Canine Leishmaniasis: An Overview

Lluis Ferrer, LV, PhD, DECVD, Tufts University Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine

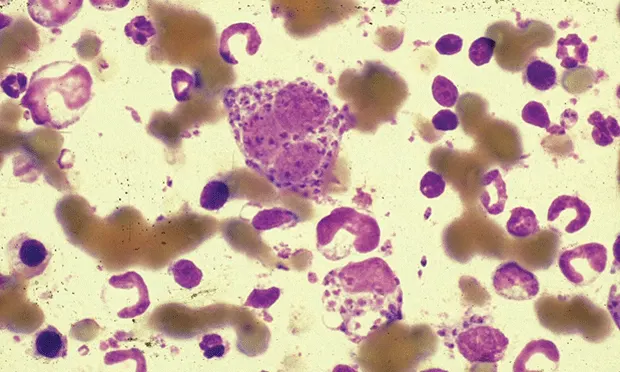

Figure 1 (above). Cytology stain of bone marrow smear showing Leishmania spp in a dog.

Profile

Canine leishmaniasis is a serious zoonotic disease caused by the protozoan parasite Leishmania infantum (syn, L chagasi), dogs are the main reservoir.

Disease manifestation is complex. When a dog becomes infected, progression to disease depends on several factors, particularly genetic background and immune response.

It is thus important to distinguish asymptomatic infected dogs from infected dogs with disease signs.

In susceptible animals, infection can spread to many areas (eg, skin, lymphatic and hematopoietic organs).

In advanced stages, various organs and systems (eg, kidneys, liver, eyes, joints, GI tract) can be affected.

Multisystem complexity can create diagnostic and therapeutic challenges.

Related Article: Companion Animals & One Health

Geographic Distribution

Canine leishmaniasis is endemic in Asia, southern Europe, northern Africa, and Central and South America.1

Data suggest it is expanding.2

The United States was once considered free of the disease, but an outbreak was identified in foxhounds in 1999, and canine leishmaniasis has now been reported in many states.

Vector-borne transmission has not been demonstrated in the United States, where vertical transmission seems likely.

Leishmaniasis is occasionally seen in nonendemic countries in dogs that had visited endemic areas.

Prevalence

In endemic areas, prevalence of infection can be ≥50% with seroprevalence rates around 20%, although prevalence of clinical disease is lower (usually 1%–5%).3

Prevalence in at-risk breeds in the United States is thought to be around 5%, with increased pockets of infection and seroprevalence within certain kennels.4

Signalment

The disease affects all breeds and ages, and both sexes.

Certain breeds (eg, German shepherd dog, boxer, rottweiler) are predisposed.

Some Mediterranean breeds (eg, Ibizan hound) appear somewhat resistant.

In the United States, the disease is seen primarily in dogs with travel history or breeds originating from endemic areas (eg, Corsica, foxhound, Italian spinone, Neapolitan mastiff, briard).

Signs peak in 2 age groups: young (1–4 years) and older (>7 years).

The first group likely corresponds to dogs that are genetically predisposed or naïve immunosuppressed (from malnutrition or previous infection with other pathogens).

The second is likely associated with disease comorbidities or immune senescence.

Related Article:Lick Granuloma: What's the Underlying Cause

Figure 2. Phlebotomine sand fly, a vector for Leishmania spp transmission

Causes & Risks

In some areas, L infantum completes its life cycle in 2 hosts:

A phlebotomine sand fly vector, which transmits the flagellated extracellular promastigote form

Mammals, in which the intracellular amastigote form develops

Risk for infection is greater at dusk and in late evening (ie, when sand flies are most active).

Non–sand fly transmission has been described, but its role in natural history and epidemiology of leishmaniasis remains unclear.

Proven modes include infection through transfused blood products from carrier blood donors, vertical transmission, and venereal transmission.

Recent data have demonstrated vertical transmission of the parasite in foxhounds naturally infected in the United States.2

Pathophysiology

The immune response plays a key role in the progression of Leishmania spp infection.

In many dogs, an effective cellular immune response (T-helper-1 driven) can lead to infection control and absence of signs (resistant dogs).

