An Overview of Feline Lymphoma: GI & Beyond

Craig A. Clifford, DVM, MS, DACVIM (Oncology), BluePearl Pet Hospital, Malvern, Pennsylvania

Christine Mullin, VMD, DACVIM (Oncology), BluePearl Pet Hospital, Malvern, Pennsylvania

Profile

Definition

Lymphoma (LSA) is one of the most commonly occurring neoplasms in cats.

Characterized by abnormal proliferation of a monoclonal (or, rarely, biclonal) population of malignant lymphocytes.

Systems

The most commonly affected system is the GI tract.1-4

Other presentations (eg, nasal, mediastinal, laryngeal, tracheal, renal, CNS, cutaneous, peripheral nodal involvement) are possible.<sup1-4 sup>

Incidence & Prevalence

Hematopoietic neoplasia accounts for about 30% of all feline cancers.1

LSA comprises approximately 50%-90% of tumors within that category.<sup1 sup>

Risk Factors

FeLV

Implementation of viral screening and vaccination programs has caused a dramatic decline in FeLV-associated LSA.1

FIV

Unlike FeLV, FIV does not lead directly to LSA.1

FIV immunosuppressive effects can be an indirect cause of LSA in FIV-positive cats, for which there is over a 5-fold increase in LSA development risk.1

Inflammation

Given the frequent association between inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and GI LSA, a role for inflammation in the development of this cancer has been postulated.1,5-7

Immunosuppression

A predisposition for the development of LSA in cats undergoing potent immunosuppressive therapy following renal transplants has been reported.1

Signalment

Breed Predilection

An overrepresentation of Siamese cats has been reported, but any breed can develop LSA.1

Age

All presentations: Median, 11 years1-4

Mediastinal presentations (often FeLV-associated): Median, 2-4 years1,4

Sex

A male predisposition has been reported.1-4

Pathophysiology

The pathologic consequences of LSA depend on the organ system(s) involved, cytologic or histologic characteristics, and immunophenotypic (B-cell, T-cell, NK [natural killer] cell) classification.1,4,7-9

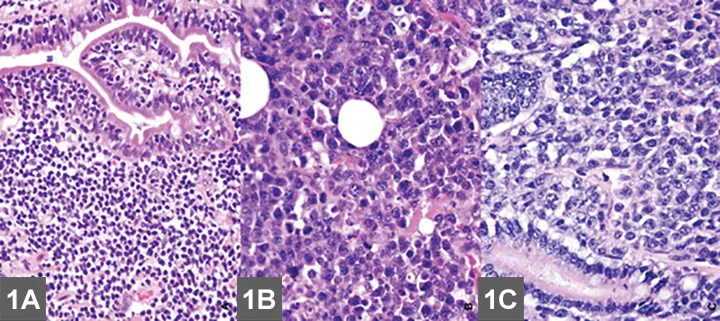

EATL type II (small cell) is the most common intestinal LSA in cats (A) and requires immunohistochemical labeling for proper phenotypic characterization and often PARR testing to differentiate from IBD. (B) EATL type I (large cell) occurs less commonly in the small intestine of cats, and neoplastic cells are often large granular lymphocytes. (C) Diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCL) occur most commonly in the stomach of cats or may present as part of multicentric disease. Although LSA diagnosis is usually made with routine microscopic examination, immunohistochemistry is required to accurately differentiate EATL type I from DLBCL (magnification 40×). Image and description courtesy of Matti Kiupel, Dr. vet. med. Habil, MS, PhD, DACVP, Michigan State University.

Gastrointestinal

There are 2 main forms of GI LSA.

Enteropathy-associated T-cell LSA (EATL) type I (high-grade or large cell/lymphoblastic GI LSA)1,6-7

Typically involves more intermediate to large cells that display transmural invasion and often form masses (Figure 1B).

Intermediate to large B-cell LSAs, including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), also occur with slightly less frequency (Figure 1C).

