACVAA, Colorado State University

Marisa Ames, DVM, DACVIM (Cardiology), University of California, Davis

What is the best approach for anesthetizing animals with myxomatous mitral valve disease?

Proper anesthetic management of patients with cardiac disease depends on the nature and severity of the disease. In a broad sense, the anesthetic approach to the cardiac patient is different for compensated vs decompensated heart disease. In addition, concurrent disease and requisite supportive therapies can cause decompensation of previously compensated heart disease.

Understanding the underlying structural abnormalities and resultant physiologic consequences can influence the anesthesia protocol, periprocedural monitoring, and plans for emergency interventions.

This discussion focuses on the anesthetic management of dogs with varying stages of myxomatous mitral valve disease and commonly observed comorbidities.

Pathophysiology

Myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD) is a degenerative valvular disease in which a portion of the left ventricular stroke volume is regurgitated backward into the left atrium with each contraction. As MMVD progresses, forward stroke volume (ie, flow into the aorta) decreases and the sympathetic nervous system is activated, which results in increased heart rate and contractility. Decreased renal perfusion can also cause the release of renin and activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system.1 This can contribute to sodium and water retention and vasoconstriction, which can cause increased preload and afterload. The neurohormonal activation is compensatory in the short-term, but it can become maladaptive in chronic heart disease.

Additional compensation occurs via cardiac remodeling (eccentric hypertrophy in the case of MMVD), which can help maintain forward stroke volume despite worsening mitral regurgitation. The ventricle has a low-pressure reservoir into which it can eject blood (left atrium), so the wall stress and oxygen demand on the myocardium are only modestly increased in the early and intermediate stages of this disease.2 With chronicity and as the regurgitation increases in severity, systolic function often declines.

Chronic volume overload, progressive cardiac remodeling, and myocardial dysfunction can lead to congestive heart failure (CHF)—a common cause of death due to MMVD.2 Pulmonary edema, a clinical consequence of left-sided CHF, occurs when the pressure in the left atrium and pulmonary venous system rises.1 MMVD is typically a slowly progressive disease; at-home monitoring of resting respiratory rates and exercise tolerance can augment clinical monitoring via radiography and echocardiography.

Other sequelae relating to cardiac remodeling in MMVD include arrhythmia (most commonly atrial premature contractions or atrial fibrillation), compression of the left mainstem bronchus, and cough. Acute CHF can occasionally occur with rupture of a chorda tendinea and an abrupt increase in regurgitant fraction and left atrial pressure. Cardiogenic shock can occur with left atrial rupture caused by hemopericardium and cardiac tamponade.

How is MMVD diagnosed?

MMVD is usually suspected following auscultation of an adult-onset, left apical systolic murmur of mitral insufficiency, often heard around the 5th intercostal space just below the costochondral junction; the palpable apex beat can also serve as a landmark. Because MMVD is characterized by a long preclinical phase, many newly diagnosed dogs may not have clinical signs of heart disease.

Although the presence of a new, left apical systolic murmur in a middle-aged-to- older, small-breed dog can suggest MMVD, confirmation and further staging requires a complete history, physical examination, and additional imaging studies. Clinicians should also evaluate for other diseases that are common in this cohort that can exacerbate and/or complicate MMVD (eg, systemic hypertension due to renal or endocrine disease). This additional testing can provide useful information to help manage patients for both the anesthetic period and the long-term.

