Canine Pericardial Effusion

Nancy J. Laste, DVM, DACVIM (Cardiology), Bulger Veterinary Hospital, Lawrence, Massachusetts

Profile

Definition

Pericardial effusion is a condition involving an accumulation of fluid within the pericardial sac.

Relatively uncommon

Diffuse regional distribution aside from coccidioidomycosis (infection with Coccidioides immitis), which is regional (southwestern United States)1

Signalment

Pericardial effusion occurs more commonly in large-breed dogs than smaller-breed dogs.2

Breeds at highest risk include golden retrievers, German shepherd dogs, brachycephalic breeds (eg, boxers, bulldogs, pugs), and cocker spaniels.2

According to most studies, there is a male predilection.2,3

Common Causes2

Idiopathic or inflammatory

Secondary to cardiac-associated tumors

Heart-base tumors (chemodectoma, ectopic thyroid carcinoma, other)

Hemangiosarcoma (mainly right atrial)

Secondary to infiltrative or diffuse neoplasia

Mesothelioma

Lymphosarcoma

Infectious

Coccidioidomycosis (regionally prevalent)

See Causes of Canine Pericardial Disease.

Causes of Canine Pericardial Disease

Congenital Pericardial Disease

Partial or total pericardial agenesis

Pericardial cysts

Peritoneopericardial diaphragmatic hernia

Acquired Pericardial Disease/Effusion

Transudative effusions

CHF-associated

Hypoalbuminemia

Uremia

Exudative effusions

Septic pericarditis (bacterial, fungal, protozoal, algal)

Uremia

Hemorrhagic effusions

Coagulopathy

Heart-base tumors

Hemangiosarcoma

Idiopathic pericardial effusion

Left-atrial rupture (secondary to advanced valvular endocardiosis)

Malignant mesothelioma

Primary or metastatic pericardial neoplasia

Trauma

Risk Factors

Mesothelioma

Asbestos exposure has been linked to mesothelioma in humans; early pathology studies suggested a possible connection in dogs, but the link is unsubstantiated.5

Pathophysiology

Pericardial effusion, in the author’s experience, is usually, but not always, associated with cardiac tamponade.

Cardiac tamponade occurs when pericardial pressures exceed right atrial pressures.

Acute cardiac tamponade is an acute fluid accumulation (blood) into the pericardium that causes a rapid increase in pericardial pressure with variable degrees of hemodynamic collapse.

The amount of fluid causing tamponade may be smaller in acute causes.

Chronic cardiac tamponade results from slower accumulations of fluid, often as a result of infiltration and fibrosis of the pericardial sac that leads to decreased distensibility and, eventually, cardiac tamponade.

The slower development of pressure allows more pericardial stretch (often with large volumes of effusion) and time for the development of right-sided congestive heart failure (RCHF), ascites, and pleural effusion.

History

Patients with cardiac tamponade may present with: lethargy, inappetance, exercise intolerance, and acute collapse

Vomiting seems to be common.

Abdominal distention and possibly dyspnea related to RCHF, which suggests a more chronic development of tamponade, may develop.

Physical Examination

Patients vary from bright and responsive to moribund.

Mucous membrane color varies from pink to muddy or pale, often with delayed capillary refill time.

Tachycardia and muffling of heart and/or lung sounds may be present.

Arrhythmias may be present (ventricular arrhythmias are most common).

Femoral pulses are generally weak; some patients exhibit pulsus alternans (varying strength of femoral pulses).

Jugular distention generally present, with or without jugular pulsation.

Dyspnea and muffled lung sounds may be present.

An abdominal fluid wave may be detected.

Clinical Signs

Lethargy, inappetance, exercise intolerance

Dyspnea, collapse

Abdominal distention (not uniformly present)

