Feline Triaditis

Profile

Definition

Feline triaditis is the concurrent presence of inflammatory disease of the liver, the pancreas, and the intestines in a cat. The term is somewhat of a misnomer and stands in contrast to the use of the term in human medicine, where it denotes an inflammatory condition involving hepatic triads and adjacent connective tissue.

Concurrent inflammatory disease of the liver, the pancreas, and the intestines have been described in several case reports.1-4 In a landmark paper, Weiss and colleagues5 described the correlation of inflammatory disease of these 3 organs in a large group of cats. In this study, 83% of cats with cholangiohepatitis also had IBD, 50% had concurrent pancreatitis, and 39% had both concurrent IBD and pancreatitis. Interestingly, the rate of concurrent nephritis was similar in cats with cholangiohepatitis and those without inflammatory conditions of the liver.

While the rates of IBD and pancreatitis are higher in cats with cholangiohepatitis than in cats without cholangiohepatitis, a cause-and-effect relationship among these 3 inflammatory conditions has not been described. Several hypotheses have been advanced as to how these conditions could be related, but none has been experimentally explored. Thus, this relationship remains merely speculative.

Systems

Hepatobiliary, exocrine pancreas, and the small intestines are affected.

Genetic Implications

A genetic predisposition for cholangiohepatitis, pancreatitis, or IBD in cats has not been reported.

Several forms of IBD are associated with a genetic predisposition in humans, but such a predisposition has not been explored or described for cats.

Incidence/Prevalence

Cholangiohepatitis, pancreatitis, and IBD all are very common in cats.

Geographic Distribution

All 3 conditions are found worldwide.

Signalment

Species: cat

Breed predilection: none known

Age and range: Cholangiohepatitis can occur at any age but is most commonly seen in middle-aged to older cats; pancreatitis and IBD can occur at any age.

Gender: There is no gender predilection for cholangiohepatitis, pancreatitis, or IBD.

Causes

Cholangiohepatitis in cats is probably initiated by bacteria ascending through the bile duct. An immune response to bacterial antigens may result in perpetuation of the inflammation.

The cause of pancreatitis remains unknown in most cases.

The cause of IBD is unknown. However, it is speculated that IBD is the result of an abnormal interplay between antigenic stimulation (eg, by dietary or infectious antigens) and the immune system.

Risk Factors

No known risk factors exist for cholangiohepatitis and IBD.

Risk factors for feline pancreatitis include hypercalcemia, hypertriglyceridemia, trauma, hypotension, toxins, pharmaceutical agents, and a small group of infectious organisms.

Pathophysiology

Cholangiohepatitis, and more specifically, acute cholangiohepatitis, is often associated with a bacterial infection. The inflammatory reaction seen results from this bacterial infection.6

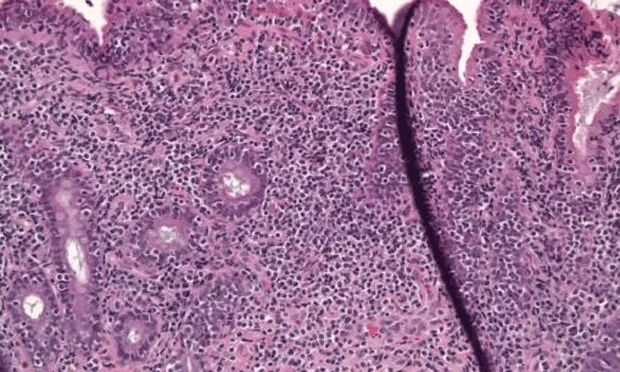

IBD is associated with infiltration of the gastrointestinal mucosa with inflammatory cells (Figure 1), which is speculated to occur because of unusual stimulation of a normal enteric immune system or the usual stimulation of a hyperreactive immune system.7

Pancreatitis is associated with autodigestion of the pancreas and infiltration with inflammatory cells. In patients with chronic pancreatitis, as is seen in connection with triaditis, the inflammatory infiltrate consists mostly of lymphocytes.8

It is unknown whether these 3 diseases are related by a true cause-and-effect relationship, and, if so, which of these 3 conditions occurs first. However, given that cholangiohepatitis can have a bacterial cause and both IBD and pancreatitis are not infectious in origin, one may speculate that cholangiohepatitis occurs first.

Signs

History

Clinical signs frequently reported include anorexia, diarrhea, vomiting, weight loss, and lethargy.6,9,10

Physical Examination

In early, mild cases: often no abnormal findings

In more severe cases: icterus

In chronic, mild cases: poor hair coat, poor body condition

Pain Index

Cholangiohepatitis may be associated with mild abdominal discomfort.

Pancreatitis is often associated with abdominal discomfort and pain. Although many cats do not display overt signs of abdominal discomfort, analgesic therapy should be routinely provided for cats with pancreatitis.

Diagnosis

Definitive Diagnosis

Definitive diagnosis of cholangiohepatitis requires a liver biopsy.

Definitive diagnosis of pancreatitis requires a pancreatic biopsy; a presumptive diagnosis can be based on ultrasonographic changes and/or an elevation of serum fPLI concentration (≥ 12 µg/L).

Definitive diagnosis of IBD requires intestinal biopsies; a presumptive diagnosis can be based on chronic gastrointestinal signs combined with cobalamin deficiency that responds to a dietary trial or immunosuppressive therapy and cobalamin supplementation (the latter when cobalamin deficiency is present).

