Chylous Effusion in a Cat

An 11-year-old, castrated, domestic short-haired cat was presented for respiratory distress.

HistoryThe patient was presented to the primary veterinarian in acute respiratory distress. Pleural effusion was noted on imaging, and 220 mL of opaque, milky white fluid (with small lymphocytes on cytology and 3.5 g/dL total protein) was removed via left-side thoracentesis. The top differentials were pyothorax or chylous effusion. The cat was referred to a specialist for further evaluation of suspected chylothorax.

Related Article: Effusion in Cats

Examination & DiagnosticsOn referral two days later, the patient exhibited moderate tachypnea and dyspnea. Auscultation revealed muffled lung sounds, moderate tachycardia, soft heart murmur, and irregular cardiac rhythm. Pleural effusion was confirmed on radiographs, and milky white fluid (250 mL) was removed via an additional thoracentesis (Figure 1).

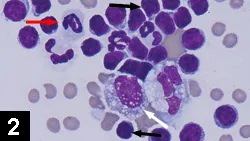

Figure 1. Many small lymphocytes (black arrows), fewer neutrophils (red arrow), and rare vacuolated macrophages (white arrow) were present on cytospin preparation. Erythrocytes were noted in the background. (1000¥ original magnification)

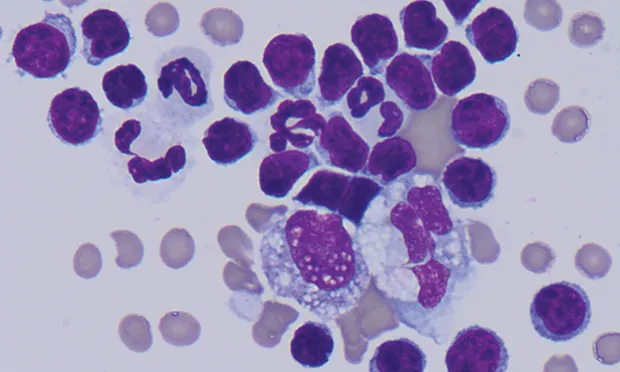

Laboratory AnalysisCBC results showed mild neutrophilia, FIV/FeLV testing was negative, and thyroxine levels were within normal limits. Fluid analysis found markedly higher triglyceride concentration in pleural fluid as compared with serum (see Table, below). On microscopic evaluation, small lymphocytes predominated and lower numbers of vacuolated macrophages and nondegenerate neutrophils were present. The background was light blue to gray and finely vacuolated (Figures 2 & 3).

Figure 2. Many small lymphocytes (black arrows), fewer neutrophils (red arrow), and rare vacuolated macrophages (white arrow) were present on cytospin preparation. Erythrocytes were noted in the background. (1000¥ original magnification)

*Chylous effusions typically have higher TNC counts than do transudates (which usually have TNC counts <1000/μL) and are distinguished from most exudates by predominance of small lymphocytes (Figure 2) and high concentration of triglycerides relative to serum or plasma. Protein concentration was obtained via refractometer.

Ask Yourself:

1. What biochemical test can help distinguish chyle from purulent material?

2. What conditions can cause chylous effusion?

3. What other testing may be warranted?

4. What might interfere with refractometry measurement of protein concentration in the fluid?

Figure 3. Direct smear of the fluid. Fine, faint lipid vacuolation (caused by high triglyceride content) in the background is lost during centrifugation. (1000¥ original magnification)

Diagnosis: Chylous effusion secondary to left-sided heart disease

Neutrophilia and lymphopenia were consistent with a stress (corticosteroid) response. Accumulation of lymphocyte-rich fluid in the pleural space may have also contributed to lymphopenia. In one study, lymphopenia was the most common abnormality noted on routine CBC in cats with chylous effusion.1 In this patient, microscopic and biochemical fluid characteristics were more consistent with chyle than purulent material, despite the presence of inflammatory cells. Chylous effusions often have an inflammatory component. Chyle alone can be an irritant, and the number of neutrophils and macrophages tends to increase with the chronicity of the effusion and (probably) with the frequency of thoracentesis.2 A triglyceride concentration significantly higher in pleural fluid than in a paired serum or plasma sample strongly supports a diagnosis of chylous effusion.3

Related Article: Thoracocentesis

Additional ResultsAn ECG revealed marked hypertrophy of the left ventricle and severe left atrial dilation most consistent with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; atrial premature complexes were also noted, suggesting that the chylous effusion was a manifestation of left-sided congestive heart failure. Cats can develop pleural effusion with left- and right-sided heart failure, as the visceral pleural lymphatics drain into the pulmonary venous circulation.4 In cases of left-sided heart failure, high pressure in the pulmonary venous system can restrict normal thoracic lymphatic drainage.