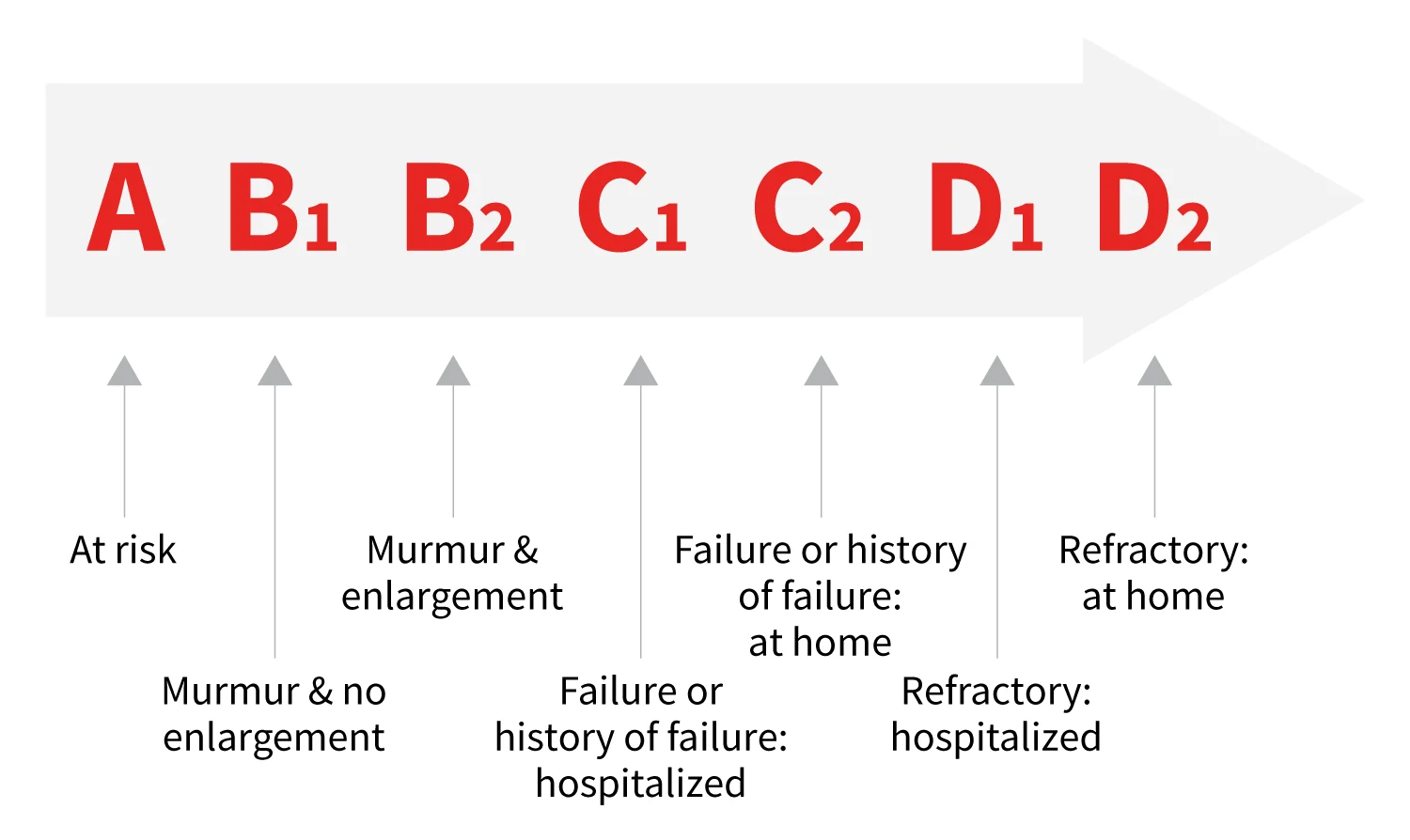

The ACVIM consensus statement offers additional information regarding staging and medical therapy for MMVD (Figure 1).3 Historical and physical examination findings such as exercise intolerance, cough, tachypnea, dyspnea, collapse, end-inspiratory crackles, tachycardia, and arrhythmia should raise concern for decompensating MMVD and/or overt heart failure.

Schematic version of the ACVIM classification for MMVD in the dog. The ACVIM consensus statement lists therapeutic recommendations based on stage of disease.3 Figure courtesy of Clarke E. Atkins, DVM, DACVIM

What are the broad-based considerations?

Patients with early-stage (ACVIM classification of B1) MMVD typically tolerate anesthesia well and do not require special management. Clinicians should maintain the heart rate in the normal range, avoid increases in afterload that may occur with some anesthesia medications, and avoid an increase in preload (as with rapid, high-volume IV fluid administration).

