Chorioretinitis

David. A. Wilkie, DVM, MS, DACVO, Ohio State University

Chorioretinitis, or posterior uveitis, refers to inflammation of the choroid and retina. Because these posterior ophthalmic tissues are so intimately associated, it is difficult to affect 1 without affecting the other, and inflammatory disease of either results in chorioretinitis.

The choroid is the posterior aspect of the uvea or vascular tunic; it contains blood vessels, melanin, and, dorsally, the tapetum. The choroid supplies nutrition and removes waste material from the retina; provides a cooling function, helping to dissipate heat generated by the visual process; and facilitates vision in dim light. To perform these functions, the choroid has a tremendous blood flow, far more than that simply required for oxygenation. Although this ensures the health of the retina, it also results in significant risk to the retina and choroid from vascular abnormalities (eg, hypertension, hyperviscosity, vasculitis), hematogenously disseminated disease (eg, neoplasia, bacteremia, viremia, tick-borne disease, disseminated mycosis, parasitism, algal infection, protozoal infection), and immune disease (eg, uveodermatologic syndrome).<sup1–9sup> Whereas chorioretinitis is most often bilateral, unilateral disease can occur and does not preclude systemic disease.

Examination of the posterior segment of the eye is indicated in animals with vision disturbance, when anterior uveitis is present, in cases of known systemic disease, and in patients with systemic abnormalities of unknown cause as in fever of unknown origin.

Active chorioretinitis is typically an ocular manifestation of a systemic disease with a hematogenous cause. Baseline data should include a complete history, including travel history and vaccination status, as well as a physical examination, CBC, serum chemistry profile, urinalysis, diagnostic testing for relevant infectious diseases, thoracic and abdominal imaging, and cytology.

Given the predilection for chorioretinitis in many systemic diseases, a dilated fundic examination should also be a routine part of the physical examination in animals with fever of unknown origin and when disseminated neoplasia, mycosis, vasculitis, tick-borne diseases, or similar conditions are considered as possible differentials.

The eyes should be examined in a dark room using an indirect, direct, or PanOptic ophthalmoscope.

To examine the posterior aspect of the eye, the pupil must first be dilated using a short-acting mydriatic, such as 1% tropicamide. The eyes should be examined in a dark room using an indirect, direct, or PanOptic ophthalmoscope (WelchAllyn.com). The veterinarian should be familiar with normal posterior segment variations associated with species, coat, eye color, and age of the animal. An accurate fundic examination allows direct, noninvasive visualization of the arteries, venules, capillaries, and central nervous system.

Clinical Signs

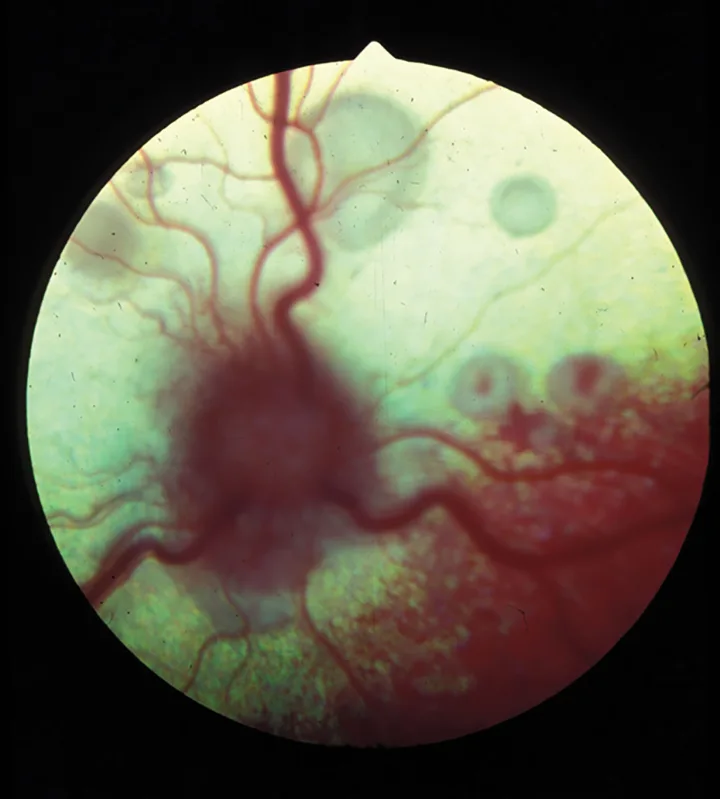

Chorioretinitis appears clinically as a color change or loss of clarity of tissues on fundic examination. With active chorioretinitis, the addition of fluid, protein, and cells within the retina and subretinal tissues will obscure the tapetum or pigment of the choroid (hyporeflective) and may elevate or detach the retina and blur the image. Vascular involvement may result in perivascular cuffing, vasculitis, hemorrhage, and exudate (Figures 1–7). With active chorioretinitis, anterior segment involvement is common, resulting in aqueous flare, miosis, hypopyon, keratic precipitates, cataract, corneal edema, and intraocular pressure (IOP) changes. With chronicity, chorioretinitis leads to focal or diffuse retinal degeneration, tapetal hyperreflectivity, depigmentation, hyperpigmentation, and vascular attenuation (Figures 8–11).

Figure 1.

Active feline chorioretinitis and optic neuritis secondary to systemic cryptococcosis. Multifocal areas of subretinal and peripapillary edema elevate the retina and blur the underlying tapetum.

Treatment

Although treatment of chorioretinitis requires systemic medication, its cause must be identified first. The safest nonspecific treatment option pending diagnosis is administration of systemic nonsteroidal antiinflammatories (NSAIDs) while test results are pending. Systemic corticosteroids should be administered only after infectious causes have been ruled out or are being appropriately treated. If indicated, the dose of systemic corticosteroids may range from antiinflammatory to immunosuppressive, depending on cause. If the cause is immune-mediated, then additional immunosuppressive therapy with azathioprine, cyclosporine, or other similar medications may be required. If there is concurrent anterior uveitis, then topical corticosteroids, NSAIDs, and 1% atropine may also be indicated. With anterior uveitis, determination and monitoring of IOP is also indicated.

The sequelae of chorioretinitis include retinal detachment, retinal degeneration, blindness, phthisis bulbi, cataract, glaucoma, vitreal degeneration, optic nerve atrophy, and loss of the eye.

IOP = intraocular pressure