Pulmonary Thromboembolism

Anthony Johnson, DVM, DACVECC, Veterinary Information Network

Profile

Definition

Pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE) refers to a blood clot.

Incidence and prevalence are unknown.1

A secondary complication of a primary condition resulting in thrombus formation and blood flow obstruction in the pulmonary vasculature (see Diseases & Risk Factors Associated with PTE)

Pulmonary embolism may be caused by fat accumulation, parasite (eg, Dirofilaria immitis) infiltration, septic emboli, foreign bodies, or air bubbles.

Related Article: Feline Aortic Thromboembolism

Signalment

PTE is almost always secondary to a primary disease, so no specific patient profile exists; however, older patients may be at increased risk for conditions that promote thrombus formation.

TABLE 1: DISEASES & RISK FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH PTE

PTE = pulmonary thromboembolism

Causes

PTE can be caused by any disease that results in a procoagulable state, blood stasis, or endothelial damage.

These factors that contribute to thrombosis are collectively known as Virchow’s triad.

Additional factors can include:

Activation of platelets

Loss of anticoagulant proteins

Increase in procoagulant clotting factors

Older patients may be at increased risk for conditions that promote thrombus formation.

Risk Factors

Any disease causing systemic inflammation can lead to PTE formation.

Related Article: Fatal Air Embolism in an Adult Cat

Pathophysiology

Two general categories of PTE

Those related to D immitis infection (ie, highly inflammatory, producing radiographic changes)

Those related to another underlying disease (can be radiographically subtle)

Thrombi related to D immitis are generally produced in the heart and pulmonary artery.

Thrombi related to other underlying disease may form distally and travel through the right side of the heart, lodging in the pulmonary artery.

When the thrombus enters pulmonary circulation, it obstructs blood flow and causes underperfused (but still ventilated) alveoli.

This results in ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) mismatch.

Response to the thrombus produces additional pathology (eg, pulmonary edema, atelectasis, pleural effusion through inflammatory cytokine release).

Small thrombi are clinically silent,as pulmonary circulation can bypass the affected region through intrapulmonary shunting.

Larger thrombi can cause sudden death.

In humans with signs of PTE, typically >40% of the vascular bed is obstructed.

Other factors affecting clinical severity include:

Severity of underlying disease

Concurrent cardiac disease

Degree of secondary response (eg, edema, bronchoconstriction, atelectasis)

History, Examination, & Signs

History may include glucocorticoid use, neoplasia, cardiac disease, recent surgery, or immobilization.

Physical examination findings may include tachypnea, cyanosis, pallor, and jugular venous distention.

Clinical findings of underlying disease may also be present.

Recognition of PTE can be challenging, as affected patients may appear clinically healthy or markedly hypoxic.

Depending on degree of hypoxia, affected patients may show tachypnea, labored breathing, cough or hemoptysis, sudden collapse, or altered mentation.

Thoracic auscultation may disclose a split S2 caused by pulmonary hypertension.

Related Article: Acute Pelvic Limb Paresis & Respiratory Effort in a Cat

Diagnosis

Differentials

Differential diagnoses for patients with acute hypoxia and labored breathing include:

Upper airway obstruction

Pneumonia

Inhaled toxins

Pulmonary hemorrhage

Asthma

Pleural space disease

Congestive heart failure

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

A-a Gradient

Formula for alveolar and arterial gradient: (A-a) gradient = PaO2 – PaO2

PaO2 obtained from arterial blood gas

Simplified PAO2 for patients breathing room air at sea level: PAO2 = 150 mm Hg – (PaCO2 / 0.8)

Normal is 10–15 mm Hg

Elevated in cases of diffusion impairment (eg, PTE, pulmonary edema)

Corrects for hypoxia from hypoventilation and elevated alveolar CO2

Valid only in patients that are breathing room air

Definitive

Definitive diagnosis is challenging and often established after necropsy.

PTE should be considered in any patient with acute tachypnea, hypoxia, and labored breathing with history of underlying disease.

PTE should be considered in any markedly hypoxic patient with normal or near-normal findings on radiography.

Any disease causing systemic inflammation can lead to PTE formation.

Laboratory Findings

CBC, serum chemistry panel, and urinalysis results are variable and nonspecific and may reflect underlying condition.

Stress leukogram may be present.

Arterial blood gas analysis

Hypoxia (PaO2 <60 mm Hg), elevated A-a gradient (see A-a Gradient), and decreased P:F ratio (see P:F Ratio).

