Primary Hypoparathyroidism

PROFILE

As with primary hyperparathyroidism (see companion article Primary Hyperparathyroidism), primary hypoparathyroidism is one of the most common primary parathyroid gland diseases with excellent prognosis.

Definition & Pathophysiology

Primary hypoparathyroidism, the absence or destruction of parathyroid tissue, causes a deficiency in parathyroid hormone (PTH).

This can lead to marked hypocalcemia.

Most commonly refers to immune-mediated parathyroid destruction

Other causes may include parathyroid gland damage or removal following thyroidectomy, parathyroid gland damage by another disease in the neck, or following sudden correction of hypercalcemia (eg, treatment of primary hyperparathyroidism).

Related Article: Anesthesia for Parathyroid Disease

Systems

Neuromuscular signs are most common.

Cardiac and GI signs may be present.

Incidence & Prevalence

Reasonably rare

Reports include two case series of fewer than 30 dogs and many individual reports.1,2

SignalmentSpecies & Age Range

Primarily reported in young to early middle-aged dogs and cats but can affect juvenile and geriatric patients

Sex Predilection

Female dogs are overrepresented.

History

Presenting signs may be chronic or appear acutely following excitement or exercise.

Physical Examination

Potential findings:

Seizures during examination

Episodes of tetany

Behavioral disturbances

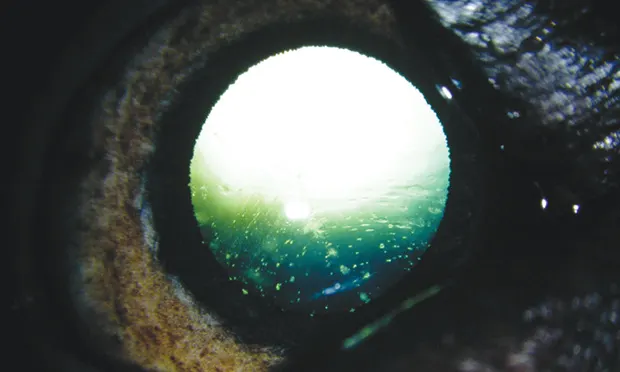

Cataracts (Figure 1)

Low or decreased body condition score

Third eyelid protrusion (cats only)3

Bradycardia

Figure 1. Hypocalcemic cataract in a dog with primary hypoparathyroidism (Courtesy Stuart Ellis, BVSc, CertVOphthal, MRCVS)

Clinical Signs

Signs are predominantly neuromuscular because of increased neuromuscular tissue excitability secondary to hypocalcemia.

Approximate frequency of clinical signs1,2:

Seizures (65%–75%)

Muscle tremors and cramping (55%–65%)

Stiff gait and/or lameness (45%–65%)

Behavioral changes (50%; eg, aggression, restlessness, hypersensitivity, disorientation)

Hyperthermia (35%)

Panting (35%)

Facial pruritus (25%)

GI signs (12%–35%; eg, inappetence, weight loss, diarrhea, vomiting)

DIAGNOSIS

Definitive

Undetectable or barely detectable plasma PTH concentration in a patient with marked hypocalcemia

Differential

The differential diagnoses for hypocalcemia can vary (see Table in Primary Hyperparathyroidism).

Immune-mediated primary hypoparathyroidism is the most likely differential with marked clinical hypocalcemia and no history of recent parturition, neck trauma, or surgery.

Laboratory Findings

Chemistry panel (total hypocalcemia, possible hyperphosphatemia and hypomagnesemia, ionized hypocalcemia)

Other Diagnostics

Plasma PTH concentration is usually reported as barely detectable to undetectable.

ECG may rarely reveal bradycardia and prolongation of the ST segment.

TREATMENT4

Surgical

Surgical treatment is not possible.

Medical

Emergency treatment of clinical hypocalcemia (see Prevention & Treatment of Hypocalcemia in Primary Hyperparathyroidism)

Therapy with oral vitamin D, calcium, and calcium gluconate infusion should be initiated via IV infusion as soon as possible.

Calcium gluconate infusion should continue until a total serum calcium concentration can be maintained at low-normal concentration with PO therapy only.

Total and ionized calcium concentrations should be measured q12–24h while tapering infusion.

Hypomagnesemia may cause poor response and require supplementation.

Excessive vitamin D supplementation may cause hypercalcemia and renal injury.

Follow-up

Serum calcium concentrations should be reexamined and measured at least twice weekly for the first 2–3 weeks after discharge, then q1–3mo.

Vitamin D dosing should be adjusted to maintain low-normal total calcium concentration.

Lifelong vitamin D therapy is required.

Calcium treatment is often tapered and stopped after 2–4 months.

IN GENERAL

Relative Cost

Initial stabilization may be costly. Lifelong therapy: $$$$$

Prognosis

Excellent with lifelong PO therapy if the patient is monitored carefully and initial stabilization is successful