Endourology: A New Way of Looking at Things

Interventional Endoscopy & Endourology: Part 2This is the second of a 2-part series. Read part 1, Interventional Endoscopy: The Essentials.

Some of the most common interventional endoscopy techniques performed in veterinary medicine today involve the urinary tract.

Urinary Interventions

Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy

This procedure is rarely necessary, as less than 10% of all nephroliths in dogs and cats become a clinical problem. In these patients, careful monitoring is the most appropriate course of action unless recurrent urinary tract infection, hydronephrosis, worsening renal function, or nonpyelonephritis-associated pain or discomfort occurs. When these situations develop, traditional surgical options (eg, nephrotomy) can be met with complications and long-term morbidity. In a feline study looking at normal cats, a 10% to 20% decrease in glomerular filtration rate was noted in the kidneys that underwent nephrotomy.1

Related Article: Urinary Obstruction - Treatment Measures

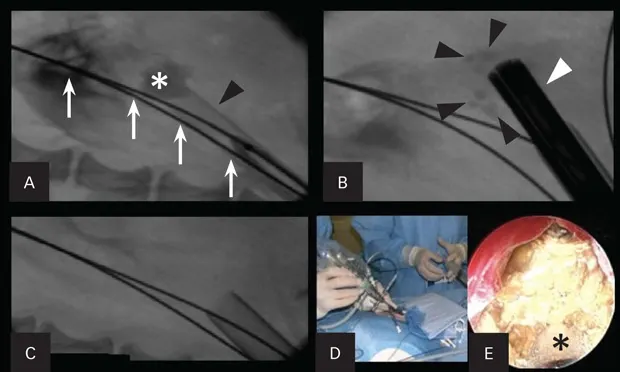

In humans, less invasive methods (eg, extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy) have been shown to dramatically improve the preservation of renal function. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) can be markedly effective in removing all stone fragments in the calices. In addition, PCNL does not cause injury to the nephrons (Figure 1). Instead, the nephrons are spread apart with the use of a balloon dilation kit to allow a scope and intracorporeal lithotrite to remove the stone debris effectively. This has been shown in humans to be highly renal sparing and has been effective in the author’s practice.

Figure 1. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy in a 3.1-kg female Yorkshire terrier with large nephroliths. Use of a percutaneous access kit under fluoroscopic guidance allows visualization of the large nephrolith (asterisk; A). The access sheath (black arrowhead) is inserted through the renal parenchyma over a dilation balloon. Two safety wires (white arrows) are present. The nephroscope (white arrowhead) is inserted through the sheath onto the stone with a lithotrite, breaking the large stone into fragments (black arrowheads; B). Fluoroscopic image after all stone fragments had been removed from the renal pelvis (C). The nephroscope being placed through the access sheath during percutaneous renal access (D). An endoscopic image of the nephrolith taken during lithotripsy (E). The lithotrite (asterisk) is seen through the working channel of the nephroscope.

Ureteral Stenting

Ureteral stenting can divert urine through the ureteral lumen and into the urinary bladder, away from the renal pelvis. It can be a useful technique for treatment of a ureteral obstruction secondary to ureterolithiasis, ureteral or trigonal obstructive neoplasia, and ureteral strictures.

Passive ureteral dilation occurs after stent placement, resulting in dilation of the ureter between 4 and 8 times its normal diameter, which can improve the flow of urine, allow the passage of ureteroliths, or allow the passage of a flexible ureteroscope if necessary. In the author’s practice, ureteral stents (Figure 2) have been placed in more than 300 dogs and cats, with a placement success rate exceeding 95%. It is typically performed endoscopically in dogs and surgically assisted in cats.

Figure 2. Lateral radiograph of a cat with a double pigtail ureteral stent (yellow arrows). The stent is placed next to the large number of ureteroliths (black arrows).

In dogs, ureteral stents are commonly associated with minimal perioperative morbidity and mortality and are a good alternative to the more invasive surgical technique. The long-term complications in cats are dysuria (5%–40%) and need for stent exchange (~20%). The irritation is likely attributable to presence of the distal pigtail of the stent that exits the ureterovesicular junction in the proximal urethra. Dysuria is uncommon after ureteral stenting in dogs. In the author’s practice, ureteral stents have not been used in cats since development of the subcutaneous ureteral bypass (SUB) device.

Subcutaneous Ureteral Bypass Device

The use of SUB devices has become more common. They are typically used in feline patients with ureteral obstructions (Figure 3) and are preferred when compared with ureteral stenting in cats. An indwelling SUB device can be created using a cystostomy catheter and a combination locking-loop nephrostomy catheter. This device was modified after reports in human medicine described a nephrostomy tube that could remain indwelling for longer periods.

Figure 3. Lateral radiograph of a cat with a SUB device. The locking loop pigtail catheter connecting the subcutaneous shunting port is connected to a straight cystostomy catheter, allowing for a ureteral bypass.