Hypocapnia (PaCO2 <40 mm Hg) and respiratory alkalosis may be present.

Severely affected animals may progress to respiratory acidosis.

On echocardiography, signs of right-sided volume overload or pulmonary arterial dilation may be present.

Rarely, the thrombus itself may be visible.

Presence of D immitis may be noted.

Normal results on echocardiogram do not rule out PTE.

Helical or spiral CT scan may show the thrombus and should be considered if available and if patient can withstand anesthesia.

Pulmonary angiography may be selective (eg, catheter directed and limited to pulmonary artery) or nonselective (eg, administered intravenously) and may demonstrate the thrombus and a filling defect.

Dilution of contrast material makes nonselective angiography less accurate, but this procedure is commonly available and safer.

V/Q perfusion scan/nuclear scintigraphy may be accurate but is not widely available.

Scans are highly sensitive for PTE but not specific.

P:F Ratio

Calculated by dividing the PaO2 by the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) as a decimal

Benchmarks lung function against various levels of supplemental oxygen

Normal P:F ratio is approximately 500.

<300 indicates acute lung injury or moderate respiratory dysfunction

<200 indicates severe respiratory failure

A-a = alveolar and arterial, ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome, PaCO2 = partial pressure arterial carbon dioxide, PaO2 = partial pressure arterial oxygen, PaO2 = partial pressure alveolar oxygen, P:F = ratio of arterial oxygen concentration to fraction of inspired oxygen, PTE = pulmonary thromboembolism, V/Q = ventilation/perfusion

Lateral (A) and VD (B) views of a patient with heartworm disease and PTE. Note blunting and enlargement of the pulmonary arteries and the heavy interstitial to alveolar infiltrate.

Imaging

In patients with PTE caused by heartworms, thoracic radiography may show signs of blunting and enlarged pulmonary arteries, plus interstitial to alveolar infiltrate (Figure 1).

In patients with PTE secondary to other underlying disease, radiographs may appear normal.

Additional findings may include:

Right-sided heart changes from D immitis infection or pulmonary hypertension

Areas of lucency and decreased perfusion caused by reduction of pulmonary blood volume

Pleural effusion

Interstitial or alveolar infiltrate

Other Diagnostics

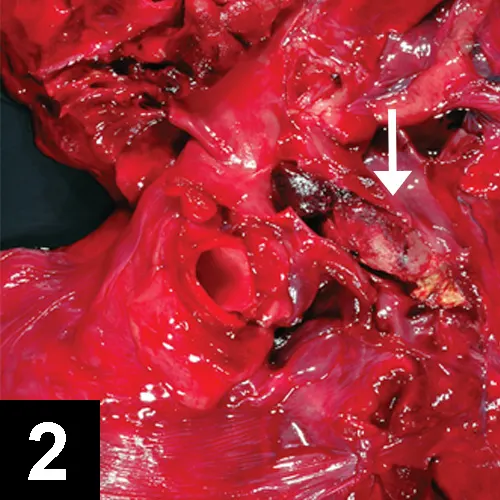

Thrombus (arrow) in pulmonary artery

D-Dimer testing measures fibrin cross-linked in a thrombus and then degraded.

Measurement is more specific than fibrin degradation product (FDP) but still subject to false-positive and negative results.

Coagulation assays (PT/PTT) have limited use.

Results less than reference intervals do not indicate a prothrombotic tendency.

Thromboelastography (TEG) may show hypercoagulable state but is not confirmatory or predictive of PTE.

Postmortem findings may show in situ thrombus (Figure 2).

Treatment

Inpatient & Surgical

Treatment is designed to provide comfort, improve oxygenation, reverse prothrombotic state, and address underlying disease.

For patients with hypoxia and respiratory distress, in-patient therapy is strongly recommended.

Surgery includes cardiopulmonary bypass (generally unavailable).

Activity

Severe activity restriction for hypoxic patients is indicated.

Limited activity should be encouraged for at-risk patients, if feasible.

For conditions associated with PTE, the client should be informed that PTE is possible and diagnosis and management may be problematic.

This is of particular importance for patients with immune-mediated hemolytic anemia (IMHA), hyperadrenocorticism, or dirofilariasis caused by the prevalence of these conditions.

Medications

Although many therapeutic options exist for anticoagulation and thromboprophylaxis in humans, few have proven efficacy in veterinary medicine in randomized, controlled trials.