Cats are often presented with a palpable mass and more acute and severe clinical signs.1

Large granular LSA (LGL)—an aggressive subtype of EATL type I—is comprised of either cytotoxic T-cells or NK cells and characterized by multiple masses within the GI tract and other organ systems.8

EATL type II

The more common presentation of GI LSA characterized by diffuse superficial (mucosal/lamina propria) infiltration of small T-lymphocytes that often display epitheliotropism (Figure 1A).1,5-7

Referred to as low-grade, lymphocytic, small cell, or indolent GI LSA, and associated with a slowly progressive disease course.1,5-7

Extension of disease into regional lymph nodes, liver, spleen, blood and, less commonly, the kidneys can also be seen with both forms of GI LSA.1

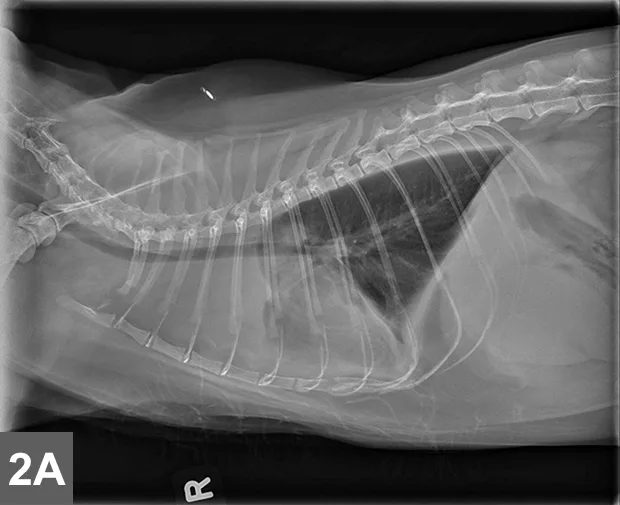

Cranial mediastinal mass in a cat. Note the increased opacity of the entire cranial mediastinum with border effacement of the cranial margin of the heart and dorsal deviation of the trachea in the lateral view.