Clinically affected dogs (late stage B2 and stages C and D) are often prescribed chronic medications that include diuretics (eg, furosemide), vasodilators, or ACE inhibitors (eg, benazepril). With disease progression, these patients may also receive drugs that stimulate contractility (eg, pimobendan). Although these chronically administered medications help slow disease progression and minimize consequences to the patient, higher doses and the number of drug classes needed to manage the disease generally reflect increasing severity or disease progression.3

In patients with clinical signs and supporting evidence of disease progression, it is increasingly important to maintain heart rate in a normal-to-high-normal range4,5 while using a conservative fluid administration rate (eg, 2-5 mL/kg/hr) to maintain adequate preload during the anesthesia period. Increases in systemic vascular resistance or afterload should be avoided, as this may increase the fraction of regurgitant flow, which may precipitate heart failure.

How can I best manage anesthesia in a dog with MMVD?

Premedication with an opioid (eg, hydromorphone 0.05-0.1 mg/kg IM or SC or 0.01-0.03 mg/kg IV) can provide mild-to-moderate sedation with minimal cardiovascular side effects. Benzodiazepines (eg, midazolam 0.1-0.2 mg/kg IV or SC or IM) also have few to no cardiovascular effects and can be useful adjuncts in older or sicker dogs. They are, in general, less effective as sole tranquilizers in young or healthy active animals, and they may cause excitement. Alpha-2 agonists are excellent sedatives but are not recommended. They increase systemic vascular resistance and decrease the heart rate, which can increase regurgitant stroke volume while diminishing forward stroke volume. Conversely, acepromazine tends to decrease afterload but can unduly decrease preload and contractility, so its use should be carefully considered.5

Depending on premedication choice and subsequent planned anesthetic medications, an anticholinergic (eg, atropine 0.02-0.03 mg/kg IM or SC, glycopyrrolate 0.01 mg/kg IM) may be added to prevent or offset bradycardia that is commonly seen with use of opioids6 especially following IV administration. It can also maintain the heart rate in a normal range; tachycardia should be avoided, as this can negatively affect ventricular filling. Treatment with an anticholinergic may be considered as an alternate strategy only in cases of observed bradycardia or bradyarrhythmias. In the authors’ observation, this strategy commonly results in an exacerbation of bradycardia and/or bradyarrhythmias with low-dose anticholinergic administration and tachycardia with high-dose anticholinergic administration.

For a patient with mild- (stage B1) to- moderate (early-to-intermediate stage B2) MMVD, the veterinarian may choose his or her preferred IV induction agent and titrate to the desired end point. Propofol and alfaxalone are acceptable for dogs with mild disease and may be used judiciously in patients with moderate disease.7-9 Ketamine similarly has indirect sympathomimetic actions and can help maintain heart rate and cardiac output in dogs with mild-to-moderate disease.10 A dose of ketamine (5-7 mg/kg IV) with midazolam (0.2-0.3 mg/kg IV) can provide intubation conditions in premedicated dogs. Alternatively, lower doses of ketamine (2-3 mg/kg IV) may be used in combination with similar doses of propofol titrated to effect in dogs with mild-to-moderate disease.

Anesthesia induction for patients with advanced disease can be more safely accomplished using drugs with a low likelihood of or manageable cardiovascular depression, such as a combination of an opioid (eg, fentanyl 10 µg/kg IV)11,12 or etomidate (1-2 mg/kg IV)13 and a benzodiazepine (eg, midazolam 0.1-0.2 mg/kg IV). Bradycardia is likely with IV opioids, and it can be mitigated with use of anticholinergics. A small dose (0.5-1.0 mg/kg IV) of a hypnotic agent (eg, propofol) or alfaxalone may be necessary to facilitate intubation. Data on alfaxalone’s cardiovascular effects in this patient population are limited.

Patients with severe heart failure secondary to mitral insufficiency are at greater anesthetic risk; elective surgery should be postponed for these patients until the condition is controlled or stabilized with medical management. If this is not possible, careful titration of a benzodiazepine with a nonhistamine releasing µ-opioid agonist or etomidate still provides the safest option for anesthesia induction. Preplacement of heart rate, rhythm, and blood pressure monitoring equipment and availability of supportive medications are strongly recommended in these animals.