No clear drug regimen has emerged as superior for either prevention or management of PTE (except aspirin use in patients with IMHA).1

Fluids

Fluid deficits and daily maintenance requirements should be met unless contraindicated.

Volume overload and right-sided congestive heart failure are possible; careful monitoring of volume status is imperative.

Anticoagulants

Heparin and warfarin are indicated to prevent clot growth but do not cause clot lysis.

Controversy exists regarding unfractionated versus low–molecular–weight heparin.

Monitoring of clotting times is indicated.

Unfractionated heparin

200–400 U/kg SC q6–8h

80–100 U/kg IV, then CRI at 18 U/kg/hr

Warfarin

0.1–0.22 mg/kg PO q24h

Warfarin is highly protein-bound and interacts with numerous other drugs.

Thrombolytics

Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and streptokinase can cause clot lysis.

Risk for bleeding, lack of data, regimen complexity, and expense must be considered.

Dosing for tPA

Dogs: 1 mg/kg IV over 15 min q60–80min until response is noted; repeat as needed

Cats: 0.1–1 mg/kg/hr for total dose of 1–10 mg/kg

Dosing for streptokinase

Dogs: 90,000 IU IV (over 30–60 min) loading dose, then 45,000 IU/hr IV CRI2

Cats: 90,000 U over 20–30 min, then 45,000 U/hr until resolution

Use caution: High mortality associated with this dosing regimen.

Antiplatelet Drugs

Aspirin (low dose)

Dogs: 0.5 mg/kg PO q24h

Cats: 5 mg/cat PO q72h

Clopidogrel

Dogs: 0.5 mg/kg PO q24h with aspirin

1 mg/kg PO q24h alone

Cats: 18.75 mg PO q24h

Oxygen Therapy

SpO2 >90% and PaO2 >60 mm Hg should be maintained.

Patients with severe alterations of ventilation (PaCO2 >60 mm Hg) or oxygenation (SpO2 <90%) despite oxygen therapy often require mechanical ventilation.

Prognosis is poor.

Sedation & Analgesia

Cautious analgesia or sedation may be indicated.

Close monitoring is needed, but antianxiety medications may improve respiratory status.

Patients that are already bleeding or have prolonged clotting times should not receive anticoagulants or undergo invasive procedures.

Follow-up

Patient Monitoring

ICU-level, 24-hour care (including respiratory monitoring) is required.

Calculation of P:F may help assess degree of oxygenation improvement.

If patient receives anticoagulants, monitor PT/PTT, TEG, and heparin anti-Xa levels.

Patients receiving warfarin or heparin should have dose adjusted to achieve 1.5–2x the high-end of normal range of the PTT or the baseline value.

International normalized ratio may provide more accurate coagulation information than PT/PTT.

This is rarely used in veterinary medicine.

Complications

With anticoagulants or thrombolytics: sudden death, hypoxia, cardiac dysrhythmias, pneumothorax, and hemorrhage possible

At-home Treatment

Supportive care and therapy specific to the primary disease

Future Follow-up

For patients with some predisposing diseases (eg, IMHA), low-dose aspirin should be administered unless contraindicated.

Warfarin, heparin, or other antiplatelet drugs (eg, clopidogrel) may be considered based on underlying disease.

Availability of helical CT and selective angiography, improvements in antemortem testing, and studies designed to identify the best agents for thromboprophylaxis and PTE therapy may help improve diagnosis and management of patients.

In General

Relative Cost

Therapy: $$$–$$$$$

Cost Key

$ = up to $100

$$ = $101–$250

$$$ = $251–$500

$$$$ = $501–$1000

$$$$$ = more than $1000

Prognosis

Prognosis depends on the underlying disease and degree of hypoxia.

Generally fair to poor unless underlying process reversible.

Euthanasia is reasonable for severely affected patients and those with irreversible diseases.

FDP = fibrin degradation product, IMHA = immune-mediated hemolytic anemia, PaCO2 = partial pressure arterial carbon dioxide, PaO2 = partial pressure arterial oxygen, P:F = ratio of arterial oxygen concentration to fraction of inspired oxygen, PT = prothrombin time, PTE = pulmonary thromboembolism, PTT = partial thromboplastin time, SpO2 = peripheral capillary oxygen saturation, TEG = thromboelastography, tPA = tissue plasminogen activator