Abdominal Palpation in Dogs & Cats

Alice Defarges, DVM, MS, DACVIM, University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario, Canada

Allison Collier, DVM, DVSc, University of Guelph

Abdominal palpation can help identify and localize abdominal pain during physical examination. Pathology (eg, abdominal masses, organomegaly) may be identified via palpation before development of clinical signs. Palpation should be learned through practice, ideally with a mentor, and repeated if abnormalities are missed on palpation but subsequently identified on imaging.

Distance Examination

Prior to palpation, the contour of the abdomen can be visually assessed (Figure 1). An abnormal contour (eg, disappearance of the flank or abdominal tuck) can indicate abdominal enlargement; differential diagnoses include obesity, pregnancy, organomegaly, and ascites.

Normal abdominal contour (A); abnormal abdominal contour and abdominal enlargement caused by ascites (B)

Assessing position and demeanor can also be beneficial. Patients with abdominal pain may be unwilling to roll onto their back, and patients with cranial abdominal pain may demonstrate prayer position (ie, lowered cranial half of the body and raised caudal half; Figure 2).

Prayer position, which often indicates cranial abdominal pain

Palpation Technique

Abdominal palpation can be performed using the PALPATE (ie, position, anatomy, level, pressure, assessment, thorough systematic approach, extra-abdominal assessment) technique.1

Step-by-Step: Abdominal Palpation

Step 1

Position

Provide a comfortable, safe position for the clinician and patient (ie, table for small dogs or cats, floor for large dogs) in a quiet, calm environment. If palpation is challenging (eg, patient is obese, tense, painful, or stressed), try placing the patient in lateral recumbency.

Author Insight

An assistant should be present to restrain the patient.

Step 2

Anatomy

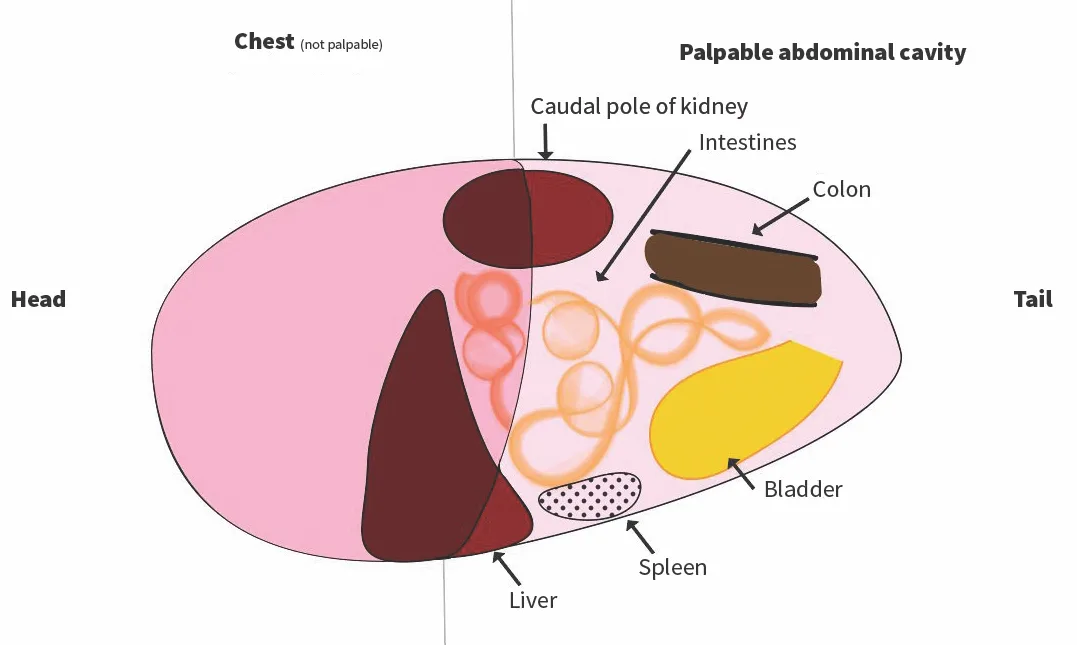

Visualize the 3D orientation of abdominal organs (see Approximate Location of Organs in the Abdominal Cavity).