By contrast, dogs developing humoral immune response (T-helper-2 driven) produce high amounts of antibodies ineffective at controlling infection; these dogs develop signs and lesions.

In these animals, the main pathomechanisms result from multisystemic granulomatous inflammation and immune complex–mediated lesions (glomerulonephritis, uveitis, arthritis, vasculitis).

Diagnosis

History

In endemic areas, lifestyle (outdoors) is important.

In nonendemic areas, detailed travel and breed history and origin are important.

A history of chronic lymphocytosis is common in many leishmaniasis cases.

Physical Examination

A complete examination should be performed in suspected dogs, with special attention to the lymphoid organs, skin and mucous membranes, and eyes (ophthalmologic examination is recommended).

Affected dogs present with a combination of general, cutaneous, ocular, and other common signs.

General

Lethargy

Change in appetite

Weight loss (cachexia and muscle atrophy in advanced cases)

Generalized lymphadenomegaly

Splenomegaly

Polyuria and polydipsia

Vomiting and diarrhea

Figure 3. Characteristic exfoliative dermatitis and alopecia in a dog with leishmaniasis

Cutaneous

Nonpruritic exfoliative dermatitis ± alopecia

Erosive-ulcerative dermatitis mostly at mucocutaneous junctions

Nodular or papular dermatitis

Pustular dermatitis

Onychogryphosis

Figure 4A. German shepherd dog with leishmaniasis

Figure 4B. ulcerative lesions were present on the limbs

Ocular

Keratoconjunctivitis (common or sicca)

Blepharitis

Anterior uveitis/endophthalmitis

Other

Lameness (erosive or nonerosive polyarthritis, osteomyelitis)

Epistaxis

Mucosal lesions (oral, genital)

Myositis and polymyositis, atrophic masticatory myositis

Cutaneous and systemic vasculitis

Definitive Diagnosis

Diagnosis of canine leishmaniasis is based on characteristic signs, clinicopathologic abnormalities, and/or clearly positive serology (IFA test, ELISA).3

Serology is preferred because antibody titers generally correlate to severity.

Identification of amastigotes in cytology or histologic samples from lesional tissues is also diagnostic.

Other Diagnostics

PCR detection of Leishmania spp DNA in tissue samples allows sensitive and specific diagnosis of infection.

PCR testing can be performed on DNA-extracted blood, tissue, or histopathologic specimens.

Assays based on detection of kinetoplast DNA (kDNA) appear to be most sensitive for direct detection in infected tissues.

PCR techniques are especially valuable in nonendemic countries, as otherwise there is no evidence of parasite presence.

Real-time PCR testing allows quantification of Leishmania spp in tissue samples from infected dogs, which is important for diagnosis and follow-up.

Increased parasitic load is usually associated with more severe signs.

Information provided by PCR test results should not be separated from data obtained from clinicopathologic and serologic evaluations.

Infection without disease is common in endemic areas.

Canine leishmaniasis commonly appears to be associated with (or a consequence of) another disease.

Any sign or clinicopathologic abnormality should be investigated.

Clinical leishmaniasis in older dogs living in endemic regions for years but without clinical signs merits more detailed investigation.

Differential Diagnosis

Considering the diverse signs, diagnostic differentials can vary greatly.

Canine leishmaniasis can mimic almost any canine disease and should be on the differentials list when diffuse crusting dermatosis is detected along with weight loss or asthenia.

For foxhounds, foxhound mixed breeds, or dogs that live or have lived in an endemic area, leishmaniasis should be higher on the differentials list.