Vomiting

Diagnosis

Definitive

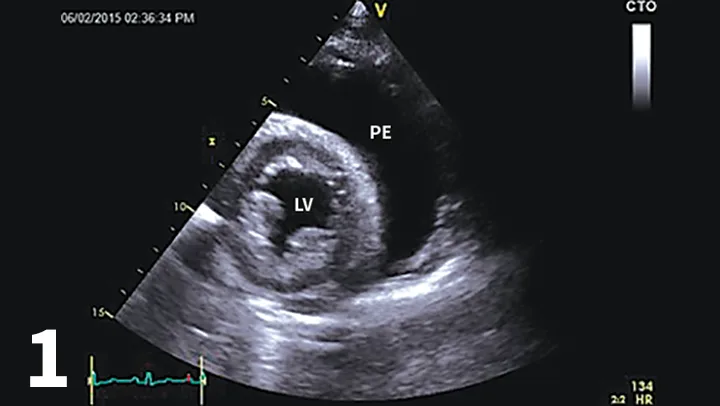

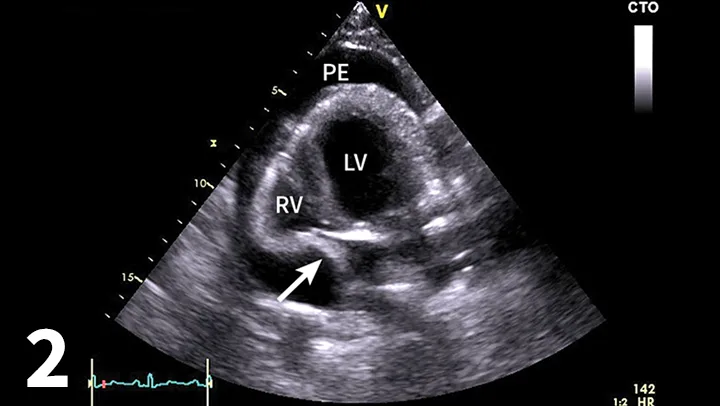

Echocardiography confirms an echo-free space between the heart and the pericardium (Figure 1), may show cardiac tamponade (Figure 2), and may detect mass lesions.

Right parasternal short-axis echocardiogram showing a large accumulation of pericardial effusion. (PE = pericardial effusion, LV = left ventricle)

Four-chamber left apical echocardiographic view showing moderate pericardial effusion with cardiac tamponade. Arrow shows diastolic collapse of the right atrium consistent with cardiac tamponade. (PE = pericardial effusion, LV = left ventricle, RV = right ventricle)

Differentials

Cardiac-associated hemangiosarcoma

Infiltrative pericardial neoplasia

Mesothelioma

Carcinoma

Metastatic neoplasia

Idiopathic pericardial effusion (or benign pericardial effusion)

Heart-base tumors

Chemodectoma

Ectopic thyroid carcinoma

Other tumor type

Peritoneopericardial diaphragmatic hernia (PPDH)

Infectious pericarditis

Coccidioidomycosis (common in the southwest United States)

Lymphosarcoma

Coagulopathy (rodenticide, warfarin toxicity)

Miscellaneous

Uremia-related (rare/theoretical)

Pancreatitis-related (rare/theoretical)

Congestive heart failure (CHF)–related (atypical for dogs); usually low-volume and unlikely to result in cardiac tamponade

Laboratory Findings

No findings are specific for pericardial effusion.

Liver enzyme elevations associated with hepatic congestion may be present.

Increased partial thromboplastin times or activated partial thromboplastin times are found in patients with coagulopathy.

Pericardial fluid analysis

In the author’s clinical experience, most fluid samples of the pericardial effusions are hemorrhagic (and as such, rarely diagnostic).

Serous effusion may be associated with secondary processes based on the author’s clinical experience.

Serosanguinous effusion not consistent with hemangiosarcoma can be seen with mesothelioma, idiopathic pericarditis, or heart-base tumors.

Attempts to use pericardial fluid pH to effectively predict the cause have not been reliable.4

Serum troponin levels: in 1 study, patients with right atrial hemangiosarcoma had higher levels of serum troponin (>0.25 mg/dL) than patients with noncardiac hemangiosarcoma and other causes of pericardial effusion.6

This test may provide additional insight in cases of idiopathic pericardial effusion.6

Mesothelioma is a difficult cytologic diagnosis given that activated mesothelial cells develop as a result of other types of pericardial disease and can appear atypical when not neoplastic.

Right lateral thoracic radiograph for patient presenting with acute collapse. The heart is globoid while the pulmonary vasculature is small. The caudal vena cava is hard to visualize but would likely be dilated.

Imaging

Thoracic radiography

The heart may be relatively normal (acute hemorrhage) or globoid (chronic effusion; Figure 3). Distention of the caudal vena cava, ± pleural effusion, ± peritoneal effusion, may also be present.

Cardiac-associated tumors may be suspected based on atypical cardiac silhouette.

Metastatic lesions may be present (most commonly with cardiac hemangiosarcoma).

When PPDH is suspected, overlap of peritoneum and pericardium will be noted; abdominal viscera may be seen within the pericardium.

PPDH is frequently associated with sternal deformities.

Echocardiography

Survey of the heart base and heart for cardiac-associated tumors.

