Canine Heartworm Infection

Profile

Definition

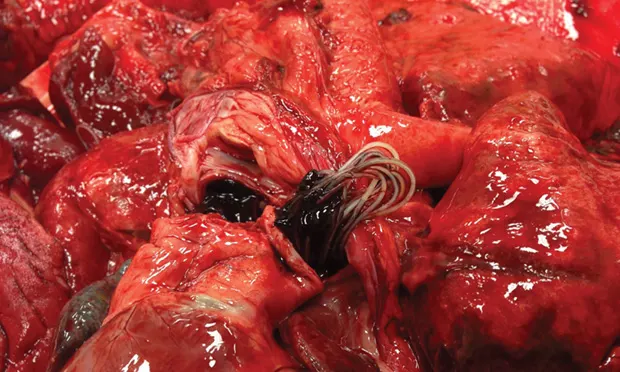

Disease of the pulmonary vasculature caused by the parasite Dirofilaria immitis (Figure 1, above)

Figure. Gross photo of Dirofilaria immitis in the pulmonary artery of a dog. Courtesy Dr. Julia A. Conway

Geographic Distribution

D immitis is found in all 50 states, with increased prevalence in warmer climates.

Transmission

Mosquitoes extract the L1 microfilarial stage of D immitis from an infected dog.

L1-L3 molting occurs within the mosquito.

The L3 larval stage enters the bloodstream of another dog when the mosquito bites.

L3-L5 (adult) molting occurs within the dog.

Related Article: Feline Heartworm Infection

Risk Factors

Any dog that does not receive preventive medication is at risk for heartworm disease.

In endemic areas, up to 45% of dogs that do not receive preventive medication can be expected to have heartworm disease.1

Pathophysiology

Adult heartworms lodge in the pulmonary artery and reproduce.

The direct endothelial contact of adult worms induces an inflammatory response (ie, arteritis) that causes endothelial thickening.

The degree of host immune response directly influences the extent of the disease process.

Blood flow obstruction (by the presence of worms) and endothelial thickening can lead to pulmonary hypertension and fibrosis.

Antigen–antibody complexes can cause microvascular and glomerular damage.

Embolism of dead worm fragments and fibrin clots can lead to hypoxemia.

Larger worm burdens can cause caval syndrome.

Worms back up into the right ventricle and atrium and become entangled in the tricuspid apparatus.

Shear force of RBCs against the worms creates intravascular hemolysis, hemoglobinemia, and hemoglobinuria.

Volume overload because of tricuspid and/or pulmonary insufficiency and right ventricular systolic dysfunction can lead to signs of right-sided heart failure.

Volume underload of the left side of the heart can cause hypovolemia and shock.

Related Article: Canine Heartworm Therapy

Clinical Signs

Many dogs with D immitis infection have no signs, but cough, exercise intolerance, and lethargy may be seen.

Caval syndrome is the most severe form of heartworm disease.

Patients may present with pale mucous membranes, pronounced right-sided heart murmur, shock, hemoglobinuria, hemoglobinemia, and jugular pulsations.

Sudden death may occur.

Diagnosis

Laboratory Findings

Serum chemistry panel is often within reference ranges.

In more severe cases, increased liver enzyme activity may be present because of hepatic congestion from right-sided heart failure.

Caval syndrome

Azotemia

Hemoglobinemia

Hemoglobinuria

CBC may show eosinophilia.

Related Article: Canine Heartworm Disease

Imaging

Radiography

Enlarged right side of heart (reverse-D appearance on VD view)

Prominent main pulmonary artery bulge

Blunted, tortuous vessels are noted most often in the caudal lung lobes.

Dorsoventral projection is best for evaluation of pulmonary vasculature.

Echocardiography

In general, abnormal findings will not be noted with uncomplicated heartworm disease.

Right ventricular dilation or hypertrophy and tricuspid or pulmonic valve insufficiency may be present with more severe disease.

Worms may be visualized in the pulmonary arteries, but quantification of worm burden is difficult.

Echocardiography results may provide good confirmation for caval syndrome.

Worms can be visualized in the right atrium/right ventricle.

Additional Diagnostics

Antibody testing is not often performed.

Antigen testing is preferred.

Tests for the presence of mature adult female worms; heartworm larvae must have been present 6 months for a positive test result.

The test is very sensitive and nearly 100% specific.

Microfilariae testing is confirmatory, but differentiation from microfilariae of Acanthocheilonema reconditum (formerly Dipetalonema reconditum) is important.

Confirms that the dog is contagious via mosquito vector

Negative results may occur if a dog receives macrocyclic lactone preventive medication.