Mediastinal

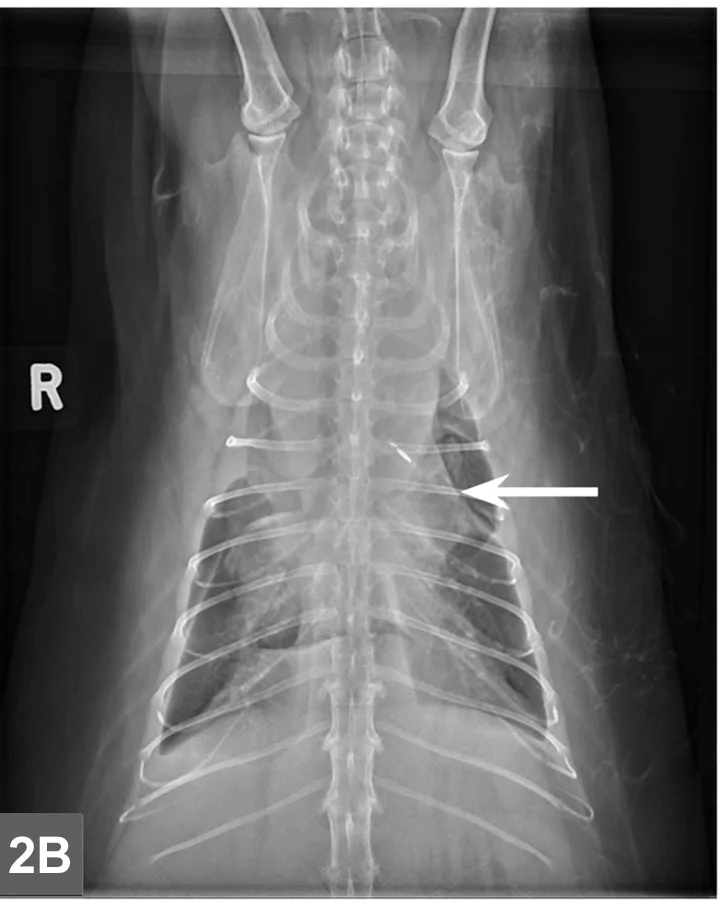

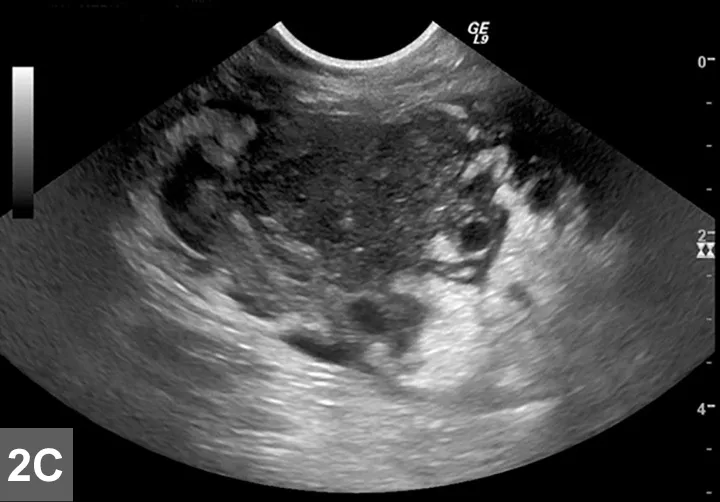

Typically localized form of LSA involves infiltration of the thymus and/or cranial mediastinal and sternal lymph nodes with intermediate to large neoplastic lymphocytes with signs related to the intrathoracic mass effect and secondary pleural effusion (Figure 2).

Cranial mediastinal mass in a cat. There is also widening of the cranial mediastinum with rounded margins and border effacement of the cranial margin of the heart in the VD view. Pleural effusion contributes to effacement of the cardiac silhouette and to the widened appearance of the cranial mediastinum in the VD view (arrow).

Extranodal

Nasal

Most common form of extranodal LSA.1,9

Characterized by diffuse infiltration or a mass effect within the nasal cavity, sinuses, and often the nasopharynx, leading to chronic upper respiratory signs.1,9

Up to 20% of cats with nasal LSA will have systemic involvement.1,9

Laryngeal & tracheal

Uncommon and typically localized form seen more often in older cats; can lead to signs of upper airway noise and obstruction.

Cranial mediastinal mass in a cat.Thoracic ultrasound demonstrates an irregularly marginated, hypoechoic mass within the cranial mediastinum surrounded by a small-volume pleural effusion within the left and right hemithoraces (ventral to the left in image). Image and description courtesy of Christopher T. Ryan, VMD, DABVP, DACVR, Hope Veterinary Specialists.

Renal

Typically aggressive form of feline LSA characterized by diffuse to nodular infiltration, usually of both kidneys, often leading to azotemia and acute illness.1,3,10

There is a 40%-50% risk of CNS involvement.1

CNS

Comprises up to one-third of all intracranial tumors and can be either solitary, multifocal, or diffuse, affecting the brain and/or spinal cord.

A considerable percentage (up to 80%) will also have extra-CNS disease.1

Cutaneous

Typically characterized by an indolent disease course and can be localized or consist of multifocal skin lesions, usually composed of epitheliotropic T-lymphocytes.1

Peripheral nodal

Can be part of a multifocal presentation of high-grade LSA or serve as the primary site of disease, although it is an uncommon form.

Another rare form of nodal LSA has been reported and is similar clinically and histologically to Hodgkin Lymphoma in humans.1,11

This form is most commonly characterized by enlargement of 1 lymph node or chain of lymph nodes, often in the cervical region, and typically displays a more indolent disease course.1,11

History, Signs, & Examination

GI

Weight loss

Anorexia

Vomiting

Diarrhea

Palpable intestinal thickening or mass effect(s)

Cachexia

Dehydration

Mediastinal

Tachypnea

Dyspnea

Anorexia

Weight loss

Muffled heart and lung sounds

Horner syndrome

Extranodal

Nasal

Nasal congestion

Sneezing

Epistaxis

Facial deformity

Ocular discharge

Decreased ocular retropulsion

Laryngeal & tracheal

Stridor

Voice change

Gagging

Renal

Weight loss

Anorexia

Vomiting

Polyuria/polydipsia

Palpable renomegaly

CNS

Seizures

Abnormal mentation

Cranial nerve deficits

Paresis or paralysis

Cutaneous

Slowly progressive, erythematous, plaque-like, crusted, and occasionally pruritic solitary or multifocal dermal lesions, often on the head or face