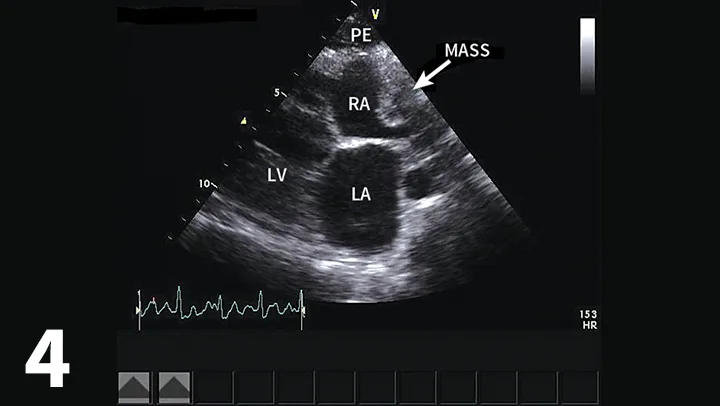

Right atrial masses are most typically hemangiosarcoma (Figure 4).7

Heart-base tumors directly adjacent to the base of the aorta may be chemodectoma, ectopic thyroid carcinoma, or other tumors, including hemangio-sarcoma.7

Echocardiography by an experienced operator is very specific (>99%) with variable sensitivity (74%–82%) depending on the cause.7

Serial echocardiography increases the sensitivity of echocardiography.

Evaluate for the presence of cardiac tamponade (eg, diastolic collapse of the right atrium) (Figure 2).

Evaluate the thickness of the pericardium.

When finding is echo-negative for tumor, the main differential diagnosis is primary pericardial disease (eg, idiopathic pericarditis, mesothelioma) or occult right atrial mass (right auricular masses are not always easy to visualize).

In cases of echo-positive for tumor, small (2-3 cm), well-circumscribed masses adjacent to the aorta are more consistent with chemodectoma. Right heart–associated masses, often irregular, are more typically hemangiosarcoma, but neuroendocrine tumors (eg, thyroid carcinoma, chemodectoma) have been described in this region as well.7

PPDH: tissue within the pericardium (most typically omental fat, hepatic tissue).

Specialized testing

Transesophageal echocardiography may allow visualization of additional occult mass lesions but requires general anesthesia and specialized equipment and is technically challenging.

CT and MRI may reveal additional cardiac-associated tumors but require general anesthesia, significant expense, and specialized equipment.

Right parasternal long-axis echocardiographic view of a dog with a small accumulation of pericardial effusion and an infiltrative right atrial mass (hemangiosarcoma most likely). (PE = pericardial effusion, RA = right atrium, LA = left atrium, LV = left ventricle)

Postmortem Findings

Hemangiosarcoma with hemopericardium may have pulmonary metastatic lesions and/or splenic hemangiosarcoma.

Pericardial tissue is usually normal.

Hemopericardium is evident in heart-base tumors. Pericardial tissue may be slightly fibrotic (chronic fluid accumulation) or may be normal.

Primary pericardial disease

Mesothelioma: Thickening, nodular infiltration of parietal and/or visceral pericardium with neoplastic mesothelial cells. Neoplasia may extend to the pleural space.

Idiopathic pericardial effusion (ie, fibrosing pericarditis): Varying degree of fibrosis and inflammatory infiltrate.

Pericardium is thickened and nonelastic.

There is no evidence of neoplasia.

Treatment

Pericardiocentesis (In-Patient Preferred)

Performed as follows:

Place IV catheter.

Lightly sedate the patient if required.

Administer local anesthesia (2% lidocaine infused at the predicted centesis site).

Position patient in left lateral or sternal recumbency.

Aseptically prepare the site.

The preferred location is the fifth right intercostal space, just below the costochondral junction (at the cardiac notch in the lungs), or as best defined by cardiac ultrasound.

Echocardiographic guidance is optional in most cases but recommended in patients with a low-volume effusion.

For this procedure, a 19-gauge (17-gauge placement needle) or 16-gauge (14-gauge placement needle) through-the-needle catheter is the author’s preferred tool.

For the emergency, 14- or 16-gauge, 6-inch, over-the-needle catheters with additional side holes are frequently used but are more likely to result in incomplete tap or spillage of the effusion into the thorax.

With electrocardiography (ECG) monitoring, advance the needle into the pericardial sac.

There is typically a blood flash-back.

Thread the catheter through the needle.

Once fully threaded, retract the needle from the chest and place the needle guard according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Aggressive ventricular arrhythmias generally suggest contact with the heart; pull back slightly if necessary.

Set aside a fluid sample to observe for clotting.

Clotted blood indicates cardiac or vessel puncture and necessitates needle retraction.

Continue to monitor the ECG throughout the pericardiocentesis.

Collect samples for fluid analysis (EDTA tube, serum tube).

Look for decrease in heart rate, which is consistent with relief of the cardiac tamponade.

Fluid administration may be required depending on patient’s hemodynamic status.