Maintenance with inhalation anesthetics is appropriate for dogs with mild-to-moderate disease. Supplemental analgesia should be provided as needed. In dogs showing clinical signs of heart failure, a balanced technique including high doses of an opioid (eg, fentanyl 20-40 µg/kg/hr) can allow for a reduction in the dose of inhalation agents and, in turn, their dose-dependent myocardial depressant effects.

High-dose opioid infusions can cause respiratory depression. Alternative approaches using anesthetic-sparing infusions of ketamine (20 µg/kg/min) and lidocaine (30-50 µg/kg/min) with lower doses of nonhistamine-releasing opioid infusions (eg, hydromorphone 0.02-0.03 mg/kg/hr) may be considered if mechanical ventilation is not possible. Consultation with or referral to a board-certified anesthesiologist should be considered in dogs with advanced (stages C and D) disease.

Should cardiac medications be withdrawn before anesthesia?

Some anesthesiologists recommend withdrawal of ACE inhibitors on the day of anesthesia because of the potential for hypotension,14,15 but some reports in human patients suggest no greater incidence of hypotension when these medications are given the morning of surgery; some benefits have also been noted.16,17 These differences may be explained by different degrees of left ventricular function in patients as well as different anesthesia protocols. This lack of consensus—even among physicians18,19—leaves the decision up to each veterinarian. The authors’ preference is to not withdraw these cardiac medications if the dog’s cardiac disease is well-managed with them.

Clear guidelines exist for withdrawal of warfarin and heparin therapy from human patients. Information remains limited in veterinary medicine, especially for newer anticoagulants with unique mechanisms of action.

How do I provide proper perianesthesia management of common anesthetic complications & comorbidities?

Even when receiving an anesthetic protocol that is selected to minimize adverse events, dogs may become hypotensive during an anesthetic event. This can be challenging, even in dogs presented for elective procedures. The traditional approach of IV crystalloid or synthetic colloid boluses for hypotension can cause volume overload in the heart.

Because of the potential for sustained expansion of vascular volume with colloids, the authors use crystalloids for vascular volume expansion in these patients. In case of an accidental crystalloid overdose, administration of furosemide (1 mg/kg IV) can help alleviate negative consequences (eg, pulmonary edema).

It is prudent to have available drugs that support the cardiovascular system. In general, targeting the cause of low blood pressure (if known) is best. Therapy may involve simply increasing an abnormally low heart rate with an anticholinergic to improve cardiac output and forward stroke volume. Drugs that improve contractility (eg, dobutamine CRI of 2-7 µg/kg/min IV) are ideal in dogs with myocardial failure. Ephedrine (0.05-0.1 mg/kg IV) and dopamine (CRI of 2-5 µg/kg/min IV) may also safely provide cardiovascular support.4

Dopamine has the presumed added benefit of enhancing renal perfusion in dogs when used at low doses and is a good choice if renal insufficiency is a comorbidity. High doses (>10 µg/kg/min) of dopamine and other medications with a-adrenergic effects should generally be avoided because of potential to increase afterload.

Dysrhythmias may be observed in the perianesthetic period, and they are more likely to be observed in dogs with myocardial failure. In addition to addressing common perianesthetic causes (eg, hypoxia, hypercapnia, light plane of anesthesia), treatment may be necessary if there is a risk for progression of dysrhythmias (eg, ventricular ectopy to tachycardia or fibrillation) or if tissue perfusion is compromised.

Lidocaine (1-2 mg/kg IV as bolus, followed [if needed] by a CRI of 75-100 µg/kg/min) is a good first-line choice for treatment of dogs with ventricular dysrhythmias. It also has the benefit of synergistic effects with other anesthetic agents. Signs of atrial tachydysrhythmias (eg, poor ventricular filling because of high heart rate and loss of the atrial kick [ie, when the atrial contraction adds preload to the ventricle immediately before ventricular systole, which increases the volume ejected from the ventricle]) may be alleviated with b-blocking drugs (eg, esmolol) or calcium-channel blockers (eg, diltiazem), but both can cause hypotension and must be used judiciously. Electrical cardioversion may also be attempted for atrial fibrillation, but it is likely not broadly available.