Abdominal Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma

David M. Schmidt, DVM, DACVR, Massachusetts Veterinary Referral Hospital, Woburn, Massachusetts

More than 10 years ago, a novel ultrasound protocol, abdominal focused assessment with sonography for trauma (aFAST), was described in veterinary literature1 and has changed the way emergency patients are evaluated for intraabdominal trauma. One of the most common signs of abdominal trauma is detection of free fluid within the peritoneal space. Most frequently, this fluid is a result of hemorrhage from blunt force trauma to the spleen or liver, although rupture of the urinary bladder or gallbladder is also a source of abdominal fluid in emergency patients. Before the widespread use of ultrasonography, blind abdominocentesis and radiography were the most readily available techniques to assess patients for peritoneal fluid. However, radiography has been shown to be less sensitive than ultrasonography, with ultrasonography experimentally being up to twice as sensitive as radiography with relatively small amounts of fluid (up to 2 mL/lb).2

Related Articles

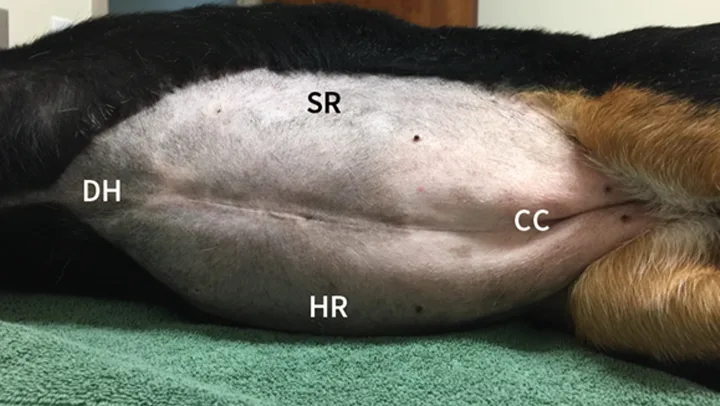

The clock-face analogy, showing a dog’s abdomen divided into 4 quadrants.

Although veterinary radiologists and trained ultrasonographers were detecting abdominal fluid long before the aFAST protocol was described, the goal of the initial study was to show that individuals without clinical ultrasonographic experience could identify free abdominal fluid with adequate accuracy.1 Of the 100 aFAST examinations performed in the study, later review by a radiologist found only 2 instances in which the clinician made a diagnosis of “no fluid” when fluid was detected on the saved images (ie, false negative diagnosis).1 However, the true number of false negatives may be higher as images were not rescanned by a skilled ultrasonographer. In reality, any additional true negative diagnoses are likely due to less than 2 mL/lb of abdominal fluid, which are most likely clinically insignificant, and the aFAST examination is still a good point-of-care test.

The aFAST examination may be performed with the patient in lateral or dorsal recumbency. Traumatic wounds (eg, flail chest) may dictate which position to use. Right lateral recumbency is often the position of choice, as it facilitates examination of the heart when performed as part of a thoracic FAST (tFAST) examination.3 Lateral recumbency generally eases respiratory effort compared with dorsal recumbency.

The aFAST examination divides the abdomen into 4 quadrants. A good way to perform the examination is to use a clock-face analogy and begin at the 12-o’clock position (Clock-face). The starting position, designated the diaphragmatic–hepatic (DH) position, is caudal to the xiphoid process; it is useful for finding fluid between liver lobes and the diaphragm. The next quadrant lies at the 3-o’clock position over the left flank and is designated the spleno–renal (SR) position. Both the spleen and left kidney should be visible within this region. At the 6-o’clock position over the caudal abdomen, the urinary bladder and colon can be seen, making this window the cysto–colic (CC) position. The final quadrant within the aFAST examination is over the right flank at the 9-o’clock position, designated the hepato–renal (HR) position. The right kidney and liver should be visible within this region.1,4

Related Articles

Step-by-Step: Abdominal Focused Assessment With Sonography for Trauma

What You Will Need

Ultrasound machine

Ultrasound transducer (probe)

Coupling gel

Alcohol

Clippers

Author Insight

With an average examination time of 6 minutes or less, aFAST can be performed quickly and while other diagnostics or stabilizing procedures are performed by additional team members.

STEP 1

Place the patient in right lateral recumbency (unless traumatic injuries dictate otherwise). Use clippers to remove fur (at least a 4- to 5-cm square) from the 4 quadrants to be examined. Apply coupling gel to the ultrasound probe or liberally use isopropyl alcohol to wet the skin.

Conclusion

Applying the abdominal fluid scoring (AFS) system when evaluating each quadrant of the abdomen during the aFAST examination may be useful. The AFS is a 4-point scale that starts at 0 (negative for peritoneal fluid). One point is assigned for each quadrant in which fluid is identified, up to 4 points total. The amount of fluid in a particular quadrant does not affect the score (ie, any amount of fluid, minimal-to-severe, receives the same point value of 1). It is important to note that AFS scores are only validated in dogs when the examination is performed with the patient in right lateral recumbency. Dogs with AFS scores of 3 and 4 are more likely to require blood transfusions compared with dogs with AFS scores of 0 to 2.4

As with many skills in veterinary medicine, becoming proficient at the aFAST examination and maneuvering the ultrasound probe requires practice. The aFAST examination can be easy to learn and a good way to identify peritoneal fluid in patients with recent motor vehicle trauma. The aFAST examination also has applications in patients that present with an acute abdomen but no known trauma. With gained proficiency, clinicians may be able to diagnose other conditions (eg, splenic mass, gallbladder mucocele) that could require acute intervention.

aFAST = abdominal focused assessment with sonography for trauma, AFS = abdominal fluid scoring, CC = cysto–colic, DH = diaphragmatic–hepatic, HR = hepato–renal, SR = spleno–renal, tFAST = thoracic focused assessment with sonography for trauma