Surgical Drains for Wound Management

Brett Darrow, DVM, University of Tennessee

Cassie Lux, DVM, DACVS (SA), University of Tennessee Veterinary Medical Center

Surgical drain placement, an important component of traumatic and surgical wound management, is designed to remove accumulated fluid that may provide a growth medium for bacteria, evacuate inflammatory debris, and lessen pain associated with pressure and inflammation.1,2 Drains can promote tissue layer adhesion by removing fluid barriers and, specifically, closed drains can provide active negative pressure. However, drains also can introduce complications (eg, ascending infection) and incite an inflammatory response.

When patients incur traumatic or surgical wounds, drain placement should be based on several factors, such as presence of contamination or infection, likelihood of fluid accumulation postoperatively, whether open or closed wound management can be implemented, and the amount of dead space present; all of these factors are implicated in pain levels, increased infection rates, and delayed healing.1,2 Drains can be used when wounds contain extensive pocketing, have mild-to-moderate wound contamination that can be converted to clean wound beds, and are free of foreign debris or fibrotic/necrotic tissue. Drains also can be especially useful in patients with highly effusive wounds. However, drains should not be a substitute for thorough wound exploration, debridement, and lavage, nor should they supplant the need for open wound management.

Related Article: Online Gallery: A Look at Basic Wounds

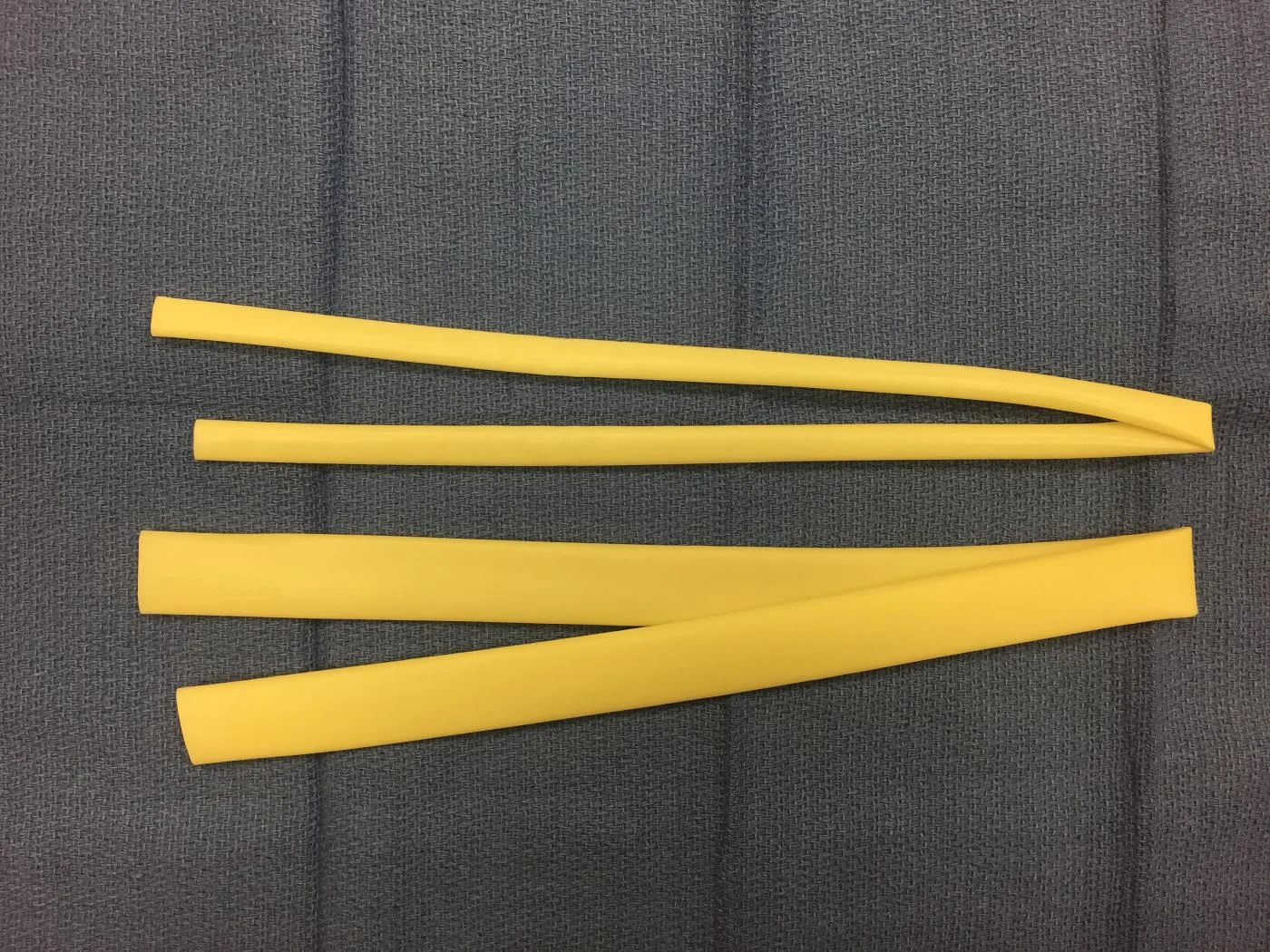

Surgical drains are classified as passive (open) or active (closed) systems. Passive systems use drains (eg, Penrose drains; flexible latex tubing) that rely on gravitational pull, motion, and overflow to facilitate removal of accumulated fluid. These systems are recommended when tissue viability is questionable, exudate is thick (precluding use of a drain with smaller fenestrations), and the location of the wound facilitates gravitational drainage. Use of passive drains is contraindicated for wounds involving the abdominal or thoracic cavity because the drains may create a pneumothorax or pneumoperitoneum and predispose the patient to ascending infection. Passive systems have been associated with more surgical site infections, as compared with active systems.3

Active systems use fenestrated drains (eg, red rubber, silicone) that are attached to a negative-pressure source. These systems can be beneficial in reducing skin maceration and are associated with a lower rate of infection than passive systems are.4 Active systems allow easy monitoring of fluid drainage, which facilitates determining appropriate and timely drain removal. At University of Tennessee, the authors use an active system when a wound pocket can be closed (ie, airtight seal can be created), fluid viscosity is low to moderate, tissue adhesion is highly desired, or the wound does not facilitate open drainage (eg, dorsally located injuries that inhibit ventral drainage, deep wounds). Active systems must be used in body cavities when drainage is required.

Both active and passive systems can achieve drainage goals of wound management as long as basic principles have been followed:1

The size and number of drains have been kept to a minimum to promote effective fluid removal.

The most flexible material has been selected to promote reduced tissue trauma and allow radiographic visualization (ie, radiopacity) should the drain be damaged or dislodged.

To minimize the risk for infection, active (closed) suction drains have been used when possible.

Drains have been removed as soon as possible to lessen likelihood of ascending infection.

Aseptic technique has been applied.

Related Article: Basic Wound Care

Penrose drains, most often used in patients with trauma-induced injury, also can be useful following planned surgeries. In a study evaluating drain placement after intermuscular lipoma removal, 0 of 5 dogs with a Penrose drain developed a seroma, whereas 4 of 6 without Penrose drain placement developed a seroma.5

Penrose drains are available in width increments of one-eighth inch, ranging from one-quarter to 1 inch. Although no veterinary sizing guidelines have been published, the amount of fluid flow is proportional to the drain diameter. At University of Tennessee, if the wound is expected to be highly effusive and passive drainage is preferred, an increased diameter drain may be indicated or multiple small drains (one-quarter inch) can be placed into a very large wound.