Peripheral Nodal

Enlargement of a single lymph node or lymph node chain (Hodgkin-like) or generalized peripheral lymphadenomegaly

Diagnosis

Definitive Diagnosis

Workup should consist of full staging with CBC, serum chemistry panel, FeLV/FIV testing, urinalysis, abdominal ultrasound, and thoracic radiographs.

Advanced imaging may be indicated for nasal or CNS presentations of LSA (see Imaging).

Cytology

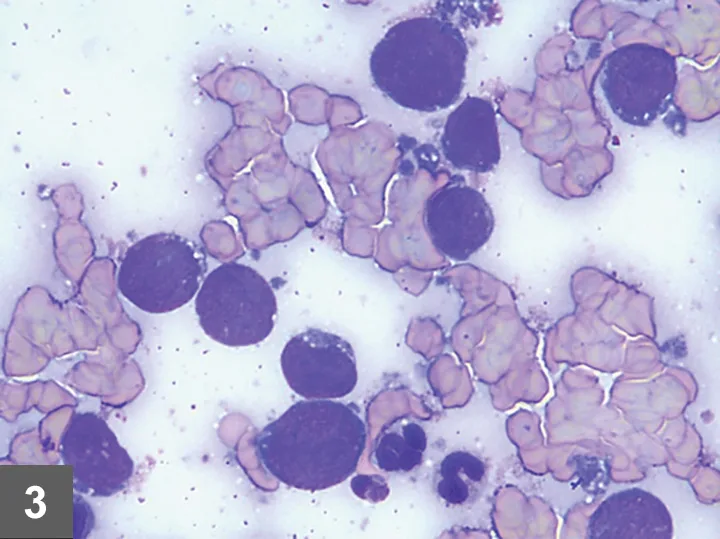

Fine-needle aspirate (FNA) cytology of masses and/or involved organs is often adequate to provide a definitive diagnosis of intermediate to high-grade LSA and LGL (Figures 3-5, see gallery).1,8

Cytological assessment alone is often not sufficient for diagnosis of EATL type II and other indolent forms.1,5-6

Histopathology is needed for a definitive diagnosis of EATL type II or in cases in which cytology is equivocal or affected tissue is not accessible via FNA.1,5-7

FIGURE 3

Several large lymphocytes with a large round nucleus with finely stippled chromatin and a scant amount of basophilic cytoplasm that commonly contains few to many small, punctate, clear vacuoles. These vacuoles are also commonly found in the cytoplasmic fragments (lymphoglandular bodies) (magnification 1000×). Image and description courtesy of Casey J. LeBlanc, DVM, PhD, DACVP, KDL VetPath.

Histopathology

EATL type I is typically a straightforward histologic diagnosis.1,5-7

EATL type II can be more difficult to confirm; it must be histologically differentiated from IBD (Figure 6, see gallery).1,5-7

Characteristics more suggestive of EATL II over IBD include the presence of lymphoid infiltration beyond the mucosal layer, the presence of epitheliotropism, and certain characteristics of neoplastic lymphocytes.1,5-7

Distinction can still be difficult without more advanced histologic techniques (see Table); how the biopsy is obtained is controversial.1,5-7

Histologic Sampling Options

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) & Clonality Assay (PARR)

Additional testing is necessary if diagnosis is equivocal after histological assessment.