Following the procedure, ideally monitor the ECG for 12 to 24 hours for arrhythmias and for increasing heart rate consistent with possible recurrent cardiac tamponade.

What About Cats?

Primary pericardial disease is rare in cats.8

Pericardial effusion as a manifestation of left-sided heart failure in cats is the most common cause (75% of cases).8 It generally responds to diuretic therapy and does not result in cardiac tamponade.

Lymphosarcoma and mesothelioma are the most common cardiac neoplasms in cats.8

Idiopathic pericardial effusion occurs rarely in cats and involves a large accumulation of a pure transudate; it is often recurrent.

PPDH is more common in cats than dogs and is often an incidental finding.8

Pericardiocentesis is easy to perform on cats using a 23- or 25-gauge butterfly set. Location is optimized using echocardiographic guidance.

Medical

Rarely effective

Anti-inflammatory therapy may be used to avoid fluid recurrence.

Based on the author’s clinical experience, metronomic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy may be used for patients with mesothelioma.

Prednisone in anti-inflammatory doses may be used to treat idiopathic effusions (extrapolated from human practice).

Chemotherapy can be used for neoplastic causes.

Adriamycin may be given for therapy with hemangiosarcoma.9

Toceranib (Palladia, zoetisus.com) therapy is used by oncologists for patients with heart-base masses and hemangiosarcoma in the author’s experience.

Aminocaproic acid (Amicar, amicar.org) may be prescribed for large-breed dogs to reduce tumor bleeding (extrapolation from human medicine).

Surgical

Most commonly performed by specialists

Thoracotomy for subtotal pericardiectomy is the best approach for restrictive pericardial disease or if owners choose to be aggressive with tumor biopsy or resection (right auricular hemangiosarcoma lesions).

Thoracoscopy is used for minimally invasive exploration of the thorax to make a pericardial window.

It is palliative for heart-base masses and hemangiosarcoma (no further episodes of cardiac tamponade); it is potentially curative for idiopathic pericarditis.

Client Education

Pericardial effusion almost always returns unless a pericardial window is made; how and when it returns helps establish likely diagnosis in tumor-negative dogs.

Acute, rapid return is most consistent with acute hemopericardium related to hemangiosarcoma.

Slow, gradual accumulation is more typical with primary pericardial disease (eg, idiopathic, mesothelioma) or a heart-base tumor.

Echocardiogram-negative dogs with first-time pericardial effusion should have pericardiocentesis without additional therapy to avoid spread of pericardial mesothelioma to the pleural space.

In the author’s experience, a substantial percentage of patients diagnosed with idiopathic pericarditis will experience future pleural effusion and subsequent diagnosis of mesothelioma (postpericardectomy or pericardial window). Therefore, this remains on the differential diagnosis list for a minimum of 6 months.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that Yunnan Baiyao is an herbal remedy that may decrease tumor bleeding.

Follow-up

Instruct owners to monitor for signs of recurrent cardiac tamponade.

Perform a recheck echocardiogram 2 weeks post-discharge and periodically thereafter as the client wishes or can afford.

In General

Prognosis

Cardiac tamponade is a medical emergency and is occasionally fatal.

Neoplastic causes associated with variable long-term prognosis.

Patients with cardiac hemangiosarcoma have the poorest prognosis (mean survival time [MST] ranges from 16 days without treatment, 46 days with pericardiectomy and tumor resection, 164 days with pericardiectomy, tumor resection and chemotherapy).3,9

Patients with chemodectoma have a more favorable prognosis but generally experience recurrent effusion.

Overall survival data are less clear because biopsy diagnosis is less commonly made premortem.

In 1 study, (n = 24) dogs with biopsy-Confirmed heart-base masses having pericardiectomy had significantly longer survival (MST = 730 days, 14 dogs with pericardiectomy vs 42 days, 10 dogs without pericardiectomy), regardless of whether they had pericardial effusion at the time of surgery.5

Malignant mesothelioma may be slow and insidious, but patients ultimately develop malignant pleural effusion.

MST is difficult to predict for this disease as diagnosis can be elusive; in 1 study MST was 13.6 months.7

Lymphosarcoma generally responds well to treatment for the systemic disease.10

Idiopathic pericarditis

Patients generally do well, but most require pericardiectomy or pericardial window. (MST = 15.3 months).3

In the author’s clinical experience, a significant percentage of dogs with idiopathic pericarditis are ultimately diagnosed with mesothelioma.

One study suggested significantly better survival after thoracotomy with subtotal pericardiectomy than thorascopic pericardial window,11 although this is still controversial.

CHF = congestive heart failure, ECG = echocardiogram, MST = mean survival time, PPDH = peritoneopericardial diaphragmatic hernia, RCHF = right-sided congestive heart failure