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses for triaditis include isolated cholangiohepatitis, pancreatitis, IBD, other chronic hepatic diseases, hyperthyroidism, renal failure, and other primary chronic gastrointestinal diseases (eg, gastrointestinal lymphoma).

Laboratory Findings/Imaging

Cholangiohepatitis and pancreatitis can be associated with neutrophilia with a left shift and sometimes anemia.

The most consistent findings in cats with cholangiohepatitis are hyperbilirubinemia and elevated liver enzyme activities.

Pancreatitis is associated with a variety of nonspecific biochemical changes that are mostly dependent on disease severity.

IBD is often associated with mildly elevated serum alkaline phosphatase activities.

Abdominal radiographs are not specific for any of the 3 conditions and are usually normal.

Abdominal ultrasonography may show a thickened gallbladder wall or a dilated bile duct with cholangiohepatitis; hypoechogenicity or hyperechogenicity of the pancreas may be seen in cats with pancreatitis; thickened bowel loops can be seen in cats with IBD.

Treatment

Inpatient or Outpatient

Inpatient versus outpatient treatment depends on disease severity. Most cats with triaditis have mild disease and can be treated on an outpatient basis.

When cholangiohepatitis is suspected to be of bacterial origin, the most important component of triaditis therapy is appropriate antibiotic therapy (ideally based on bacterial culture and susceptibility).

Cholangiohepatitis therapy can be further supported by use of ursodeoxycholic acid or SAMe.

Pancreatitis should initially be managed by evaluation for risk factors (eg, medications, hypercalcemia, hypertriglyceridemia), potentially feeding a low-fat diet, and monitoring disease severity.

IBD should initially be treated with dietary trials, cobalamin supplementation if cobalamin deficiency is present, and an antibiotic trial (eg, tylosin) if there is no response to initial therapy.

Steroids and other immunosuppressive agents should not be used until the bacterial component of cholangiohepatitis or cholangitis has been ruled out, deemed to be highly unlikely, or has been successfully addressed.

Activity

No restrictions

Client Education

All 3 components of triaditis are chronic diseases that can be challenging to manage.

Nutritional Aspects

There are a variety of nutritional considerations that do not always agree:

Cholangiohepatitis does not require a special diet unless it is complicated by hepatic lipidosis or hepatic failure.

While a cause-and-effect relationship for a high-fat diet and pancreatitis has never been demonstrated for cats, it appears prudent to feed a low-fat diet in these patients if possible.

IBD can be addressed nutritionally with dietary trials; choose 1 of 3 general approaches:

Diets with 1 protein source and 1 carbohydrate source

Hydrolyzed protein diets

Easily digestible diets

Medications

Drugs/Fluids

Antibiotics: various, based on culture and sensitivity

Choleretic: ursodeoxycholic acid, 10 to 15 mg/kg orally Q 24 H

Antioxidant: SAMe, 18 mg/kg orally Q 24 H (round to next closest tablet size)

Pain medications: various, as needed.

Antiemetic: dolasetron, 0.6 mg/kg subcutaneously or orally Q 12 H

Immunosuppressive agent (only after cholangiohepatitis has been sufficiently addressed): prednisone, 1 to 2 mg/kg orally Q 12 H (decreasing dosing schedule)

Contraindications

Immunosuppressive agents should not be used until the bacterial component of cholangiohepatitis or cholangitis has been ruled out, deemed to be highly unlikely, or has been successfully addressed.

Follow-Up

Patient Monitoring

At least weekly initially

Chemistry profile to monitor cholangiohepatitis

Serum fPLI concentration to monitor pancreatitis

Prevention

None known

Complications

Triaditis can be associated with such complications as hepatic lipidosis, hepatic failure, or fulminant exacerbation of pancreatitis.

Course

The infectious component of cholangiohepatitis can often be successfully managed.

The inflammatory component of chronic cholangiohepatitis, pancreatitis, and IBD is often difficult to manage and is associated with a chronic course.

At-Home Treatment

Unless triaditis is associated with complications, patients can mostly be treated at home.

In General

Prognosis

Short-term: fair

Long-term: guarded

Relative Cost

Proper diagnosis: $$$$-$$$$$

Short-term management: $$$

Long-term management: $$$$$

Future Considerations

Much remains to be studied concerning feline triaditis or the 3 conditions that are part of this disease complex.

The cause-and-effect relationship, if any, among cholangiohepatitis, pancreatitis, and IBD needs to be elucidated.

Noninvasive diagnostic tests for cholangiohepatitis and IBD need to be developed.

More effective treatment strategies for feline triaditis need to be established; much work is being done to determine the clinical usefulness of modulators of inflammatory mediators.

TX at a glance

Suppurative cholangiohepatitis needs to be treated with appropriate antibiotic therapy. Chronic lymphocytic cholangiohepatitis or cholangitis may require corticosteroid therapy.

Cholangiohepatitis therapy can be supported by use of ursodeoxycholic acid and SAMe.

Analgesic and antiemetic therapy should be provided as needed.

Immunosuppressive therapy should be used only after the bacterial component of cholangiohepatitis or cholangitis has been ruled out, deemed to be highly unlikely, or has been successfully addressed.