IHC identifies the neoplastic lymphocytes as T-cell or B-cell by staining for cell surface markers and can help differentiate IBD from EATL type II (Figure 8, see gallery).1,5-7

PARR analysis confirms clonality, the hallmark of malignancy.1,5-7

A recent study evaluating IHC and PARR noted that even though histopathology is highly specific for diagnosing feline GI LSA, sensitivity was enhanced by the addition of IHC and further improved by PARR.1,5-7

Laboratory Findings

GI

Anemia

Hypoalbuminemia

Hypocobalaminemia

Renal

Azotemia

Anemia

Nasal, Laryngeal & Tracheal, CNS, Cutaneous, Mediastinal, Peripheral Nodal

Anemia

Neutrophilia

Often normal

Imaging

GI

EATL type I

Abdominal ultrasound often reveals a mass or masses within the GI tract, regional lymphadenopathy, and sometimes masses within, or infiltration of, other extra-GI organs (liver, spleen, kidneys).

EATL type II

The majority with this form of LSA will have small intestinal wall thickening.

Mild regional lymphadenomegaly is also commonly seen.

Mild, non-specific changes may also be noted in the liver and spleen.

Mediastinal

Thoracic radiographs may reveal a mediastinal mass effect.1-4

Ultrasound can be used to visualize the cranial mediastinum and may reveal a hypoechoic mass or cluster of enlarged lymph nodes (Figure 5, see gallery).

Extranodal

Nasal

Advanced imaging (CT, MRI) is needed to determine extent of infiltration in the nasal cavity, sinuses, nasopharynx, and retrobulbar space.

Can often reveal bony lysis.

Images can be used for radiation therapy planning.

Laryngeal & tracheal

Cervical radiographs may reveal a narrowing of the airway lumen

These are not sensitive for detection of a mass, which may require sedated airway examination or advanced imaging.

Renal

Abdominal ultrasound is the imaging modality of choice for renal LSA.

This confirms bilateral renomegaly, often with nodular to diffuse cortical changes and subcapsular thickening or fluid.

CNS

MRI is ideal and may reveal intra- or extradural spinal cord masses and/or focal, multifocal, or diffuse contrast-enhancing lesions in the brain.

Treatment

Inpatient or Outpatient

Most cats with LSA are treated on an outpatient basis.

Some patients presented in respiratory distress (mediastinal) or with dehydration or hypovolemia from severe acute or protracted GI distress may require short-term hospitalization during or before initiation of chemotherapy.

Medical Therapies

Systemic

Chemotherapy indicated for multicentric or nonresectable disease.

Chemotherapy protocols vary depending on disease severity (eg, type and grade, comorbidities, owner finances, logistics).

Local Therapies

Surgical

Some presentations, especially those involving localized disease (some GI, CNS, cutaneous, Hodgkin-like peripheral nodal), can be treated with surgery in lieu of, before, or in combination with systemic therapy.

Because of a lack of data in veterinary literature, there is some debate regarding the role of surgery in the treatment of intermediate- to high-grade GI LSA.1

Radiotherapy

Reserved for localized presentations of LSA (some CNS, Hodgkin-like peripheral nodal, laryngeal/tracheal, some cutaneous) and is the treatment of choice for nasal LSA.1,9

There have been interesting results reported on the use of radiotherapy for cats with GI LSA.1,9

Radiotherapy can also be considered as a rescue therapy for cats with mediastinal LSA.1,9

Medications

Chemotherapy & Corticosteroids

Intermediate- to high-grade forms:

The treatment of choice for feline LSA is combination (CHOP-based) chemotherapy consisting of weekly to biweekly administration of a rotating schedule of vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and occasionally l-asparaginase, with daily corticosteroids (prednisolone, methylprednisolone), typically given for 19-25 weeks.1

When renal or CNS involvement is present or suspected, the authors often incorporate agents that cross the blood-brain barrier (eg, lomustine, cytarabine).1

Second-line protocols typically involve lomustine, chlormethine, procarbazine, cytarabine, dactinomycin, melphalan, and others.1,2

EATL type II

First-line protocols often involve the chronic administration of daily steroids and chlorambucil, which can be given on an every-other-day schedule or as higher pulse doses once every 2-3 weeks.1,5

The authors prefer the chronic low-dose protocol.