Chylous EffusionsDietary lipids are repackaged by intestinal epithelium or epithelia into triglyceride-rich chylomicrons. Their large size prevents local uptake by capillaries, and the lipid-rich structures enter the lymphatic system instead. Chylomicron-enriched lymph eventually enters the thoracic duct, which anastomoses with the venous system via lymphaticovenous junction(s) cranial to the heart.5 The high chylomicron content imparts the characteristic opaque, milky white appearance to the fluid, although concurrent hemorrhage can result in pink-tinged effusion (Figure 2); hyporexia or anorexia may result in less opaque fluid with lower triglyceride content. The abundant lipid content of chylous effusions can interfere with light refraction, often rendering refractometric assessment of protein content falsely high.6

Most feline cases are idiopathic.1 When a cause can be identified, there is usually direct disruption of or interference with the thoracic duct or an increase in local venous pressure, impairing adequate lymph drainage or flow. Trauma-induced thoracic duct rupture and mediastinal masses (ie, lymphoma, thymoma, granuloma) reportedly cause chylous effusions.7-10 In addition, heart disease, dirofilariasis, lung lobe torsion, and thrombosis or ligation of the cranial vena cava have been associated with chylous effusions.11-16

Did You Answer?

1. Comparison of triglyceride concentration in fluid and serum or plasma2. Thoracic duct trauma, heart disease (left or right sided), other causes of increased lymphatic pressure or permeability; however, cause is seldom identified3. Echocardiogram, ECG, culture and sensitivity testing of fluid, and heartworm testing4. High lipid content of fluid

SOPHY A. JESTY, DVM, DACVIM (Cardiology, Large Animal), is assistant professor of cardiology at University of Tennessee. She completed a large animal cardiology and ultrasonography fellowship and a residency in large animal internal medicine at University of Pennsylvania’s New Bolton Center before completing a residency in cardiology and a fellowship in cardiac regenerative medicine at Cornell University, where she earned her DVM.

JENNIFER L. SCRUGGS, DVM, PhD, is clinical pathology resident at University of Tennessee and major in the United States Army. She earned a PhD in neuroscience from Vanderbilt University and her DVM from University of Tennessee.

CHYLOUS EFFUSION IN A CAT • Jennifer L. Scruggs, Michael M. Fry, & Sophy A. Jesty

References

1. Chylothorax in cats: 37 cases (1969-1989). Fossum TW, Forrester SD, Swenson CL, et al. JAVMA 198:672-678, 1991.2. Body cavity fluids. Rebar AH, Thompson CA. In Raskin RE, Meyer DJ (eds): Canine and Feline Cytology, A Color Atlas and Interpretation Guide, 2nd ed—St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier, 2010, pp 171-191.3. Cavitary effusions. In Stockham SL, Scott MA (eds): Fundamentals of Veterinary Clinical Pathology, 2nd ed —Ames, IA: Blackwell Publishing, 2008, pp 856-857.4. Pathophysiology and therapy of heart failure. Strickland KN. In Tilley LP, Smith Jr. FWK, Oyama MA, Sleeper MM (eds): Manual of Canine and Feline Cardiology, 4th ed—St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier, 2008, pp 288-314.5. The cisterna chyli and thoracic duct of the cat. Lindsay FEF. J Anat 117:403-412, 1974.6. The usefulness and limitations of hand-held refractometers in veterinary laboratory medicine: An historical and technical review. George JW. Vet Clin Pathol 30:201-210, 2001.

Mechanisms of lymphorrhage into the serous cavities with description of a case. Górecki R, Zajgner J, Wawrze´nczyk B. Pol Med J 11:1242-1251, 1972.8. Diagnosis and treatment of chylothorax associated with lymphoblastic lymphosarcoma in four cats. Forrester SK, Fossum TW, Rogers KS. JAVMA 198:291-294, 1991.9. Thymoma in 11 cats. Carpenter JL, Holzworth J. JAVMA 181:248-251, 1982.

Chylothorax associated with cryptococcal mediastinal granuloma in a cat. Meadows RL, MacWilliams PS, Dzata G, Meinen J. Vet Clin Pathol 22:109-116, 1993.11. Chylothorax associated with right-sided heart failure in five cats. Fossum TW, Miller MW, Rogers KS, et al. JAVMA 204:84-89, 1994.12. Double chambered right ventricle in 9 cats. Koffas H, Fuentes VL, Boswood A, et al. JVIM 21:76-80, 2007.13. Chylothorax subsequent to infection of cats with Dirofilaria immitis. Donahoe JM, Kneller SK, Thompson PE. JAVMA 164:1107-1110, 1974.14. Chylothorax associated with thrombosis of the cranial vena cava. Singh A, Brisson BA. Can Vet J 51:847-852, 2010.15. Chylothorax in the dog and cat: A review. Birchard SJ, McLoughlin MA, Smeak DD. Lymphology 28:64-72, 1995.16. Lung lobe torsion associated with chylothorax in a cat. Mclane MJ, Buote NJ. J Feline Med Surg 13:135-138, 2011.

Suggested Reading

Effusions: Abdominal, thoracic, and pericardial. Rizzi TE, Cowell RL, Tyler RD, Meinkoth JH. In Cowell RL, Tyler RD, Meinkoth JH, DeNicola DB (eds): Diagnostic Cytology and Hematology of the Dog and Cat, 3rd ed—St. Louis: Mosby Elsevier, 2008, pp 235-255.Pathophysiology and therapy of heart failure. Strickland KN. In Tilley LP, Smith Jr. FWK, Oyama MA, Sleeper MM (eds): Manual of Canine and Feline Cardiology, 4th ed—St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier, 2008, pp 288-314.