Actinomyces spp & Nocardia spp

J. Scott Weese, DVM, DVSc, DACVIM, FCAHS, University of Guelph, Ontario, Canada

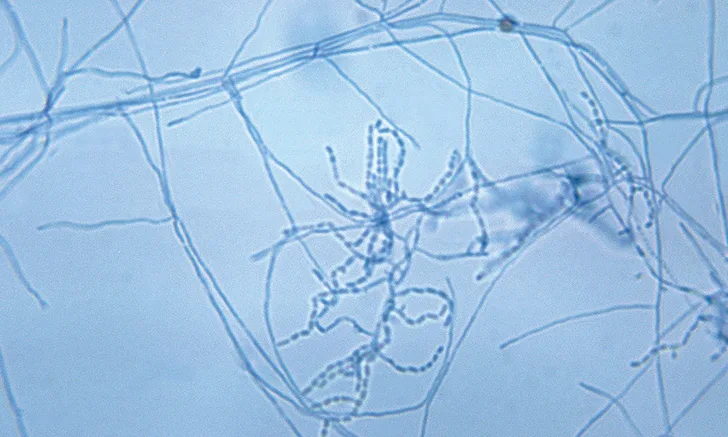

Gram stain of Nocardia asteroides. Note the branching filamentous bacteria that may terminate in a rod and coccus shape. Image courtesy of US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Actinomyces spp and Nocardia spp are members of class Actinobacteria, which can cause opportunistic infections in dogs, cats, and other species. Both can cause pyogranulomatous or suppurative disease that is often slowly progressing and challenging to diagnose; however, some differences in organism and characteristics exist (Table 1). The incidence of disease caused by either is undefined and likely low.

Table 1: Comparison of Actinomyces spp & Nocardia spp

Actinomyces spp

Many different species are present, and taxonomy continues to change; some species previously known as Actinomyces have been reclassified in other genera, such as Arcanobacterium spp and Trueperella spp. Regardless, disease aspects remain unchanged. Commonly found as part of the oral, GI, and genital microbiotas,1-3 Actinomyces spp and related genera are of limited virulence unless inoculated into tissue (eg, via bites, foreign bodies, or trauma).

Four main types of infection can be encountered: cervicofacial, thoracic, abdominal, and subcutaneous.4-9

Clinical signs correspond to the tissues involved and the severity of disease.

Disease is often associated with firm and fibrous masses, persistent exudates (eg, pyothorax7,10), draining tracts, abscessation, and osteomyelitis.

Nocardia spp

The Nocardia genus contains more than 30 saprophytic species that are widely, if not ubiquitously, disseminated in the environment. Disease occurs following inoculation of the bacterium into tissue or via inhalation.

Nocardia spp are regionally variable, with higher rates of infection in dry, dusty, and windy regions (eg, southwestern United States, parts of Australia).

Nocardiosis is classically divided into 3 clinical forms: pulmonary, disseminated (systemic), and cutaneous/subcutaneous.11-15

Clinical presentations are as would be expected with pulmonary, systemic, or cutaneous infections. Pulmonary or cutaneous disease can progress to disseminated disease.

Diagnosis

Early diagnosis may be missed. These infections are often only considered in chronic cases.

Neoplasia is sometimes suspected based on the types of lesions and failure to respond to empirical antimicrobials.

Cytologic examination of aspirates or exudates, as well as histopathology, is critical for diagnosis because the filamentous nature of these bacteria is unlike typical pathogens.

Acid-fast staining should be performed.

Presence of visible sulfur granules should prompt strong suspicion of Actinomyces spp infection.

Isolation of other pathogens does not rule out these organisms; thus, reliance on culture as the first step is unwise.

Actinomyces spp often coaggregates with other bacteria and may be overlooked when a common, easily grown pathogen (eg, Staphylococcus spp) is isolated.

Isolation of Actinomyces spp and Nocardia spp can be difficult, as they are slow growing and may be overgrown by contaminants of coinfecting bacteria.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing is often not available because of the slow-growing nature of these organisms and lack of standard testing guidelines.

Negative culture results do not rule out the presence of these bacteria.

Common Treatment Options for Actinomyces spp & Nocardia spp Infections

Treatment

Optimal antimicrobial regimens have not been established, but differentiation between these similar pathogens is important, as empirical treatment recommendations differ (Table 2).

Surgical resection of densely infected soft tissue may be beneficial or required.

Accumulations of exudates (eg, pyothorax) should be removed.

Underlying causes such as a penetrating foreign body should be part of the initial diagnostic and treatment plan.

For Nocardia spp infection, consideration of a possible underlying immunosuppressive disorder that could impact long-term prognosis is indicated.

Duration of treatment is not well understood, but weeks to months of antimicrobial therapy are usually required, often with the approach of continuing for a few weeks after clinical resolution.

Many months of treatment may be required in patients with disseminated disease.

Prognosis is variable and depends on severity and location of infection.

For Actinomyces spp infection, the prognosis is fair to good, particularly if affected tissue can be resected or if there is no extensive systemic involvement.

For Nocardia spp infection, the prognosis is guarded, especially in patients with disseminated or pulmonary disease.

Zoonotic Potential

Although both pathogens can affect humans, there is little evidence that infected animals pose a zoonotic risk.

Infected animals represent only one possible source of exposure.

Basic infection control and hygiene practices to limit exposure (eg, hand hygiene, covering open wounds when handling an infected patient, safely handling sharps) should be taken, but specific measures are not indicated.