APPROXIMATE LOCATION OF ORGANS IN THE ABDOMINAL CAVITY

Cranial abdomen

Stomach

Liver

Spleen

Pancreas

Mid-abdomen

Spleen

Kidneys (dorsal)

Adrenal glands (dorsal)

Small intestine

Caudal abdomen

Urinary bladder

Prostate

Uterus

Colon

Small intestine

Author Insight

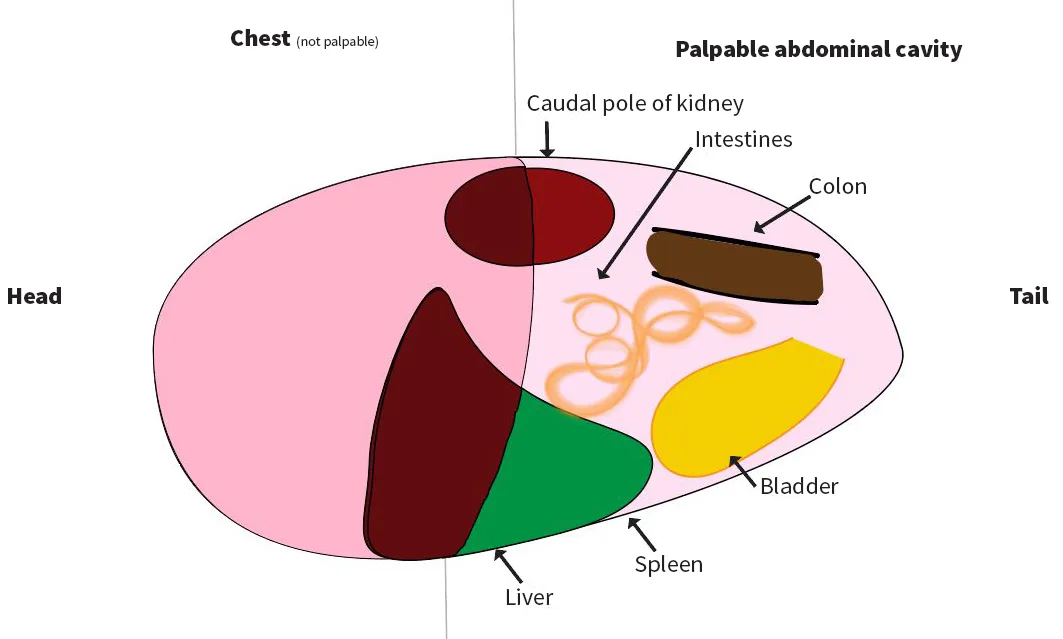

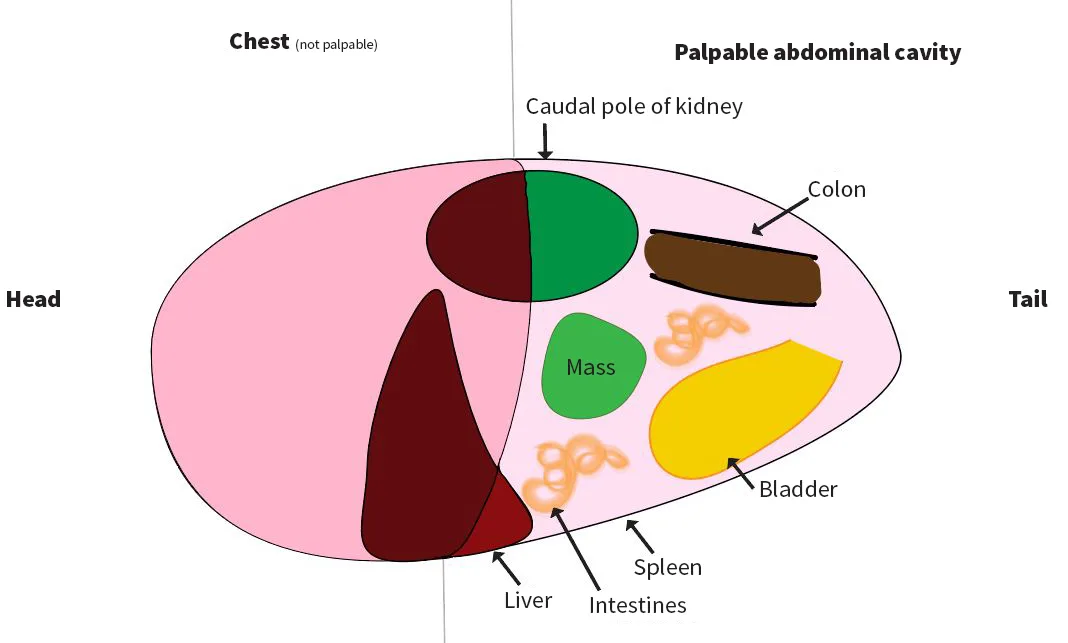

Abdominal organ location varies among normal patients (A), patients with hepatomegaly (indicated by the liver extending beyond the costal margin; B), and patients with an abdominal mass (C). Understanding which organs are normally palpable or nonpalpable can help identify abnormalities (see Palpable & Nonpalpable Organs on Normal Abdominal Palpation).