Helps predict protocol for possible adverse reaction to treatment

Related Article: Treating Canine Heartworm Infection

Treatment

To determine severity of disease and help predict therapy response and potential posttreatment complications, pretreatment evaluation (ie, staging) should be performed.

Thoracic radiography (2 lateral views and 1 DV view)

CBC and serum chemistry panel to evaluate for underlying systemic disease and ensure patient is healthy enough for adulticide therapy

Urinalysis to evaluate for proteinuria and bilirubinuria

Confirmatory heartworm test (eg, microfilariae or repeat antigen testing)

Thorough physical examination

History, including time patient was without heartworm prevention, prevalence, and severity of clinical signs at home

Adulticide Therapy

Melarsomine dihydrochloride (Immiticide, merial.com) is approved for use by the FDA.

Treatment with macrocyclic lactone immediately following diagnosis may decrease or eliminate microfilariae and eliminate L3 and early L4 larval stages.2

These stages are not proven to be eliminated by melarsomine dihydrochloride.

Adjunct Therapy

Doxycycline is used to eliminate Wolbachia pipientis, a symbiotic bacterium harbored by D immitis.3

Doxycycline is often difficult and/or expensive to obtain; minocycline is a common replacement.

This therapy weakens adult worms and makes them less fertile.

Doxycycline may improve pulmonary pathology, as Wolbachia spp have been shown to contribute to pulmonary inflammation.3

Corticosteroids are often recommended if the dog shows clinical signs (eg, coughing).

Diphenhydramine can be administered before melarsomine administration.

Alternative Therapy

A slow-kill method of placing a dog on macrocyclic lactone and/or doxycycline and waiting for worms to die is not recommended.1

The potential exists for irreversible heart damage while waiting up to 5 years for all worms to die.

Risk for thromboembolism exists until all worms have died and are absorbed.

It selects for macrocyclic lactone resistance.

Client Education

Strict cage rest throughout the duration of treatment is crucial to prevent life-threatening pulmonary embolism caused by dead worms.

Gradual return to activity can take place 6–8 weeks after final administration of melarsomine.

Medications

Melarsomine

2.5 mg/kg via deep lumbar epaxial IM injection

After 1 month, 2 additional injections should be administered 24 hours apart.

Adverse effects include pain at injection site, lethargy, and allergic reaction.

If the patient is not receiving corticosteroids, discomfort can be alleviated with NSAIDs for several days following injection.

Doxycycline

10 mg/kg q12h for 3 weeks starting at time of diagnosis

Minocycline can be used at the same dose if doxycycline is unavailable.

Macrocyclic Lactone

Preventive medications can be started at diagnosis and continued for life.

Prednisolone

Often used to decrease pulmonary inflammation in patients with clinical signs

1–2 mg/kg q12h

Diphenhydramine

Often used to help prevent or decrease allergic reactions associated with adulticide therapy

Should be used before administration of melarsomine therapy

2.2 mg/kg PO or parenterally 1–2 hours before melarsomine injection

Follow-up

All adult heartworms should be eliminated within 1–2 months of final melarsomine injection.

Six months after completion of melarsomine therapy, results of antigen testing should be negative.

If results are positive, adult infection is most likely still present, and adulticide therapy should be restarted.

Testing may also be performed after 6 additional months to determine whether all worms have died.

In General

Prognosis

Prognosis is good to excellent with treatment.

If untreated, prognosis is variable.

Relative Cost

Depending on size of dog and relative cost for melarsomine therapy and associated medication: $$–$$$

Heartworm disease staging: $$–$$$

Relative cost for preventive medication, yearly: $$

Prevention

Heartworm disease is preventable with administration of macrocyclic lactones (see Heartworm Prevention Options for Dogs).

Monthly oral

Ivermectin

Milbemycin oxime

Monthly topical

Selamectin

Moxidectin

6-Month injectable

Moxidectin

Prevention should be started at 8 weeks of age and continued for life.

These medications also have efficacy against some internal and external parasites.

Read the companion article, Feline Heartworm Infection.

WENDY MANDESE, DVM, is a clinical assistant professor in the department of primary care and dentistry at University of Florida, where she also earned her DVM. Prior, she was involved for 11 years in general practices located in Orlando and Gainesville.

AMARA ESTRADA, DVM, DACVIM (Cardiology), is associate professor and associate chair in the department of small animal clinical sciences at University of Florida. Dr. Estrada’s interests include electrophysiology, pacing therapy, complex arrhythmias, cardiac interventional therapy, and cardiac stem cell therapy. She has contributed to numerous research and clinical publications on emergency and critical care medicine and is associate editor of Journal of Veterinary Cardiology. Dr. Estrada earned her DVM from University of Florida before completing an internship at University of Tennessee and residency in cardiology at Cornell University.