The device has a subcutaneous shunting port that can be sampled and flushed as needed. In humans, a similar device has been shown to reduce complications associated with externalized nephrostomy tubes and improve quality of life.2 SUB devices have been placed in more than 150 feline and canine patients in the author’s practice with favorable results and are now the preferred treatment for feline ureteral obstructions. In dogs, the device is reserved for when stent placement fails. The perioperative complication rate associated with SUB devices has declined with the development of a commercially available device (<10%).

Related Article: Interventional Endoscopy - The Essentials

Cystoscopic-Guided Laser Ablation of Ectopic Ureters

In dogs, ectopic ureters are a common congenital anatomic deformity. The ureteral orifice is positioned distal to the bladder trigone within the uterus, vestibule, or vagina. More than 95% of ectopic ureters in affected dogs transverse intramurally and are candidates for the procedure. A laser is used to cut the intramural ectopic tunnel in this endoscopic procedure (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Endoscopic images during cystoscopic-guided laser ablation in a female dog with an intramural ectopic ureter. Guide wire in the ureteral lumen caudal to the trigone of the bladder (A). Laser fiber through the working channel of the endoscope before laser ablation (B). Laser fiber cutting the medial ureteral wall within the urethral lumen (C). The neoureteral orifice after cystoscopic-guided laser ablation (D).

In the author’s practice, more than 80 dogs (male and female) have successfully undergone endoscopic repair of ectopic ureters. This procedure is performed in conjunction with cystoscopy, fluoroscopy, and a diode or holmium: yttrium-aluminum-garnet (YAG) laser. This outpatient procedure is completed at the time of cystoscopic diagnosis of ectopic ureter, reducing the number of anesthesia events. A recent prospective study in the veterinary literature has shown promising results.3

Ureteroscopy

This procedure is possible in dogs that weigh more than 15 kg. It is mainly performed for the evaluation of idiopathic renal hematuria. Ureteroscopy can be difficult to perform through a normal ureteral orifice, as the ureteral opening in a normal dog is less than 2 mm and the smallest ureteroscope is approximately 2.7 mm. Ureteral access is obtained using cystoscopic visualization with fluoroscopy (Figure 5). Preplacement of a ureteral stent may allow the ureter to dilate enough for the ureteroscope to be passed more easily.

Figure 5. Fluoroscopic images during retrograde ureteronephroscopy in a female dog. A rigid endoscope is placed in the urinary bladder (A). A catheter is advanced into the distal ureteral lumen for a retrograde ureteropyelogram. A guide wire (black arrows) is advanced through the ureter and into the renal pelvis, and an open-ended ureteral catheter (white arrowhead) is advanced over the wire (B). A ureteral dilation catheter (arrows) is advanced over the guide wire to ensure endoscopic passage (C). A flexible endoscope (arrows) is passed through the ureter and into the renal pelvis using fluoroscopic and endoscopic guidance (D).

Essential (idiopathic) renal hematuria can occur when a focal area of bleeding occurs in the upper urinary tract. This can result in iron deficiency anemia (long-term), chronic hematuria, and clot formation or calculi formed because of clots, which can cause ureteral colic or signs of lower urinary tract disease.

In humans, angiomas, hemangiomas, and vascular malformations have been noted on ureteroscopy. These abnormalities can be cauterized using the ureteroscope. This procedure has been performed in a small number of dogs in the author’s practice.

A more applicable procedure for essential renal hematuria is sclerotherapy for topical ureteral infusions (Figure 6). This has been performed in veterinary medicine and is most useful when the ureter is too small to allow ureteroscopic access.4

Figure 6. Retrograde ureteropyelogram during sclerotherapy in a female dog with idiopathic renal hematuria in dorsal recumbency during cystoscopy and fluoroscopy.

The procedure is performed with cystoscopic and fluoroscopic guidance in which a cauterizing sclerosing agent is carefully infused into the renal pelvis to stop the bleeding. The success rate is over 75%, and the procedure avoids the need for ureteronephrectomy. Between 25% and 33% of dogs will have bilateral benign renal bleeding with this condition, so nephrectomy should be avoided when possible.

Laser Lithotripsy

This technique involves fragmentation of uroliths intracorporeally, which can be monitored with a flexible or rigid ureteroscope or cystoscope. The holmium:YAG laser has coagulation and cutting properties and causes fragmentation of the stones on contact. The energy, which is focused on the surface of the urolith, is directed using the cystoscope. The process is effective for cystic, ureteral, and urethral calculi of all types (Figure 7) and during PCNL when necessary for problematic nephroliths.

Figure 7. Endoscopic image of a calcium oxalate stone in a female dog during laser lithotripsy.