PALPABLE & NONPALPABLE ORGANS ON NORMAL ABDOMINAL PALPATION

Palpable

Intestines, colon

Bladder (if full)

Both kidneys (cats); ± caudal pole of left kidney (dogs)

Tail of spleen

Nonpalpable

Liver

Pancreas

Stomach

Adrenal glands

Uterus (except with pregnancy or pyometra)

Ovaries

Lymph nodes

Step 3

Level

Avoid superficial palpation that only detects abdominal wall musculature and deep palpation that can cause pain.

Clinical Skills You’ll Want to Keep

Get this guide in a free downloadable resource, along with guides to 5 more cornerstone skills you'll want to have in your back pocket. From choosing the correct fluid type to performing a neurological examination, Practical Guidance for New Veterinarians is your key to starting practice with confidence.

Step 4

Pressure

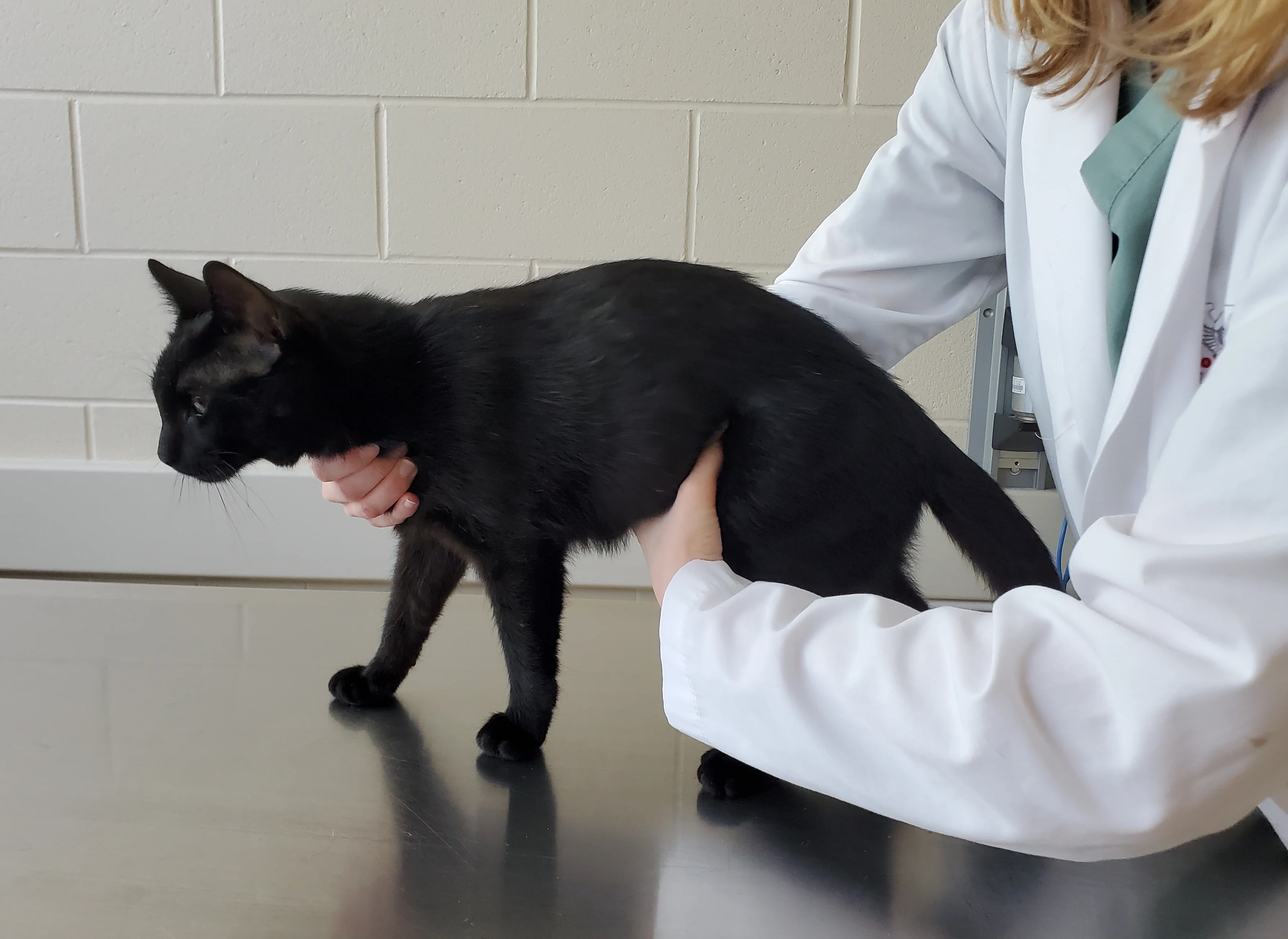

Apply gentle, progressive pressure on the abdomen. To appreciate organ shape and size in medium and large dogs, hold the abdomen between both hands (ie, 2-handed technique; A). For cats and small dogs, hold the abdomen between the thumb and fingers of one hand (ie, one-handed technique; B).2,3 Bring the fingers together with a light but forceful touch, and move the fingers in a dorsal to ventral direction.

Author Insight

Gentle palpation is recommended in postoperative patients and those with either suspected hemoabdomen or urethral obstruction to avoid hemorrhage from a mass or bladder rupture, respectively.

Step 5

Organ Assessment

Use the fingertips to sense the size and shape of organs and detect abnormalities (eg, masses, pain, abdominal distension, organomegaly, foreign objects).

Liver

Palpate the cranial abdominal cavity beneath the costal arch; hepatomegaly is commonly indicated if margins of the liver extend beyond the rib cage.

Spleen

Palpate the mid-abdomen, usually on the left side. The tail of the spleen may be felt on the ventral abdominal floor in a normal dog in a recumbent position.

Kidneys

Palpate the dorsal abdomen.

Author Insight

Only the caudal poles of the kidneys are palpable in dogs. In some dogs, the entire right kidney is in the rib cage, and in other dogs, neither caudal pole may be palpable because of surrounding musculature and adipose tissue. Both kidneys are palpable in cats and are more mobile than in dogs, allowing assessment of shape, contour, and symmetry. Because feline kidneys can be incorrectly palpated as one large kidney, one hand should be kept still while the other hand is moved to separate the kidneys.