Leishmaniasis should also be considered in dogs with splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, muscle wasting, facial alopecia, swollen and painful joints, lymphadenomegaly, anterior uveitis, blepharedema and blepharitis, kerato-conjunctivitis, panophthalmitis, polyuria, polydipsia, polyphagia, epistaxis, melena, or diarrhea.4

Laboratory Findings & Imaging

CBC: Mild to moderate nonregenerative anemia, leukocytosis or leukopenia, thrombocytopathy, thrombocytopenia

Serum biochemistry profile: Renal azotemia, elevated liver enzymes, C-reactive protein, and other acute-phase proteins

Protein electrophoresis: Polyclonal beta- and/or gamma-globulinemia, hypoalbuminemia, decreased albumin:globulin ratio

Impaired secondary hemostasis and fibrinolysis

Urinalysis: Mild to severe proteinuria

Lymph node cytology: Consistent with lymphoid hyperplasia; presence of Leishmania spp amastigotes in 30% of cases

Bone marrow cytology: Reactive; presence of Leishmania amastigotes in 30%–50% of cases

Abdominal ultrasonography: Usually detects splenomegaly and occasionally hepatomegaly

Treatment

Most cases are outpatient.

Renal disease requires hospitalization and fluid therapy for supportive care.

Medications

A combination of antimonials (meglumine antimoniate) or miltefosine with allopurinol is the therapy of choice.1

These drugs may not be available in some countries.

In the United States, they can be obtained through the Centers for Disease Control.

Antimonials or miltefosine are usually administered for 4 weeks and allopurinol for a minimum of 6 months.

In mild cases or seropositive dogs without signs, domperidone has demonstrated efficacy in disease control.

Proteinuria, if present, can be treated with ACE inhibitors (eg, benazepril).

Ocular lesions (keratoconjunctivitis, uveitis) require specific treatment.

Meglumine Antimoniate

Parasiticidal drug

Recommended at 100 mg/kg q24h SC for 4 weeks

In relapses, repeat dosage

Adverse effects include lethargy and pain at inoculation site.

Miltefosine

Alkylphospholipid; toxic to Leishmania spp parasites

Recommended at 2 mg/kg q24h PO for 4 weeks

In relapses, repeat dosage

May cause vomiting

Allopurinol

Parasitostatic drug

Prescribed in combination with one of the previous drugs at 10 mg/kg q24h; not to exceed 600 mg/day

May cause potentially severe xanthine urolithiasis

Urinalysis should be performed regularly.

Cannot be administered with azathioprine because of drug interaction

Domperidone

Immunomodulating/potentiating drug

Administered at 0.5 mg/kg q24h for 1 month

Treatment can be repeated q3–4mo to prevent relapse.

Nutritional Aspects

A high-quality diet helps the immune system control infection and clinical signs.

Client Education

Dog owners should be informed that canine leishmaniasis is zoonotic and dogs are the main reservoir.

Direct transmission from infected dog to human is extremely rare.

In the United States, although autochthonous cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis have been reported, there have been no autochthonous cases of visceral leishmaniasis in humans.4Owners should be informed that leishmaniasis is chronic and requires lengthy treatment and lifelong follow-up.

Dogs must be adequately treated for ecto- and endoparasites.

Contraindications

Renal disease should be treated before beginning specific Leishmania spp treatment (antimonials or miltefosine)

Follow-up

Patient Monitoring

Patients should be evaluated after 1, 3, and 6 months of treatment and then q6mo for life.

Evaluation should include thorough examination, CBC, serum biochemistry profile, urinalysis, and serology (q6mo).

Real-time PCR testing can help identify relapse (high parasitic load in sample).

Prognosis

Prognosis is often guarded.

Prognosis is poor in dogs with severe renal disease.

Prevention

Topical insecticides, such as a deltamethrin-impregnated collar (q5mo) or spot-on permethrins (q3wk) have shown >90% protection and, when used extensively, can lower disease prevalence.5

Use of insecticides in ill dogs is recommended to prevent transmission.

Three protein vaccines with a saponin as a coadjuvant are available (1 in Europe, 2 in Brazil).

Considered safe, these vaccines confer high, although incomplete, protection (~90%, with a vaccine efficacy of 70%–80%).

Annual vaccination is required to maintain immunity.

Vaccine reaction rates are high, particularly in small dogs.

Recent data suggest that regular use of domperidone can be preventive, although large controlled studies are pending.

In General

Relative Cost

Relative cost for diagnosis and treatment: $$$$

Future Considerations

Canine leishmaniasis research is ongoing, with new vaccines and drugs expected to reach the market in the next few years.