Percutaneous Cystolithotomy

Percutaneous cystolithotomy uses a rigid and flexible cystoscope and stone retrieval basket to remove stones from the bladder and urethra of male and female cats and dogs. The procedure is performed through a small incision in the abdomen at the level of the bladder apex. A small sheath is then advanced into the bladder lumen to allow for antegrade cystoscopy and stone retrieval with the stone basket. This fast, effective technique is typically performed outpatient and does not require laparoscopy (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Endoscopic images of a dog with numerous calcium oxalate bladder and urethral stones during percutaneous cystolithotomy. Embedded stones within the urethral lumen (A). Stone basket entrapping the stones (B). Stone basket removing the stones (C).

Urethral Stenting for Malignant Obstructions

Malignant obstructions of the urethra can cause dysuria, marked discomfort, and azotemia. Approximately 10% of patients with transitional carcinoma of the prostate and/or urethra have complete obstruction of the urinary tract, and more than 80% have dysuria. Radiation therapy and chemotherapy have been effective in slowing tumor growth, but a complete cure is rare. More aggressive therapy is indicated in cases of obstruction.

Some studies have described the use of transurethral resections, placement of cystostomy tubes, surgical diversionary procedures, and urethral laser procedures. These techniques rarely hold long-term promise, and cost is often a factor. In addition, many are associated with negative outcomes because of the need for manual urine drainage, increased morbidity, urinary frequency, and infection.

A reliable and safe alternative to establish urethral patency is placement of a self-expanding metallic stent by a transurethral approach with fluoroscopy (Figure 9). This outpatient procedure is associated with good-to-excellent palliative outcomes in more than 95% of cases. It has been successful in both dogs and cats; however, approximately 25% of patients will exhibit some urinary incontinence after stent placement.

Figure 9. Fluoroscopic images of a male dog during urethral stent placement for obstructive prostatic carcinoma (asterisk; A). Retrograde cystourethrography shows the obstructive lesion (arrows). A marker catheter is used to measure the urethral lumen diameter for stent sizing. A constrained urethral stent (arrowhead; B) is placed over a guide wire prior to deployment across the obstructive tumor. The deployed urethral stent (arrowheads; C) shows patency of the urethral lumen. There is still some tumor caudal to the stent (asterisk).

Urethral stenting has also been useful in patients with benign urethral strictures, granulomatous or proliferative urethritis, or reflex dyssynergia when traditional therapies have failed.

Transurethral Submucosal Bulking Agent Implantation

Transurethral submucosal bulking agent implantation using urethroscopy is indicated in patients with urethral sphincter mechanism incompetence if medical management has failed, is not tolerated, or is contraindicated. The procedure has a good overall success rate (>80%), but the average rate of maintaining urinary continence following this procedure has been shown to be 68% at 17 months, with potential indication for reinjections necessary thereafter.5 Varying materials have been used with variable success. Owners should be informed that this process can be cost-prohibitive and the benefits can be short-lived.

Looking Forward

Intraarterial Stem Cell Delivery for Chronic Kidney Disease

The use of autologous mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of feline chronic kidney disease (CKD) is being investigated. At the author’s practice, a fully funded, randomized, placebo-controlled study investigating the use of stems cells in feline patients with International Renal Interest Society (IRIS) stage 3 CKD that compares delivery of these cells intravenously and intraarterially to that of a placebo is currently underway.

This study will follow the patients for 3 years and assess systemic signs; blood pressure; glomerular filtration rate; and serum chemistry, ultrasonographic, and radiographic parameters. The same parameters will also be investigated in canine patients with glomerulonephritis/protein-losing nephropathy.

Intraarterial delivery involves placement of a catheter into the renal artery under fluoroscopic guidance via the femoral or carotid artery. This bypasses systemic circulation of the stem cells to ensure delivery directly into the renal capillary bed and allows higher engraftment rates, which have been shown in various animal models. To date, with more than 75 intraarterial treatments having been performed in more than 30 patients, the procedure appears safe. Efficacy is being investigated, but the results are promising.

Conclusion

To date, with more than 75 intraarterial treatments having been performed in more than 30 patients, the procedure appears safe.

Interventional endoscopy provides new alternatives to the treatment of certain conditions that are traditionally difficult to manage and can be considered when minimally invasive palliation is desired or other alternatives are not considered ideal. More treatments using these, or similar, noninvasive, image-guided therapies continue to become available for veterinary patients.

PCNL = percutaneous nephrolithotomy, SUB = subcutaneous ureteral bypass, YAG = yttrium-aluminum-garnet, CKD = chronic kidney disease

Allyson Berent, DVM, DACVIM, is director of interventional endoscopy services at the Animal Medical Center in New York City. She researches minimally invasive diagnostics and therapeutics, including endourology, laser lithotripsy, hepatic and biliary intervention, and intrahepatic portosystemic shunting. Dr. Berent completed a one-year rotating small animal internship at University of Minnesota, an internal medicine residency at University of Pennsylvania, and an interventional radiology and endoscopy fellowship. She earned her DVM from Cornell University.