Intestines

Place the fingers on either side of the mid-abdomen, press the fingers toward each other, and move them in a dorsal to ventral direction; loops of intestines may be felt slipping through the fingers. Assess the intestines for thickening, masses, intussusception, and foreign objects.

Palpate the dorsal abdomen; the colon may be felt as a tubular structure if filled with feces. Fecal material is typically compressible; do not confuse fecal material with an abdominal mass.

Author Insight

Although characterization of an abdominal mass via palpation can raise suspicion for differential diagnoses, palpation is rarely diagnostic. Imaging studies are usually required to better locate and characterize a mass.

Bladder

Palpate the caudal abdomen for a fluid-filled balloon-like structure; the urinary bladder is often pear-shaped in dogs and spherical in cats. Assess size and firmness; the bladder is often firm and round in patients with urethral obstruction. Palpate gently if an obstruction is suspected to avoid bladder rupture.

Step 6

Thorough Systematic Approach

Use a consistent technique (eg, cranial to caudal, dorsal to ventral) to ensure all areas of the abdomen are evaluated and none are missed, which could result in unidentified lesions and inaccurate diagnoses.

Step 7

Extra-Abdominal Assessment

Palpate the back for pain that may confound abdominal palpation findings. Evaluate the abdominal wall for hernias, lipomas, masses, evidence of skin disease, and evidence of dermatologic lesions (eg, petechiae and ecchymoses, both of which may be indicative of coagulopathy and warrant more gentle palpation).

Fluid Wave Technique

Assessing for abdominal fluid during abdominal palpation is important, as a fluid wave can suggest ascites.

Step-by-Step: Fluid Wave to Assess for Abdominal Fluid

Step 1

Place one hand on either side of the abdomen.

Step 2

Perform gentle ballottement of the abdomen with one hand, keeping the other hand in a fixed position on the opposite side of the abdomen for at least 3 to 5 seconds to allow the impulse to be transmitted through the abdominal fluid (if a fluid wave is present) and perceived (ie, tap; Video).

Video

Author Insight

A minimum of 30 to 40 mL/kg of peritoneal fluid is necessary for detection of a fluid wave.4 Lack of a fluid wave thus does not rule out ascites, and presence of a fluid wave does not indicate the cause of ascites.