Second-line protocols typically involve the use of other alkylators (eg, cyclophosphamide, lomustine), although high-dose chemotherapy protocols more typically used for intermediate- to high-grade LSA can be considered for severe or refractory EATL type II cases.1,5

The most commonly used second- line protocol consists of biweekly high-dose cyclophosphamide and has been associated with a high response rate and relatively long remission duration for cats that no longer respond to chlorambucil.1,11

Similar protocols can be considered for patients with indolent non-GI forms of LSA, such as cutaneous or Hodgkin-like peripheral nodal presentations.1,11

Adverse Effects

Quality of life during chemotherapy is generally good to excellent.

Adverse effects commonly associated with high-dose chemotherapy involve mild-to-moderate transient GI upset (eg, anorexia, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation).

Cats have an extremely low chance of secondary infection related to bone marrow suppression (febrile neutropenia).1

Alopecia is uncommon, but cats may lose their whiskers.1

Chlorambucil side effects include mild GI disturbances, myelosuppression (particularly thrombocytopenia), and increased liver enzymes.1,5

Contraindications & Precautions

Doxorubicin may lead to worsening renal disease in cats with pre-existing kidney insufficiency and thus should be avoided in these patients.

Steroids should be used judiciously in patients with pre-existing cardiac disease, diabetes mellitus, and renal disease.

Nutrition

Given the evidence for the role of inflammation and concurrent IBD in cats with EATL type II, transition to a novel protein diet and supplementation with probiotics and vitamin B12 can be advantageous ancillary therapies with this subtype of LSA.1,6,7

Follow-up

Follow-up hospital visits are dependent on patient status and protocol implemented.

Patients receiving standard chemotherapy protocols often have a weekly to biweekly schedule for examination, blood work, and treatment.

Traditional protocols for high-grade LSA are 19-25 weeks with monthly rechecks thereafter.1,4

Cats receiving low-dose chemotherapy for EATL type II are evaluated on a monthly to bimonthly basis.

Imaging may be repeated at specific time intervals to monitor and confirm remission status.

In General

Prognosis

Long-term prognosis associated with feline LSA is extremely variable and highly dependent on anatomic location, therapy pursued, and response to therapy.

GI Considerations

EATL type I: The reported response rate to multi-agent chemotherapy ranges from about 50%-75% for a median remission duration and expected survival of approximately 4-6 and 6-8 months, respectively.1,2,5

Recent data suggest that a small (~15%-25%) portion of cats will have survival of 1-2 years.2,5

The LGL form carries a poor prognosis of <60 days survival even when treated with standard chemotherapy protocols.9

EATL type II: Remission is generally defined as improvement or resolution of clinical signs, and the summary of several studies suggest that 70%-85% will respond for a median survival time of >2 years.6

Mediastinal

FeLV-associated disease is linked to short (~3 months) survival even with treatment, whereas the general cat population will typically experience a high (70%-90%) response rate for a median survival time of 9-12 months.1-5

Extranodal

Nasal

Cats with nasal LSA that are treated with radiotherapy (± chemotherapy) typically experience high response rates, (>90%) and one study documented 2-3 year survival times.10

Laryngeal/tracheal

Although the response rate was high for 1 small study of cats with this presentation, the median survival time was <6 months.1,3

Renal

This form of LSA generally carries a poor prognosis with a median survival time of 3 months for all cats.

Cats experiencing a complete response to therapy (~60%) had survival times of ~6 months in one study.3

CNS

The prognosis for cats with CNS LSA is typically poor to grave with a reported median survival time of 70 days.3

Cutaneous

There are essentially no reliable data evaluating the response rate and survival associated with treatment for feline cutaneous LSA.

Peripheral nodal

The prognosis for cats with high-grade or multicentric peripheral nodal LSA is similar to that of other high-grade forms of the disease.

Localized Hodgkin-like form of disease can be associated with longer survival times with effective treatment.1,11

Relative Cost

$$$$$

CNS = central nervous system, DLBCL = diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, EATL = enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma, FNA = fine-needle aspirate, IBD = inflammatory bowel disease, LGL = large granular LSA, LSA = lymphoma, PARR = PCR antigen receptor gene rearrangement, PCR = polymerase chain reaction

Editor's note: This article was originally published in July 2015 as "Feline Lymphoma"